English football was on the ropes in the mid-1980s after coming under constant attack by the disease of hooliganism. The distressing events in what was a little-known Belgian stadium 25 years ago this evening inflicted a devastating blow on what had come to be known as the beautiful game. Heysel Stadium in Brussels, hopelessly ill-equipped to host a match as big as the European Cup final involving clubs with the massive fan bases of Liverpool and Juventus, was turned into blood-stained battlefield on which 39 unsuspecting spectators, 32 of them Italians, died.

Liverpool's travelling army of supporters were undoubtedly responsible for causing one of the biggest tragedies in sporting history. Their conduct that night contributed to them, misguidedly, being similarly blamed for the Hillsborough disaster four years later at which 96 of their own perished at an FA Cup semi-final against Nottingham Forest. "Revenge" was the word uppermost in the minds of many of the Merseysiders who had travelled to the Belgian capital for their team's fourth European Cup final appearance in five years.

Twelve months earlier when winning the trophy for the fourth time in eight seasons, they found themselves facing what was effectively an away match against AC Roma in the Italian capital's Olympic Stadium. Their heavily outnumbered fans came off worse in a succession of skirmishes before, during and after the match, which was decided in their favour through a penalty shoot-out. But none of them died.

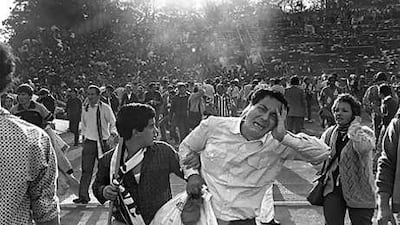

Those seeking retribution set out to "even the score" with Italian adversaries, not kill them. But kill them they did when they broke through a thin dividing barrier and chased fleeing Juventus fans into a wall that collapsed under the weight of the terrified hordes clambering over it. The carnage, ludicrously, failed to prevent the match from going ahead and it eventually went Juve's way courtesy of a dubious penalty award which allowed Michel Platini, the legendary French forward who is now president of Uefa, to assume the hollow role of match-winner.

It was decreed as bodies were being carried to a makeshift mortuary on stretchers made out of advertising hoardings that it was the safest policy to make a delayed start to the showpiece fixture, rather than take the sensible and respectful option of abandoning it. That was the last time an English club side would be seen in Europe for five years, closing a glorious chapter for the country on the field of play and a shameful period off the field.

Margaret Thatcher, the prime minister at the time, immediately urged the English Football Association to withdraw English clubs from the following season's European tournaments. Before the FA could respond to that demand, Uefa had made the decision for them by imposing a blanket indefinite ban. Ironically, the biggest sufferers during the five years of exile were Liverpool's closest neighbours Everton, who had established themselves as the finest team in England by winning the League Championship and European Cup Winners' Cup as well as reaching the FA Cup final that season.

Everton, who also won their domestic title in 1987, would have fancied their chances of emulating Nottingham Forest and Aston Villa in following Manchester United and Liverpool to the pinnacle of European football. Instead, they went into a period of decline as clubs of their status struggled to attract and retain top-class players who wanted to play in Europe. Fourteen years went by after Liverpool's ill-fated night at Heysel until Manchester United became the next English team to reach the final which by then had become the Champions League.

Liverpool themselves returned to the European summit in 2005 by overcoming more Italian opposition in the shape of AC Milan in a thrilling final. On the way to that Istanbul showpiece, the Merseysiders were drawn against Juventus for the first time since Heysel. Turin visitors were greeted to Anfield by Liverpool fans holding aloft placards bearing the message "Amicizia" - the Italian word for "friendship". Some Juventus supporters applauded; others turned their backs.

The scars were healing on the field for Liverpool but not off it. wjohnson@thenational.ae