Eye implants made in Dubai are being developed as a potential solution for the more than 12 million people around the world awaiting corneal transplants, said Dr Valentyn Volkov, founder of tech company Xpanceo.

He described the technology as “the beginning of a new era” in vision restoration, offering hope to patients facing long waits for donor tissue.

Xpanceo, based in Dubai Knowledge Village and specialising in next-generation smart contact lenses, has linked up with Italian start-up Intra-Ker to develop an intracorneal implant capable of restoring sight in patients with corneal blindness.

The condition typically arises from scarring caused by infection, trauma, or incorrect contact lens use, leaving millions with limited vision.

Due to a global shortage of donor tissue and a high failure rate, only about 185,000 corneas are successfully transplanted each year, leaving the vast majority of patients facing long-term sight issues, particularly in developing countries. A cornea can be donated up to 24 hours after death, the UK’s National Health Service says.

The implant uses a projection system similar to that in a smart contact lens, delivering visual information directly to the retina and bypassing the need for a transparent cornea. Dr Volkov said the technology offers a new way to restore vision for patients who might otherwise face years of partial blindness.

“Until now, implanting electronics in the anterior segment of the eye has not met with success,” said Prof Massimo Busin, who is chief executive of Intra-Ker. “With only 185,000 traditional corneal transplants performed each year, we see a critical need for solutions that don’t rely on donor tissue.

“This system is made possible by our IP protected technology, which enables precise and safe implantation of sealed electronic components, using a procedure no more complex than standard corneal surgery.”

Global research

Research to create a bioengineered cornea has been under way for more than a decade, particularly in Australia.

But rather than replace a damaged cornea with a bioengineered alternative, the implant developed in the UAE and Italy addresses the challenge of information delivery to the brain.

The cornea’s usual optical function is replaced with a tiny computer interface – a technique which moves away from the typical solution of replacing biological tissue, towards visual rehabilitation driven by precision-engineered technology.

Human vision requires light passing through a transparent cornea and on to the retina, where it is converted into neural signals sent to the brain.

When the cornea is damaged, the visual pathway is blocked, even if the retina is fully functional.

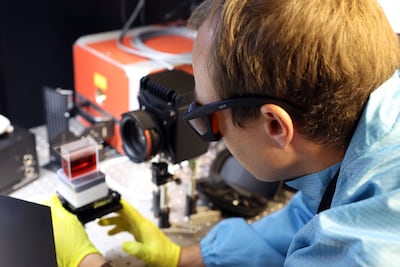

In a trial using an eye from a human donor, the implant successfully projected clearly distinguishable images on to the retina. In further tests, a tiny device captured visual data using external smart glasses equipped with an embedded camera.

Data was then wirelessly transmitted, using the same microtechnology developed for Xpanceo’s smart contact lens prototypes, on to a tiny display implanted inside the damaged cornea. Content was then projected directly on to the retina, restoring vision without the need for any donor tissue.

Dr Volkov said researchers were now working on reducing the size of the system to make it medical grade.

“The initial proof of concept combined a 450x450 pixel display with our micro-optical projection system into a 5.6mm package, so for clinical use we aim to miniaturise the entire system,” said Dr Volkov. “With more than 12 million people awaiting corneal transplants, we see this as the beginning of a new era, where advanced optics and computation can bridge long-standing gaps in vision care.”

Over the next two years, Xpanceo aims to develop a surgically implantable version for clinical trial, using biocompatible materials inserted in a similar procedure similar to standard corneal surgery.

Cost barriers

Cost could yet prove a significant barrier to rolling out the technology on a wide scale, although a potential price for the replacement lens has not yet been revealed.

“A successful corneal transplant can restore vision for many years, but longevity depends on the type of graft, underlying condition, and immune response,” said Dr Hossameldeen Elbarbary, a consultant ophthalmologist at NMC Specialty Hospital, Al Nahda, Dubai.

“However, about 20 to 30 per cent of grafts fail within 10 years, requiring repeat surgery.”

The waiting time for done tissue varies by country and the availability of eye banks.

In high-income countries with established donor supplies, waiting time can range from weeks to months, but in other regions patients can be waiting years.

An alternative technology that delivers images directly to the retina, bypassing the cornea, would have a profound patient impact, Dr Elbarbary said.

“The global shortage is one of the biggest challenges in corneal blindness management,” said Dr Elbarbary. “This technology would eliminate the need for donor tissue, addressing that global shortage of corneas while also reducing surgical risks such as infection and rejection.

“That said, such devices are still in the early stages. Safety, biocompatibility, visual quality, and affordability will need rigorous testing before widespread use. But the potential is truly groundbreaking.”