weekend eye

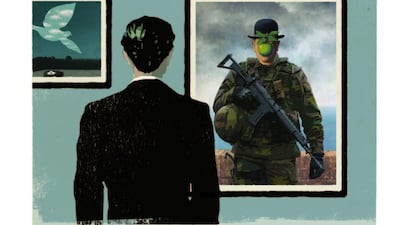

Like a 21st-century reinterpretation of Belgian surrealist René Magritte’s famous Golconda, the sky over Brussels has been raining heavily armed soldiers and armoured personnel carriers, instead of the bowler-hatted gentlemen wearing raincoats in the original.

Though a familiar sight in cities undergoing a revolution, coup or popular uprising, images of the laid-back city of cosy cafes which I called home for many years under lockdown seemed too surreal to fathom – and an overreaction of mega-proportions.

This past week, the mood in the immigrant quarters of the capital was sombre. Already outraged by the Paris attacks, which were partially linked to the Brussels neighbourhood of Molenbeek, described in the media as a “hotbed of extremism” and “jihad central”, Moroccans and other Muslims feel a mix of anxiety and fear.

“They are afraid of how society sees them,” describes Maher Hamoud, an Egyptian journalist and academic currently based in Brussels. Many fear a backlash. “It’s like I can’t do anything any more without feeling unsafe,” admits Kaoutar Bergallou, 16, who studies audiovisual arts in Anderlecht, a neighbourhood with large pockets of poverty and deprivation.

Meanwhile, many native Belgians also feel unsafe and threatened by the Muslim “other” in their midst. “We mustn’t just talk about the problems, but the causes of these problems,” asserts Hassan Al Hilou, 16, an Iraqi-Belgian student and entrepreneur who has started up an online platform for youth.

A growing proportion of Belgians are succumbing to the simplistic narrative that Islam(ism) is at the root of all evil. While Islam, like other religions, can be abused for violent, inhumane ends, this myopic assessment misses the vital issue of what draws young people to such cults in the first place.

Although each radical is driven towards radicalisation by a peculiar, complex set of motives, I am convinced that socio-economic and political marginalisation are major factors.

In many ways, radicals in Brussels are more a product of the local language war, which has hollowed out the state and turned it into a slow and reactive beast, than they are of global holy war.

The frontline of this conflict is Brussels, with its shocking inequalities. The presence of the EU, Nato and the daily arrival of tens of thousands of commuting professionals and civil servants, make the capital the third-richest region in Europe, per-capita.

However, the inner city has suffered enormously from the decades-old conflict between Flemings and Walloons, which has geared the country’s political machinery along ethno-nationalist lines and focused politics on the rivalry between these two communities to the detriment of everything else, including the needs of minorities. The devolution of power to the provinces and the exodus of the well-off to the suburbs and other towns has only amplified the problem for Brussels.

This means that though Brussels generates a huge proportion of Belgium’s GDP, little of that wealth stays in the capital. Today, the city has the highest unemployment rate in the country and one of the highest in Europe. Poverty is rampant and marginalisation rife. “There are young people who have lost hope,” observes Al Hilou.

Some cite examples of jihadists and terrorists who were from middle-class backgrounds or had no money troubles. For instance, they point to Paris attacks suspect and fugitive Salah Abdesalam, who used to run a bar with his brother.

But this misses the point. It is about social, not just economic, marginalisation and exclusion, not to mention aspirations to actual, not just notional, equality. Abdesalam was reportedly raised in Molenbeek, where youth grow up with the idea that either they will be unemployed or need to find a technical vocation to pay the bills. They also have to contend with discrimination and racism from mainstream society, not to mention the demonisation of their cultural heritage.

This may partly explain – though does not excuse – why Abdesalam turned to crime long before he considered terrorism. Social exclusion and growing contempt towards his community, not religious conviction, may also partly explain – but not excuse or justify – how a young man enamoured of drugs and alcohol abandoned his hedonism to pursue violent Islamist terrorism.

The media can raise awareness of these issues and politicians can strike at the root causes. However, despite exceptions, both seem to be generally failing in this mission. “The media frenzy and the politicians are just dirtying Brussels’ reputation,” opined Zouhair Ziani, 16, from Molenbeek, who is also studying audiovisual art.

Social and community workers are also frustrated by this simplistic, binary narrative. “What bothers me and makes me despondent is all the whining about the left-wing ‘politically correct elite’,” complains Eric Gijssen, a video artist and social worker who works with marginalised youth. “But from what I can see Islam-bashing is the new ‘political correctness’.”

The vilification of Brussels also misses its beautiful and rich social tapestry, and discourages the well-off from moving there to enjoy its many delights and help revive the city. “Brussels is multicultural and will remain multicultural,” observes Ziani, lamenting that this “magical mixing of cultures” does not get through to the rest of the country.

Beyond Brussels’ villainous reputation lies a small metropolis of vibrant, energising diversity. Etched on to its native bilingualism, waves of immigrants have added to its rich patchwork.

But this tapestry is becoming patchier, as Belgium drifts towards polarisation, according to Badra Djait, an Algerian-Belgian academic and researcher into Islamic extremism and immigration. This is reflected in how, while mainstream Belgium had its gaze turned exclusively towards the atrocities in Paris, many Muslims were transfixed by the civilian carnage and death caused by French air strikes in Syria. “Images are important,” emphasises Djait. “Foreign fighters were originally drawn to Syria by the ugly pictures they saw of the Syrian president’s atrocities.”

Many youth workers fear that the government’s security-centric and heavy-handed handling of the situation, as well as institutionalised racism and ignorance, will only make matters worse.

And this relative cluelessness is manifested in the misguided, panicked setting of priorities. Despite the painful austerity measures, prime minister Charles Michel somehow managed to dig up an additional €400 million [Dh1.56bn] for tighter security and the “war against terrorism”, but did not whisper a word about unemployment, discrimination and urban decay.

But, ultimately, people who feel they are integrated and integral members of society are much more resilient towards radicalisation. This requires huge investment in deprived inner-city areas, improvements in education there, creating better prospects for minority and majority youth, who are becoming increasingly marginalised and radicalised, and combating exclusionary ideologies, whether they be Islamist or Islamophobic, through dialogue.

Khaled Diab is a Belgian- Egyptian journalist

On Twitter: @DiabolicalIdea