New US President Joe Biden has hit the political ground running. Confronted by huge crises, most immediately the coronavirus pandemic and associated economic downturn, Mr Biden has wasted no time in initiating one of the most ambitious governance agendas in American history. But much of it may hang on the future of a poorly understood and arcane Senate rule known as the filibuster.

Democrats and Republicans are now split evenly in the 100-seat Senate, which must approve all legislation.

If there is a strict party-line vote of 50-50, Vice President Kamala Harris can cast a tiebreaking 51st vote. That solves Mr Biden's problems if all Democrats support his preferred legislation and a simple majority is required for passage, as is the case in the House of Representatives and almost all legislative bodies around the world.

That's how it was in the Senate, too, originally, but over time a system has evolved where, on most legislation, a super-majority of 60 is needed to "end debate" and allow a vote.

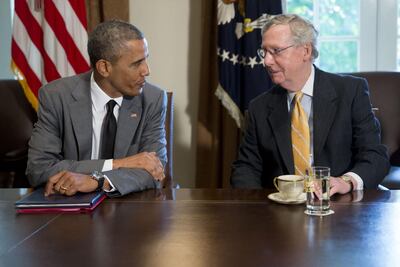

During the presidency of Barack Obama, the routine use of the filibuster by Republican Senate leader Mitch McConnell – who said his main priority was to try to ensure that Mr Obama was a one-term president – illustrated how the filibuster has become a crippling obstacle.

It's clear that elimination or reform of the filibuster is necessary for the US government to operate without relying almost entirely, as both Mr Obama and his successor Donald Trump did, on executive orders.

The US Senate is arguably the world’s most eccentric legislative body. And the filibuster is the most noxious of its byzantine maze of irrational rules. As Alexander Hamilton and other framers of the Constitution noted, the disastrous Articles of Confederation – the first American system – demonstrated that requiring super-majorities might seem to invite compromise, but in practice invariably promotes obstruction.

The Constitution avoided super-majorities except for impeachment and constitutional amendments because its framers had seen that minorities find it hard resist the temptation to embarrass majorities by blocking them at every stage if they easily can – exactly as in the contemporary Senate.

The change developed slowly.

The Senate abolished the power of a simple majority to force a vote on an issue, essentially by mistake, when it revised its rules in 1806. This loophole was later seized upon by defenders of slavery led by the notorious Sen John Calhoun. Later still, it became a favourite tool of segregationists, led by Sen Richard Russell. In 1917, Senate Rule 22 set the required number to allow a vote at two thirds. In 1975, it was reduced to three fifths, or 60 votes.

During the 20th century, filibusters were rare, primarily used by southern senators to block civil rights legislation and defend white supremacy. In the 21st century, however, the filibuster has become a constant feature of all Senate business.

Mr Obama faced such obstructionism on his appointments that his Senate allies eliminated super-majorities for confirming officials in 2010. Republicans extended that to include Supreme Court nominations in 2017.

Mr Biden just got his $1.9 trillion coronavirus relief package passed in both the House and the Senate, but only because of another bizarre rule: budget reconciliation. Created in 1974, it allows certain budgetary measures to be passed by simple majority – an obvious acknowledgment that the filibuster makes essential governance unworkable. "Reconciliation" is also how Mr Trump passed his only significant piece of legislation, a huge tax cut for corporations and the wealthy.

The Senate calls itself "the world's greatest deliberative body". That's risible. In fact, it is no longer a deliberative body at all. These days, reconciliation aside, it is not a governing body either. As veteran Senate staffer Adam Jentleson explains in his new book Kill Switch, the Senate now typically functions as an override mechanism shutting down legislative work altogether.

That suits Republicans, who have in recent times become a persistently minority party. They have also become a doggedly obstructionist party, whose only guiding principle appears to be unshakable loyalty to Mr Trump and alignment with his mercurial views. But even before the Trump personality cult, Republicans were clear on what they categorically opposed, but had virtually no practical agenda. For example, they zealously opposed Obamacare, but for more than a decade have never proposed any healthcare alternative.

Mr Biden wants to follow the now-adopted coronavirus bill with a major infrastructure initiative, climate change proposals and other urgent measures. Since few Republicans appear willing to support even the coronavirus package, it is hard to see how Democrats can forego reforming or eliminating the filibuster.

That won't be easy. Even a simple majority will be elusive because some conservative Democratic senators, especially Joe Manchin of West Virginia, will probably resist major changes. That’s partly to mollify Republican-leaning constituents. More importantly, the filibuster ensures their institutional clout. Without it, Mr Manchin and the others would be far less relevant. As things stand, they are central to most horse-trading.

Major filibuster reform, at a minimum, is essential to Mr Biden's prospects. Use of the filibuster could be restricted, the numbers required reduced, or other measures taken to limit its obstructionist power.

The filibuster originated in a mistake, mainly took shape in defence of slavery, was largely consolidated in defence of segregation, and now functions, as it always has, primarily as a tool of a recalcitrant minority blocking majority decisions. Indeed, it's now central to chronic American minority rule.

Republicans will claim Democrats are acting cynically and will regret such reform when Republicans once again have a majority. But it's irrelevant. Obstruction by Democrats wouldn't be particularly preferable to that by Republicans. Obstruction itself is the problem.

The obvious institutional and political imperative for reform is far more important than motivations. And it's likely that, without a powerful filibuster, the incentives and potential for cross-party compromises would actually greatly increase in the Senate.

Many Democratic traditionalists, including Mr Biden, are uneasy about reforming, let alone eliminating, the filibuster. But their agenda and fortunes depend on it. Moreover, elimination or at least reform of the filibuster would restore rationality and the original constitutional design to the Senate.

The excision of this malignant tumour from one of the central organs of the American body politic is one of the greatest legacies this Senate and the Biden administration can bequeath to future generations.

Hussein Ibish is a senior resident scholar at the Arab Gulf States Institute and a US affairs columnist for The National