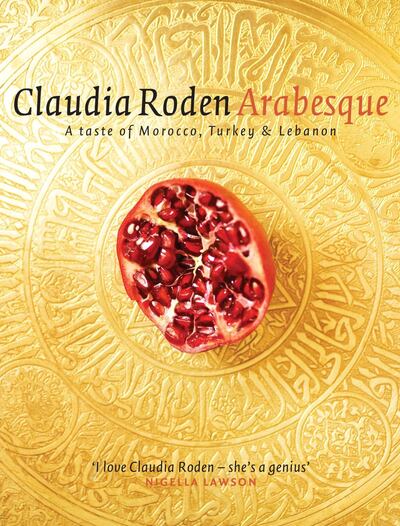

Between 1968 and the present day, Claudia Roden has published A Book of Middle Eastern Food, Tamarind and Saffron, The Arab-Israeli Book and Arabesque: Sumptuous Food from Morocco, Turkey and Lebanon, to name but four of her 20 books on food.

Her influential works have seen her honoured with a fellowship at SOAS University of London and an Observer Food Monthly Award in 2019. It is little wonder that the writer and cultural anthropologist is considered an eminent champion of Middle Eastern cooking in her home city of London.

Roden, 84, has just sent off the manuscript of her latest cookbook, with the working title The Med, to Penguin, which she anticipates will be published next autumn.

She spoke to The National as the UK entered a second winter lockdown, leading many to turn to the comfort of cooking at home with family and friends, as restaurants shut doors until the end of the year. The pandemic, Roden says, has prompted a "big change" and "people are cooking more".

Accordingly, The Med is aimed at a millennial demographic, reflecting the "tremendous appeal in wanting to cook" that Roden sees among young people.

The original food influencer

"Claudia's research on Middle Eastern food is really second to none. These are the guidebooks we all go to, to find out reliable, formative information. That is unique," Yotam Ottolenghi, chef, restaurateur and author of bestselling titles Simple (2018) and Flavour (2020), told The Guardian in 2019.

Indeed, Roden is one of the most important voices on contemporary Middle Eastern cooking trends in the West. Her first publication, A Book of Middle Eastern Food, broke new ground in the 1960s, introducing the complex historical legacies of Ottoman, Arab, Jewish, Persian and North African cuisine to a British public used to the exotic delights of "mushroom omelette and spaghetti Bolognese".

“Everybody is using tahini and sumac now,” she exclaims, when asked about the current popularity of Middle Eastern food in the UK. Roden says that a line of influence can be traced back to her early writing. “On one occasion, Ottolenghi told me that when he came to the UK to study French patisserie, people were asking him for recipes from his own culture. .. [and he] said he copied lots of recipes out of my book by hand and gave them to people!”

Roden says that this influence has now come full circle. "So many younger chefs have been influenced by A Book of Middle Eastern Food and now I'm influenced by them — because I go to their restaurants and I see what they're doing."

A thirst for cultural and cuisine

It hadn’t always been this way. When Roden came to the UK from her native Egypt, a few years before the Suez Crisis of 1956, perceptions of Middle Eastern and North African cuisines were very different. A parochial British understanding of “the colonies” and their food had led many to speculate about lambs' heads and organs.

“The British were colonisers. When they were in the Middle East, they never wanted to eat the local food. When I was at the English School in Cairo, we ate just English food – and not terribly well-cooked English food,” she says.

Roden was born into a mercantile Egyptian-Jewish community in 1936, which had migrated from Ottoman centres of trade on the overland silk and spice routes, such as Aleppo and Istanbul. Her family found themselves in the bustling city of Cairo that had access to the key shipping route of the Suez Canal. After Abdel Nasser nationalised the canal, many Jewish Egyptians came to the UK as refugees, including Roden’s extended family.

The recipes for her first book were sourced from a community of refugees who found themselves in London during the 1950s and 1960s. “There had been 80,000 Jews in Egypt – and they were exchanging recipes as a form of remembrance saying: ‘I might never see you again. Give me that cake recipe, and that’ll be my way of remembering you.’”

These refugees brought a particularly cosmopolitan vision of Mena with them. “This is why I did a book on Middle Eastern food, not Syrian food or Egyptian food – because the Jewish community was very mixed. They were from Thessaloniki, Izmir, North Africa and from all over the Mediterranean,” says Roden.

She sees the same spread of food through migration today. “A lot of refugees from the current Syrian civil war find themselves as chefs because it’s the one thing they can go into without any capital: they can cook.”

Roden was also keen to rediscover the Islamic culture of Egypt and the Middle East. “I was very interested in the Arab culture that I, in a way, never had. We spoke French at home. But my father’s family spoke Arabic among themselves … I felt that loss of a culture.”

Cook to have a good time

Consequently, she has become a gastronomic archaeologist, tracing the Islamic culture she was “never taught at school”, through empires and trade. “A dish that is now in Catalonia, I also found in Konya, which was the capital of the Seljuk Turks. It’s a bit like archaeology, finding clues to what had happened before.”

Although Roden says that even a smell can conjure up a civilisation, she is not just focused on the past. “I wouldn’t want these traditions to ever disappear, but at the same time chefs and people cooking at home have no obligation to cook exactly as others do in a different country.”

Despite her deep historical knowledge, Roden's food writing, including in the upcoming The Med, is based on an altogether more intimate engagement with cooking, entertaining and socialising, both around the dinner table and across borders, something she has missed during the current lockdown. "I just wanted to invite people to dinner and have a good time. I wanted to find a dish that gives the greatest possible pleasure. But also I didn't want to work too hard because I wanted to be with my guests."