The term haute joaillerie is firmly entrenched in the lexicon of luxury fashion, and can be defined as a one-off creation that's handcrafted by the world's most skilled artisans over several months, and sells for hundreds of thousands of dirhams.

So I was understandably nervous about trying my hand at some of the jewellery-making techniques, at a workshop conducted by L'Ecole, School of Jewellery Arts. The Paris-based institution, which is supported by French maison Van Cleef & Arpels, has set up a travelling workshop and exhibition arena at Hai D3 in Dubai until Saturday, November 25. The session I attended, Trying Out the Jeweller's Techniques, is part of Savoire Faire (literally, "know how to do"), one of a series of three workshops that also include the Art History of Jewellery and Universe of Gemstones.

The session starts with an introduction by L'Ecole's deputy director Frédéric Gilbert Zinck, who takes us through the rich history of French jewellery as well as the finely tuned stages in the creation process. Every piece starts with a sketch, a design that, in high-jewellery collections, needs to be mindful of two seemingly contradictory concepts: it has to be unique as well as reference the maison's archives. "Heritage is extremely important in high jewellery," says Zinck. "At the same time, we often look to artists and designers who have not worked or trained in jewellery-related fields, so they can bring a free style to the themes they're assigned. They come up with hundreds of sketches, of which one may eventually be selected to be produced."

After a sketch has been finalised, the artists create the gouache: a coloured rendering of the piece, which has to accurately capture what it will look like when finished – from the exact depth and dimensions to the shades and facets of the stones, and the way light will reflect off them. Once the gouache has been approved by the maison, and the customer (if the jewel has been pre-ordered), it is sent to the stone-setters, who then seek the required gemstones. “Metal does not really exist in high jewellery, it’s only there to hold the gemstones. But finding the stones to match the gouache can be a long-drawn process, to get the exact shades, shapes and sizes. If a dealer or customer does not have the exact types and numbers of stones required according to the approved gouache, it may be put aside for months or even years until we can acquire them,” says Zinck.

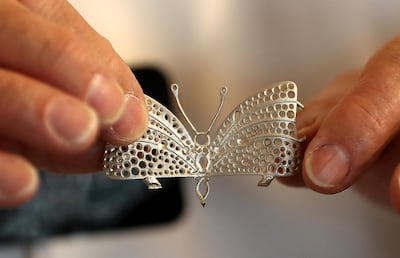

The next step calls upon the skills of master jewellers, who need to model the framework of the piece, which can be done in wax or by directly hand-carving the design on a plate of the base metal, usually gold. For example, the Van Cleef & Arpels ballerina brooches are first hand-sculpted in wax, while the flatter butterflies from the brand’s Alhambra collection are usually crafted straight off the metal.

The final step in the process is the polishing. In regular jewellery collections, pieces are typically polished once finished; however, high jewellery is polished between three and eight times, before and after a piece is set, and after it has been assembled. “Also, we polish the most remote parts, even if it won’t be visible to the eye,” says Zinck.

“There is no room for error here. If something goes wrong, even to the slightest fraction of a measurement, it is immediately discarded no matter what step of the process it’s at, and the jeweller, stone-setter or polisher must start over,” he adds.

Armed with this rather impressive information, we move on to the savoire-faire part of the workshop. Restricted to 12 people divided into two groups, the session is conducted by a master jeweller and a stone-setter, who demonstrate a total of four techniques and then guide their halves of the class to tentatively follow suit.

The curved work stations are set up to resemble a jeweller’s bench, complete with a lambskin bag underneath to catch and recycle the (usually gold) dust created when the metal is being filed. It seems easy enough when the instructor demonstrates how to hold the jeweller’s saw at a 45-degree angle in order to cut along a straight line, and at 90 degrees to make a curve, turning it in a semi-circular direction meant to resemble a flower petal. The mangled mess that ensues – what with our unsteady hands and unfamiliarity with the razor-sharp saw – makes me glad that we’ve been given silver plates to work with.

The wax will be easier to carve, we console ourselves. We are wrong; it’s a gruelling task. In theory, we work with a straight file to create a groove along what’s supposed to be a ballerina’s skirt, and a curved file to give it a raised, swishy effect. In reality, not only is it challenging for my two left hands to form the groove but, ironically, I also tend to put more pressure on the right side. As a result of this, even the hair-thin section I finally manage to carve – one ruffle on one skirt of one ballerina brooch – looks glaringly lopsided.

The group moves on to the stone-setter’s bench, where we learn about the various placements that gems can be set according to. For instance, the stones on the Van Cleef & Arpels’ ballerinas are placed using the bead setting (face), prong setting (wings) and hammer setting (body). Various types of graver tools are used to adjust the gems based on their shapes, and so that no metal is visible along the perfectly straight or distinctly curved lines of stones.

We try our hand at forming tiny suture-like holes where the stones would sit, labouring to create a straight line with barely any space between each puncture – by far the most successful task of the day, until we view our work under the loupe that magnifies the irregular gaps that got away from us.

The workshop ends with a polishing session, for which we use strips of soft cotton coated with two kinds of paste: a pink abrasive and a more fine-grained yellow one. The idea is to uniformly polish every line, curve and corner with varying degrees of pressure depending on whether the piece is flat or raised. "Polishing is what gives the piece its brilliance. But you have to be careful not to damage the metal; it should not bend or dip in places, otherwise the whole framework will have to be started from scratch," Zinck explains.

This degree of care and caution might explain why polishing a mere three-inch unadorned butterfly takes up to 40 hours, while stone-setters are able to mount between two and seven gems per hour. So, a piece with 1,000 irregularly shaped stones would spend about 400 hours at the stone-setter's station, fresh off its 700-hour journey with the master jeweller, not to count the time it takes for sketches and gouaches to be drawn, painted and approved, and gems to be sourced.

We may not have worked with precious stones in the L’Ecole workshop, and understandably so, but the process itself – or the bits of it we experienced and tried to emulate – was enough to leave a lasting impression and new respect for the exclusive world of high jewellery.

______________

Read more:

Le Secret, the tantalizing new jewellery collection from Van Cleef & Arpels - in pictures

Against the grain: Chanel’s latest high-jewellery collection takes inspiration from wheat

Exclusive: Bulgari’s creative director for jewellery tells us about her love for gems

______________