But for the series Manhunt: Unabomber, currently playing on Netflix, few people under the age of 60 would have heard of Ted Kaczynski and the 17-year campaign of terror he waged against what he saw as the runaway Frankenstein's monster of technological progress.

There is some irony here. Kaczynski dismissed television as “an important psychological tool of the system”, designed to control the masses – but now the box-set generation has been introduced to his murderous mission to halt what he believed was the erosion of human freedom and dignity by our unthinking embrace of technology.

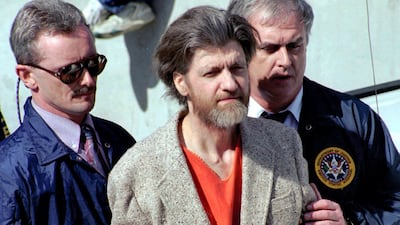

This year marks the 40th anniversary of the start of that campaign. Between 1978 and 1995 the Harvard-educated maths genius, who became known to the FBI as the Unabomber, planted 16 bombs, killing three people and injuring 23 more. Most of his targets were involved with technology, albeit to varying degrees. He was caught only when the New York Times and Washington Post agreed to publish his 35,000-word manifesto called Industrial Society and its Future and its themes were recognised by his brother, who turned him in.

Kaczynski, who had retreated to an off-grid cabin in Montana to plot the overthrow of technological society, was quite literally the proverbial voice in the wilderness. Forty years on, however, it could be argued that the Unabomber was a visionary to whom we should all now be paying very close attention indeed.

Of course, it goes against the grain to credit a killer. But as Dr David Skrbina, a philosophy lecturer at the University of Michigan-Dearborn, puts it: “The challenge is to make a firm separation between the Unabomber crimes and a rational, in-depth, no-holds-barred discussion of the threat posed by modern technology”. Kaczynski, says Dr Skrbina, “has much to offer to this discussion [and] his ideas have no less force, simply because they issue from a maximum security cell”.

If anything, technological developments in the world outside that cell in the past 40 years have served only to reinforce Kaczynski's message. Take the so-called "transhumanism" movement, with futurists such as Ray Kurzweil gleefully herding us towards the dystopian surrender of our humanity, to a hybrid amalgamation of artificial intelligence and flesh and blood – the so-called singularity, upon us as soon as 2029, according to Google's blue-sky thinker. This was a theme embraced by electric-cars-to-rockets multi-billionaire Elon Musk at the World Government Summit in Dubai last year. In the fast-approaching era of artificial intelligence, he proclaimed, human beings must merge with machines or become obsolete.

In his manifesto, Kaczynski wrote cogently of his fear that “the technophiles are taking us all on an utterly reckless ride” and that technology “will eventually acquire something approaching complete control over human behaviour”. He was especially fearful of the rise of artificial intelligence – a concern shared today by thinkers including the cosmologist Stephen Hawking. “A super-intelligent AI,” Professor Hawking has warned, “will be extremely good at accomplishing its goals and if those goals aren't aligned with ours, we're in trouble.”

Kaczynski was way ahead of him. Twenty years earlier, he predicted that computer scientists would “succeed in developing intelligent machines that can do all things better than human beings. As society and the problems that face it become more and more complex and as machines become more and more intelligent, people will let machines make more and more of their decisions for them”.

Eventually “the decisions necessary to keep the system running will be so complex that human beings will be incapable of making them intelligently”, at which stage “the machines will be in effective control”. People won’t be able to turn off the machines "because they will be so dependent on them that turning them off would amount to suicide”.

Think of the astonishing and largely unforeseen technological developments that have taken place and the ethical and social dilemmas many of them are now posing, in the 40 years since Kaczynski made his first bomb: the internet, the personal computer, supercomputer, tablet, smartphone, mass surveillance, GPS, email, wifi, broadband, nanotechnology, genetic engineering, robotics, wearables, drones, autonomous vehicles – to name a few.

Then there’s the rise of giants like Google, Facebook and Twitter, tracking and harvesting every facet of our digital lives, to say nothing of the Trojan horse toys we willingly bring into our homes, such as Amazon’s Echo and Google’s Home – always listening, increasingly watching and constantly learning about you and your habits.

Consider Kaczynski’s observation that “if the use of a new item of technology is initially optional, it does not necessarily remain optional because the new technology tends to change society in such a way that it becomes difficult or impossible for an individual to function without using that technology”. Now contrast that with the declaration by the United Nations that access to the internet is nothing less than an inalienable human right, right up there with food, shelter and education.

Which of this doesn’t chime with Kaczynski’s fear that the human race might “drift into a position of such dependence on the machines that it would have no practical choice but to accept all of the machines’ decisions”, at which point “the human race would be at the mercy of the machines”?

The scale of the intrusion of technology into our lives is now so extensive and complex that it is near impossible for individuals to grasp. But some technologists, at least, are starting to wonder if it isn't all getting out of hand – and in the process are beginning to sound an awful lot like Kaczynski.

Last week the San Francisco-based Centre for Humane Technology, a group of “deeply concerned former tech insiders”, launched a campaign to “realign technology with humanity's best interests”. Technology, it announced, “is hijacking our minds and … eroding the pillars of our society: mental health, democracy, social relationships and our children”.

As a 75-year-old man serving eight consecutive life sentences in a maximum security prison in Colorado might be forgiven for saying, I told you so.