History’s biggest plot twists rarely arrive with drum rolls. They creep up quietly, without fanfare, until suddenly they are obvious and irreversible. We are approaching one now.

The planet is undergoing three population mega-trends at the same time, and together they will reshape economics, geopolitics, migration and even the meaning of work.

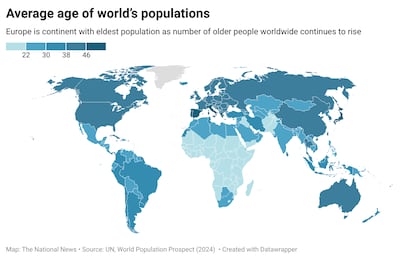

On one side, advanced economies are ageing rapidly. On the other, much of the Global South is experiencing the largest youth boom in human history. One world is running out of workers. The other is overflowing with young people searching for opportunity. Between them sits a third force: machines powered by AI that do not age, do not sleep and are becoming smarter by the month.

This is not simply demography. It is a restructuring of the global system, and governments must make strategic decisions now.

In countries such as Japan, Italy and Germany, the median age is well above 45. That statistic becomes stark when translated into fiscal reality: fewer working-age adults supporting more retirees for longer periods. As this trend accelerates, welfare systems will be strained.

Pension models designed for large families and shorter lifespans now operate in reverse – small families, long lives, rising healthcare costs and shrinking labour forces. The result is structural pressure on public finances and growing political tension between generations.

The politics of ageing is already visible: debates over retirement age, tax burdens, healthcare spending and immigration. Older societies tend to become more cautious. Risk appetite declines. The median voter shifts towards protecting what exists rather than investing in what could be. That may provide short-term stability but can slow reform precisely when reform is most urgent. Brexit is one example of this broader dynamic.

The uncomfortable truth is that the welfare state was built for a different demographic planet.

Now zoom out. Across Africa and parts of Asia, the Middle East and Latin America, populations are younger, faster-growing and intensely connected. Africa’s median age is about 19, compared to the low-to-mid 40s in much of Europe. By 2030, roughly two-fifths of the world’s youth will be African.

This could be a historic growth dividend. A young population can drive energy, invention and entrepreneurship – if it is educated, employed and productive. Youth gives economies momentum.

However, youth can also become an opportunity trap. Many emerging markets already face youth unemployment above 20 per cent, and in some cases above 30 per cent. A large generation entering economies that cannot absorb them is not a dividend; it is a pressure cooker.

Compounding this is a generation that grew up online. They are globally aware and locally impatient. They compare their lives not to their parents’ past but to someone else’s present, instantly, in real time. They expect speed, transparency, dignity and mobility. When systems fail, frustration spreads quickly.

The demographic divide therefore creates two anxieties: rich countries fear they will not have enough workers; young countries fear they will not have enough jobs.

Migration appears to be the logical bridge – moving labour from surplus to scarcity. In theory, it could become the great balancing mechanism of the 21st century. In practice, it has become one of the most polarising issues in politics.

Just as the world wrestles with this human imbalance, it collides with a machine revolution. Robots and AI will more than just replace jobs; they will reorder the job ladder. Many predictable, repetitive roles are most exposed. Roles requiring complex judgment, creativity and leadership will expand. The dividing line is no longer blue-collar versus white-collar, but automatable versus non-automatable.

For ageing economies, automation is a lifeline. If the workforce cannot grow, productivity must. Japan’s robotics leadership is not a fad or simply advancing the tech-industry, it is a demographic strategy. For young economies, automation presents a paradox. It can help leapfrog inefficiencies and build new sectors, but it can also shrink the entry-level jobs that historically absorbed millions of young workers.

Countries such as the UAE sit at the intersection of these trends: connected to ageing, capital-rich economies, close to youth-rich regions, experienced in talent mobility and investing heavily in AI and advanced industry.

The opportunity is far larger than importing skilled workers. The real leap is to become a global platform that converts demographic turbulence into economic advantage. That means building skills pipelines, not just issuing visas – starting in schools, technical institutes and cross-border credential systems. It means treating AI as a productivity strategy, not a gadget – raising output, creating high-wage jobs and building new export sectors. And it means investing in youth economies across Africa, South Asia and the Middle East, because shared prosperity is the smartest stability strategy: creating opportunity where people live reduces forced migration while expanding markets.

The demographic divide is not “their problem” or “our problem”. It is one global system under stress. The answer will not lie in political slogans but in smarter “talent corridors”. These will be migration systems that are legal, circular, skills-based and mutually beneficial. Migration should not be treated as a one-way exit but as a development circuit: training partnerships, recognised credentials and portability of benefits.

The old model saw migration as a leak. The new model can treat it as a loop.