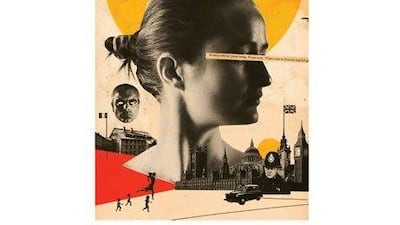

As divorce rates continue to soar across the world, Anna Blundy examines how far Western influence and social change in the Gulf countries have altered the mindset towards matrimony, and whether love really is the tender trap for many women.

A question asked by the relationship counsellor Mira Kirshenbaum in her book Too Good To Leave, Too Bad To Stay is: "If God, or some omniscient being said it was OK to leave your marriage, would you feel tremendously relieved and have a strong sense that finally you could end the relationship?" It is one that finds resonance with many women considering the terrifying step of divorce. So many of us would go if only we had divine permission.

There is so much pressure to make marriage work, from family, friends and society at large. Think of all those people who came to the wedding and brought presents. Would you be letting them down? What about the parents, brothers and sisters who were so happy to see you start a family and settle down? And that's not to mention the most important people concerned - the children.

The media compound our fears. In the 1979 film Wa la azaa lel sayyidat (Ladies Should Not Offer Condolences), the problems faced by divorced Arab women were brutally outlined. The film tells the story of Rawya, a woman who succeeds in divorcing her husband after he fails to provide for her and their daughter. When she finds love again, Rawya's ex-husband reappears on the scene, spreading vicious rumours about her, rumours that lead her new lover to desert her.

And let's not forget the 1975 Egyptian classic Orid Hallan (I Need a Solution), starring Faten Hamama, who plays Fawzya, a woman seeking to dissolve her marriage to an adulterous diplomat. When her husband refuses to divorce her, she goes to court, but, by using legal loopholes, he makes it impossible for her to end the marriage.

Terrifying warnings indeed, but do these old films still have any relevance to woman today?

Sofiya Jacobs, 38, has four young children, all boys, all under 11. A Saudi married to an Italian, she remained in a sporadically abusive relationship for years, always feeling that she should stay for the children's sake.

"One night, I'd had enough," Jacobs says. "I couldn't stand to hear him shouting at the kids any more, so I put them in the back of the car with as many clothes as I could stuff into a suitcase and drove for 22 hours non-stop all the way from Umbria, where we lived, to London, to my Mum's place." Jacobs was so desperate to escape her husband that she abandoned the jointly owned family home and is unlikely to see any profit from its future sale. She has also had to leave behind a life she spent more than a decade creating. "My vegetable garden, the dogs, chickens, everything. It's pretty devastating," she says.

Jacobs is a pretty, smiling woman, hyper-capable and always upbeat, so it seems terrible to see her brought so low. But then she looks up from her coffee, grins and says: "I know it sounds weird, but it's such a relief. I'm so happy!"

This post-separation joy is a common, almost ubiquitous theme. It is deeply frightening to contemplate separation and divorce, so it is extremely rare to consider it at all unless you already know for sure that it is the right thing to do, both for you and for the children. We all know the stigmas attached to divorce, we have heard the horror stories about abusive fathers who abduct and succeed in keeping the children, and we know about the huge financial cost. We know most children would prefer their parents to stay together. We have the information, so we wouldn't be thinking about divorce at all unless in our heart of hearts we were sure we'd be happier afterwards. Children are surely better off with divorced happy parents than with miserable married ones.

I spoke to a divorced Iraqi man who, in separating from his wife, had lost both his home and children. He lives alone in a rented flat and sees his children once a week and every other weekend. He described the end of his marriage as being like the end of communism - a dream that had seemed idyllic, that everyone pretended was idyllic, but that was fundamentally rotten at its hidden core. "Was it better before?" he asks, thinking of family meals, holidays and the simplicity of coming home to his children. "Yes," he concludes. "But do I want it back?" he wonders, thinking of the tension, the unspoken animosity, the pressure of constantly pretending. "No."

Another important question from Kirshenbaum: "Think about that time when things between you and your partner were at their best. Looking back, would you now say that things were very good between you?"

The expectations of happy marriage and blissful family life that pervade international culture can be deceptive. We often convince ourselves that we are happier, better suited to a particular person than we really are and then, aware that things are not as they should be, plough on regardless. Nobody is trying to pretend that marriage is easy - of course, all long-term relationships will go through good and bad phases, will need to be stuck at through adversity and may almost crumble but be saved by one or the other partner's determination. But that doesn't mean we should stay when we really ought to go.

Samantha Timoney, a 46- year-old mother of two in London, knew she had to go when she had a breast cancer scare.

"I found a lump and the doctor wanted to do a biopsy. I went to hospital by myself and I'd spent the whole day crying. When I got home my husband had forgotten that this was the day of my biopsy. He told me he was feeling low and when I reminded him what had happened that day he just shrugged. I realised that although he's a wonderful dad to the girls, he just doesn't care about me at all. I could stay and know that forever, or I could go. I decided to go."

Plenty of Emiratis are going, too. Figures released by the United Nations show the UAE has one of the highest rates of divorce in the Muslim world, at 46 per cent, and the highest among the Gulf Cooperation Council countries, with the divorce rate in Qatar being 38 per cent, 35 per cent in Kuwait and 34 per cent in Bahrain. Of these divorcing couples 42 per cent are in their 20s.

Set these figures against those of the US, where the divorce rate is still the highest in the world. Fifty percent of first US marriages end in divorce and 67 per cent of second marriages dissolve.

