One country watching carefully to see whether the recent Russian-American agreement over southern Syria works, is Lebanon. The reason is that the Lebanese realise that the Syrian border with the occupied Golan Heights is merely a continuation of the Lebanese-Israeli border, so that conflict along one would very likely extend to the other.

There continues to be uncertainty as to whether Iran will seek to undermine the agreement. Some observers believe that Tehran is looking to build up its military capabilities around Israeli territory, in such a way as to be able to launch rocket and missile attacks in the event of a wider regional conflict between Iran and Israel. What Iran seeks, therefore, is a balance of terror.

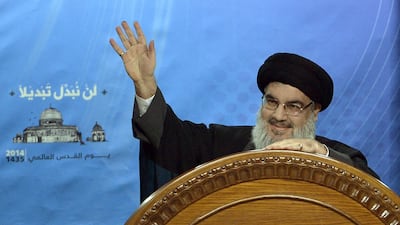

To those who hold such a view, Iran has no interest in respecting the Russian-American arrangement, which aims to prevent the deployment of pro-Iran forces along the borders with Jordan and the Golan Heights. When the secretary general of Hizbollah, Hassan Nasrallah, recently declared in a speech that a future war with Israel “could open the way for thousands, even hundreds of thousands, of fighters from all over the Arab and Islamic world to participate - from Iraq, Yemen, Iran, Afghanistan and Pakistan,” what he really meant to imply was that Israel would face retaliation from both Lebanon and Syria.

A more sanguine view is that Iran is not adamant about building up its military capacity near the Golan. Rather, its priority is to maintain control over the area between Damascus and Lebanon, to ensure the supply of weapons to Hizbollah in the event of a war with Israel. In other words it will not pay the political price of scuttling the Russian-American deal, but will seek to protect its most important stake, an open land road between Iran and Hizbollah in Lebanon, through Syria and Iraq.

For the Lebanese, either interpretation suggests that their own country, like Syria, is in the crosshairs of complex regional rivalries. The hope that Syria could become the primary venue for any Iranian-Israeli conflict, sparing Lebanon, now seems hopelessly naive.

If anything, the developments raise the risks for Lebanon. If Iran succeeds in opening a new Golan front, then it would regard this as an opportunity to expand the south Lebanese front, engulfing both Lebanon and Syria in any future standoff with Israel. And if it fails, there would be even more of an incentive to reinforce Hizbollah’s military power in Lebanon.

While Hizbollah’s military sway is considerable, does the party have any vulnerabilities inside Lebanon? While none are likely to dissuade it from engaging in a war with Israel, Hizbollah cannot ignore them.

For starters, it is behaving much as did the Palestine Liberation Organisation before 1975, when it transformed Lebanon into a front line for military operations against Israel. Ultimately, this alienated not only a significant portion of Lebanese, including, ironically, the Shia community of southern Lebanon who paid a heavy price for Palestinian actions, it also led to Israel’s military invasion and expulsion of the Palestinians in 1982.

There is no way Israel can force Hizbollah out of Lebanon, since the party is Lebanese. But what it can do, and intends to do, is make the price of a war so costly to the Lebanese in general, that they would do everything in their power to prevent Hizbollah from embarking on any new adventure. The problem with this rationale is that there is a high likelihood that it would at best delay a future conflict, without discouraging Hizbollah from continuing to play a vanguard role in Iran’s regional agenda.

To the Lebanese, this sense of inevitability is familiar. The country has long been a playing field for regional enmities, as its divided society is incapable of putting up barriers to armed groups wanting to exploit and overwhelm its system of sectarian consensus. That was true of the PLO and it is true of Hizbollah -- in the Palestinians’ case to their own detriment.

It is hard to imagine a unified opposition to Hizbollah emerging from within Lebanon. However, it was equally difficult to see opposition to Syrian hegemony in 2004-2005, until the assassination of former prime minister Rafik Hariri unified a majority of Lebanese and forced a Syrian withdrawal. Yet because Hizbollah is a Lebanese party, the outcome of such opposition will not be a pull-out, but heightened risks of civil war.

There isn’t an inevitability here, but Hizbollah knows that the best way to remain strong is to discredit Lebanon’s system of sectarian compromise, something it has done by blocking the system on numerous occasions. Once a sense of shared purpose in a consensual state disappears, the party believes, it will be in a better position to divide and conquer.

It’s with all this in mind that the Lebanese are looking towards Syria, hoping that the situation in the south remains contained.