The Middle East has endured profoundly disruptive and traumatic geopolitical forces over the last century, from the collapse of the Ottoman Empire to the ascent and decline of western empires. The destruction wrought by the unjustified and disastrously-managed United States occupation of Iraq has also inflicted tragic suffering on the region.

The US has been blamed – and blames itself – both for intervening and not intervening in the region.

As it seeks to shift greater security responsibilities to the states of the region, what must change in practical terms?

On Syria, the first priority ought to be elimination of the most extreme Islamist groups. That should not mean partnering with Bashar Al Assad or his allies, as it is unjustifiable to fight one evil with an equally diabolical one.

It is also questionable whether ostensibly moderate rebels operating in coalition with the Islamist extremists should be supported, considering that they are effectively furthering the extremists’ cause.

A better option would be for a condition of continued military aid to require the moderates to disengage and reform as a viable fighting force independent of the extremists. Let the Syrian military and the extremists wear each other down in the meantime.

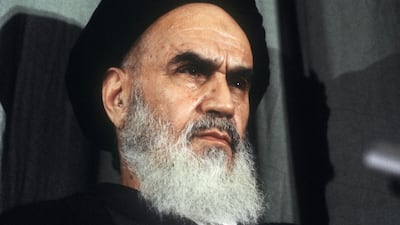

Parallel to this, the US will probably have to engage with Iran on the Israeli-Palestinian issue as this is the primary reason why Iran is so vested in Mr Al Assad’s survival.

It is also one of the reasons why Syria probably would not remain stable for long even if Mr Al Assad did manage to take back most of the country: eventually but inevitably, Iran would resume its proxy campaign against Israel.

Therefore, unless the US wishes to gamble on forcible regime change in Tehran, which it does not, engagement on the Israeli-Palestinian issue is inevitable – however vociferously the Israeli lobby in the US will protest against it.

Progress on this issue is doubtful, however. The US will first have to reinvigorate its own resolve on the two-state solution before seeking to convince others.

On Iraq, although progress continues against ISIL, the political situation in Baghdad will remain up to Iraqis to solve, perhaps led by Muqtada Al Sadr if the Iraqi parliament remains unwilling to hold itself accountable to the Iraqi public.

A degree of rapprochement between the US and Iran – again, dependent in part on deeper dialogue on issues of mutual importance – could improve the chances of Iraqi reunification.

On Yemen, western observers vary on the degree of Houthi ideological alignment with Iran, versus payment of lip service to Iranian rhetoric as a means of attracting military aid.

The GCC should continue to communicate its willingness to talk with the Houthis on condition that they cease propagating their toxic rhetoric and terminate their alliance with former president Ali Abdullah Saleh, who proved to be hopelessly corrupt and a serious obstacle to the counterterrorism campaign against Al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula.

As the US cautiously but deliberately steps back from a region it is attempting to guide towards positive-sum solutions, it is up to the leaders and people of the region to pursue a vision of peace and prosperity over dominance and devastation.

Thomas Buonomo is a geopolitical risk analyst with Stratas Advisors