Donald Trump came to office vowing to end what he saw as China’s free ride on trade and security issues, which has allowed it to flex its muscles more strongly than ever. But there is little sign that the new American president’s China approach is different to that of his predecessor, Barack Obama, on whose watch Beijing initiated coercive actions with impunity in the South and East China Seas.

For example, to tackle North Korea, Mr Trump (like Mr Obama) has sought the help of China. As the White House stated on March 20, it wants China to “step in and play a larger role” on the North Korean issue. But the previous two US administrations also relied on sanctions and Beijing to tame North Korea, only to see that reclusive nation significantly advance its nuclear and missile capabilities.

A greater US reliance on China is unlikely to salvage a failed North Korea policy but will almost certainly result in Beijing exacting a stiff price from the Trump administration, including in relation to the South China Sea. Beijing has already savoured success in scuttling Mr Trump’s effort to modify America’s long-standing “one China” policy.Secretary of state Rex Tillerson’s recent visit to Beijing suggested that the US is willing to bend over backward to curry favour with China. Instead of delivering a clear message, Mr Tillerson mouthed catchphrases such as “win-win” and “mutual respect” that are code for the US accommodating China’s core interests and accepting a new model of bilateral ties.

It was music to Chinese ears as Mr Tillerson echoed the phrase “win-win” cooperation, because it is a phrase that Chinese analysts impishly refer to as entailing a double win for China. For Beijing, the tag “mutual respect” holds great strategic importance: it is taken to mean that the United States and China would band together (in a sort of G2) to manage international problems by respecting each other’s “core interests”. This, in turn, implies that the US would avoid challenging China on the Taiwan and Tibet issues and in Beijing’s new “core-interest” area, the South China Sea.

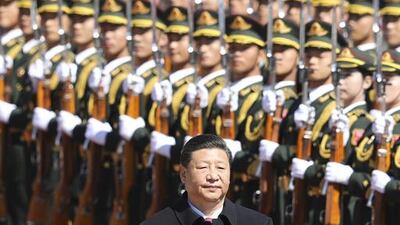

Mr Tillerson articulated the catchphrases by parroting Chinese president Xi Jinping’s words. For example, Mr Xi said in November 2014 during a joint news conference with Mr Obama in Beijing that “China is ready to work with the United States to make efforts in a number of priority areas and putting into effect such principles as non-confrontation, non-conflict, mutual respect and win-win cooperation”. Mr Tillerson repeated the exact same principles twice in Beijing – in his opening remarks at a March 18 news conference with Chinese foreign minister Wang Yi and later that day at the start of talks with Mr Wang. Mr Tillerson’s words were splashed all over the official Chinese media.The Trump administration’s muddled China policy has made it harder to secure meaningful results in negotiations with Beijing on security and trade issues.

Mr Tillerson personifies the confusion. During his confirmation process, he implicitly criticised Mr Obama’s pussyfooting on China by describing Chinese expansion in the South China Sea as “akin to Russia’s taking Crimea” from Ukraine. He first said that the US should “send China a clear signal” by blocking its access to the seven artificial islands it has built, but later backed away by saying that the US ought only to be “capable” of restricting such access in the event of a contingency.

Now, as the US courts greater Chinese cooperation on North Korea and prepares to welcome Mr Xi as a visitor next month, a clearer American stance against China’s territorial revisionism in Asia has become uncertain. In fact, there is talk in Washington that the Trump administration has little choice but to accept that China’s territorial gains in the South China Sea cannot be rolled back.

Such acceptance, however tacit, is likely to hold security implications for America’s allies and security partners in Asia, because it will embolden Chinese revisionism in other regions – from the East China Sea to the Himalayas – while allowing China to consolidate its penetration and influence in the South China Sea. After deploying anti-aircraft and other short-range weapons systems on all its man-made islands in the South China Sea, Beijing is now building structures on three of them to place longer range surface-to-air missiles.

In recent years, the US has made the most of Asian concerns over China’s increasingly muscular approach by strengthening military ties with allies in Asia and forging security relationships with new friends. However, there has been little credible American pushback against China’s violation of international law in changing the status quo or against its strategy to create a Sinosphere of client nations through the geopolitically far-reaching “one belt, one road” initiative.

Mr Trump’s ascension to power appeared to greatly threaten China’s interests. But China thus far has not only escaped any punitive American counteraction on trade and security matters, but also the expected Trump-Xi bonhomie next month at Mar-a-Lago could advertise that the more things change, the more they stay the same in US foreign policy. Besieged by allegations of collusion between his campaign associates and Russia, Mr Trump has – to Beijing’s relief – found little space to focus attention on revamping his predecessor’s China policy.

Brahma Chellaney is an author and professor