Foraging for mushrooms in the brush near Umm Qais, fishing for tuna in Aqaba, visiting grape farms with volcanic soil in the fertile Mountain Heights Plateau, enjoying a fine-dining menu of locally sourced ingredients in Fakhreldin, one of Amman's most famous restaurants. These are only a few activities that will make up Farm to Fork Jordan's culinary-focused travel itineraries.

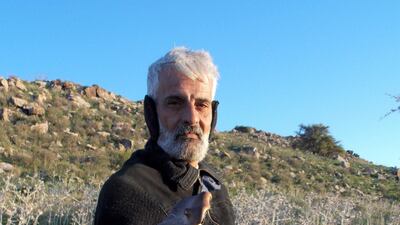

Concept founder Nico Dingemans hopes to draw conscientious travellers and food lovers from around the world to the country through the new tourism strategy, which will take in the guided tours mentioned above.

“You can learn so much about a country through food,” Dingemans says. “When you visit Italy or China this is normal, but not in Jordan.”

Dingemans says the country primarily banks on people visiting Petra, the Dead Sea or Wadi Rum. Each is absolutely worth seeing, he says, but visitors don't get the chance to learn about Jordan's culinary heritage, which is where the Farm to Fork project comes in.

Farm to Fork: a history

Dingemans, whose new book Farm to Fork Jordan is due to be published in August, kick-started the concept in his native Netherlands. He is half-Indonesian, half-Dutch, and grew up all over the world, eventually starting a career in hospitality working for Hyatt, then Hilton. His job took him back to Indonesia, to Belgium and the US; he wrote about traditional Chinese medicine in Hong Kong, microbiotics in spa cuisine in Thailand, the benefits of the Mediterranean diet in Italy and agriculture in the Netherlands. This led to the publication of From Farm to Fork in the Netherlands, a book featuring 24 chefs from the country's 12 provinces.

"It was the culinary identity of the region at that moment," he says. The book discussed soil, ingredients, the food chain and, most importantly, highlighted Dutch farmers and chefs. "It's very difficult to get Dutch chefs to be proud of their culinary heritage. They're not like the Italians or French or Spanish," Dingemans says. A pride in their culinary culture aside, the project spurred chefs to work more closely with local farmers.

Dingemans took on a similar project in Curacao, then headed to Amman in August 2019 on a short consultancy project to help Jordan River Wines restructure its tasting room. When the coronavirus pandemic hit, he was stuck and, without much else to do, he began to delve into Jordan's food history, where he found similarities with the Netherlands.

“There is no lack of food stories and history or tourism businesses, but they lack this sort of pride. There’s a tendency to fall faster in love with foreign food concepts,” he says. “But I’m a foreigner, so I see it differently.”

Variety is the spice of life

Dingemans says Jordan’s diversity is admirable. “You have people from Syria, Palestine, Egypt, you have all these influences from the Umayyad to Roman Empires, Chechen, Druze, people from Saudi. But Jordan has this mother goose kind of position. She also has her own eggs, the Bedouin and those from mountains where it’s more green … and all are welcome.”

Jordan is part of the Fertile Crescent. Its low elevation and dense oxygen makes for exceptionally fertile soil. The country's agricultural history goes back to the Nabateans, famed for their ancient irrigation system. It is also one of the few places on the planet identified by historians where humans began to domesticate plants and animals. It is home to some of the world's first known forms of bread-making and has hectares of olive trees.

“You can’t explain Jordan in two minutes. But once you’re in the story and it grabs you, it has so much to offer,” Dingemans says.

Hooked by the book

In Farm to Fork Jordan, Dingemans's goal is to highlight ingredients and the country's culinary history through storytelling. The book features 24 food items, 24 farmers, 24 chefs and 48 dishes across Jordan's 12 governorates.

It introduces readers to myriad culinary concepts: from products such as khobesi, a leafy green, and jameed (dried yoghurt), to how the country is growing tomatoes in hydroponic greenhouses. The chefs, meanwhile, range from Bedouins in Wadi Rum to Um Suleiman, the woman running Beit Al Baraka, a boutique hotel and restaurant in Umm Qais, to the team behind Fakhreldin. The hope is that visitors will read the book, and visit the restaurants or embark on a culinary tour.

Culinary tours

Farm to Fork's guided tours will take visitors across the country, from the mountains to the sea, and include trips to date and olive farms, walks to forage for herbs and mushrooms, diving for tuna and meals at the restaurants featured in the book, all while learning about the histories of the ingredients and current innovations.

"We're looking at Jordan through the lens of food," Dingemans says. Again, this is not a novel idea, but one he feels hasn't been tested in the Middle East in the same way it has elsewhere. He cites the example of truffle-hunting in Italy, which he says has become something of a phenomenon. "You have tourism, TV shows, articles … truffles are on the menu at every restaurant, there are tours. People know if they go during a certain period, they can buy truffles, do a cooking class with a nonna ... There's a whole campaign around it."

Dingemans thinks olive oil and dates can be Jordan's truffles. Its expanse of olive trees aside, Jordan has about 500,000 medjool date palms and plans to expand to a million over the next decade. A superfood, dates have become even more of a necessity during the pandemic and are also becoming more popular abroad.

Dingemans has begun conducting tours at Al Maida olive oil farm, and Farm to Fork's book and tours will also weave a narrative around dates, drawing in their history as a Bedouin staple, their health benefits, why they're eaten for the slow release of nutrients and sugar during Ramadan, and how modern restaurants are elevating them.

“Tourists get to meet people off the beaten track, those they wouldn’t normally seek out,” he says.

The future is local

The end game is to get visitors excited about Jordanian cuisine and to get chefs interested in cooking with local ingredients. “If you’re going to boost a country’s culinary tourism, the goal is to have more local sustainable agricultural products end up on the plate of Jordanian hotels and restaurants, to help farmers more,” he says. “Hotel owners should promote that and increase the percentage of products they buy from these farms. If everyone does that, we’re talking big numbers.”

Dingemans says this attracts guests, too. “Then you can say: ‘Oh, Marriott has a sustainability programme’ – and it will draw visitors.”

This, he feels, is mandatory. Worldwide, a younger generation of travellers is interested in socially responsible, sustainable travel. The European Commission released a Farm to Fork strategy as part of its European Green Deal, which requires 20 per cent of farmers within the region to be certified organic by 2030. That's millions of farmers whose food ends up in supermarkets.

Dingemans says the teenagers of today will become adults in a world where sustainable food is a minimum expectation. “They’ll take that expectation to any tourism destination they visit, so if you’re not prepared, you’ve got a problem,” he says.

Tourism makes up about 16 per cent of Jordan's GDP, so it's important that the country keeps up with trends, and attracts a new generation of discerning, conscious, adventurous travellers, those who are more willing to delve into a place and spend money within local communities.

“People like to do something good with their tourism dollars,” he says. “This gives them a way to do that while showcasing Jordan’s culinary strength.”

Farm to Fork Jordan will be available on Amazon, in bookshops and museums, and at the hotels and restaurants featured in it. It will also be available in the Gulf states, and Dingemans hopes it will inspire people to visit Jordan and take a soon-to-be-launched Farm to Fork tour once it's safe to travel again.