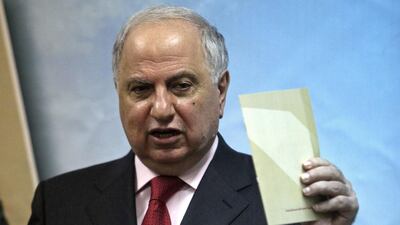

The recent death of Iraqi politician Ahmed Chalabi brought forth a wave of highly critical obituaries in western media. The gist was that Chalabi had hoodwinked the Bush administration by peddling false intelligence about Saddam Hussein’s weapons of mass destruction. The implication was that the United States had been fooled by this shifty Arab.

Chalabi was no choirboy, and his pursuit of a policy of de-Baathification, effectively a policy of de-Sunnification, in Iraq after 2003 did much to exacerbate sectarian relations in the country.

However, the argument that Chalabi somehow engineered America’s intervention in Iraq was ludicrous. If anything, the Bush administration invited the Iraqi politician to push it into action it had already intended to pursue.

Four months after the September 11, 2001, attacks, President George W Bush made his “axis of evil” speech, identifying Iraq as one of three countries helping terrorists, possessing weapons of mass destruction and building nuclear weapons. This was the intellectual rationale for the war against Iraq, long before Chalabi allegedly brought fabricated information to the table.

It was no surprise that when Chalabi saw the mood in Washington shifting against the Iraqi regime, he sought to keep the momentum going. After all Mr Bush’s predecessors, George H W Bush and Bill Clinton, had also approved of regime-change in Iraq, but failed to put any teeth into that policy.

At last seeing an opportunity to make headway after a decade in the largely marginalised Iraqi opposition as leader of the Iraqi National Congress, Chalabi seized the opportunity. He may have been a manipulator, but given long-standing American divisions over Iraq, Chalabi’s actions were understandable.

The problem is that the United States provokes conduct such as his through the way it portrays itself to the world. Because the country identifies as the hope of democrats everywhere and the upholder of human rights and humanitarian values globally, it is inevitable that those like Chalabi will play on this.

The situation in Syria is a good example. For almost five years the Obama administration has limited its involvement there, despite horrific abuses of human rights and the US’s stated commitment to prevent the use of chemical weapons in the conflict.

While many in the United States have welcomed the policy not to get too involved in Syria, in the Middle East the reaction has been very different. A region that has long denounced American action as a form of neo-imperialism is today aghast that it got what it asked for. By wanting to leave the Arab world to its own devices, the administration has, ironically, elicited moral condemnation.

In other words, America’s image as a defender of morally-just causes – and everyone considers his or her cause morally just – ensures that those seeking American support will do everything to impel American officials to advance their agenda. Chalabi’s fault, it seems, is that he succeeded after 2001.

That is not to deny that he was a man often difficult to trust. Chalabi was too smart to be mistaken for an idealistic naif, nor did he pretend to be one. Yet many in the West often prefer someone who comes across as an earnest moral paragon rather than a man in a silk suit exuding wiliness. This tells us much more about western perceptions of politics than anything else.

Perhaps Chalabi might have considered the fate of another personality to determine his own actions. Nelson Mandela embodied the morally upright and principled dissident. Look how much good that did him. He was imprisoned for decades by the South African authorities who were backed by the United States during the Cold War, whatever the American views of apartheid.

Chalabi did not aspire to be a sainted loser, popular with the liberal media but consigned to permanent triviality. That’s why if criticism is to be directed at the man it must be in the context of his post-2003 political career, not his pre-war behaviour.

He can be taken to task for having done little to end sectarian animosities in Iraq after the war; quite the contrary. This was one case where the consummate dealmaker, in his pursuit of political power, saw an interest in allying with Iran and the Shia political parties, whatever the price in terms of Iraqi stability.

As Gareth Smyth wrote in a perceptive obituary for The Guardian: "He saw no contradiction between being a proud Iraqi nationalist – who spoke even English with a heavily accented 'qaf' – and a Shia with close links to Iran and Lebanon."

All this showed that in the end Chalabi was a product of his environment, not America’s tool. Having attained his goal, he returned to playing the complex, contradictory politics of Iraq and the Middle East towards which so many westerners feel hostile. Alliances change and loyalty is only to one’s own.

In death Chalabi is still paying for this western uneasiness.

Michael Young is opinion editor of The Daily Star in Beirut

On Twitter: @BeirutCalling