Fatma Sayegh, a professor specialising in woman's issues at UAE University in Al Ain, says many of the problems plaguing marriages in the country could be addressed by better preparing couples. Sayegh, who has conducted several studies on divorce in the UAE, says many couples marry too young.

"Many young people are not taking marriage seriously," she says. "That's why after two or three months many take a divorce. There has to be more awareness that marriage is not just a wedding, a party and white gowns."

In a paper on the rising divorce rate, Najla Al Awadhi, deputy CEO of Dubai Media Incorporated and general manager of Dubai One TV, blames rapid socio-economic changes for creating a metamorphosis in the landscape of society. Chief among those changes is the rise of education for woman.

"An educated woman is no longer solely dependent on her husband," writes Al Awadhi, "she has access to work opportunities, and she has a strong mind, allowing her to decide what type of life she wants to live. In my grandmother's generation, this was not the case. Most women were illiterate, they had no understanding of the rights Islam had granted them, let alone any grasp of how to practise these rights, or how to survive independently."

For, while often severely stigmatised, divorce is permitted in Islamic culture, though Sharia can make it difficult unless the judge is convinced that divorce is the right course of action. A woman may be granted a divorce if she can prove that her husband has physically hurt her or mentally tortured her. A woman also may sue for divorce if her husband abandons her for a period of three months, or if he has not taken care of her needs or those of the children.

Alessandas Picchi, who lives in Dubai, has been divorced three times and is about to wed for the fourth time, in a chapel in Las Vegas.

"You have to be married here in the UAE," she says. "You are not allowed to live with someone unless you are married. So, we're getting married. I suppose I'm just romantic and I always hope he's the one. I haven't managed to have children, but I always get to keep the cat."

So, is rising divorce simply a price society must pay for the sudden affluence bestowed on the Emirates by its oil and gas riches? "Is it the contagion of more liberal attitudes absorbed from the large numbers of western expatriates and their television soaps?" asks Widad Samawi, director of the Tawasel centre, coordinating the National Campaign for Social Cohesion and offering marriage counselling in the UAE. "Some couples like to imitate what is going on in the media. They have their dreams, but when they start married life they face the reality. Say the wife is fond of a character in a TV show, she wants to imitate the actress, but she can't do this without annoying her partner."

There is also the effect known as "divorce clustering", the effect of one couple divorcing giving the green light to their friends who might have been considering separation but hadn't dared to do it. A friend's divorce can reduce the social stigma of splitting up, even when children are involved, say findings from a continuing US study. The researchers, led by Rose McDermott of Brown University, Rhode Island, found that every divorce sends ripples through friends, families and work colleagues.

"The full network shows that participants are 75 per cent more likely to be divorced if a person they are directly connected to is divorced," says McDermott. "The size of the effect for people at two degrees of separation - for example, the friend of a friend - is 33 per cent. At three degrees the effect disappears."

But is this a bad thing? Divorce tends to be portrayed in a fear-mongering way by the media in all countries, but, for many women, the ability to separate from an unsuccessful relationship is a sign of liberation from suffocating cultural constraints that force them to put up with misery and abuse. At last, women have more choice about whether to get or stay married, more choice about whether to live alone, with friends or in a relationship.

"It's hard having to work and look after the children, but it's fantastic to come home to a place that's mine where nobody hates me," says Jacobs. "I'm free and I'd rather be alone forever than have stayed with a man like that."

"Women's financial independence makes them more willing to accept divorce rather than live an unhappy life," agrees Madiha Al Safty, a sociology professor at the American University in Cairo.

But an Arab divorcee may still have a lot to cope with. "Society's attitude toward divorced women may have changed slightly, but people still have a predisposition to stigmatise female divorcees," says Madiha Al Ajroush, a Saudi psychologist. "When a woman becomes a divorcee, her social status is downgraded, her personal freedom is limited, and her rights as a mother may be taken away. Young unmarried women have more freedom than divorced women."

Tony Maalouli, a divorce lawyer who has worked in Dubai for eight years, believes the footprint of foreign cultures, has affected the traditions of a conservative country.

"It's a more open society here," he says. "It's a melting pot for different cultures, and Emiratis are exposed to other cultures. I am not saying there is anything wrong with these cultures, but the rate of divorce in these countries is high. These countries leave their effect on the UAE and the lifestyle."

So, whether divorce is a western plague or a liberating possibility, ask yourself one last Kirshenbaum question:

"In spite of admirable qualities, and stepping back from any temporary anger or disappointment, do you genuinely like your partner, and does your partner seem to like you?" And will this ever change even if you die married? You already know the answer.

Should I stay or should I go? One woman's tale of the effects of an affair on her marriage

Once upon a time, I met a man who made me very happy. I experienced an elation I had never felt with anyone else in my life. Within three and a half years of meeting, we were married with baby number one. That was five years ago.

After I returned to work things went downhill. Suddenly it was not the meeting of two independent people choosing to live together. His life continued as it always did. I had worked throughout pregnancy, taken minimal maternity leave to show willing, was given a new role which required longer hours; I had no sleep and insufficient childcare. I couldn't cope and I fell into a black hole mentally.

As it turns out, around this time, my husband started having an affair. She was single, could easily look after herself and gave my husband attention. I was on my last legs, wiped out and unable to hold house, me and work together.

I didn't know what had happened to us. He ignored me and didn't talk. He loved the baby, but closed me off. I was desperately lonely and destroyed inside but work helped me to carry on.

I didn't know couples could be happy after a baby was born. I felt sorry for anyone who was pregnant as I thought, alas, their marriage would decay just as mine had.

I accepted the situation as part of the downward spiral of every marriage that I could see, and we had a second baby. At the time I felt like I was going mad. My husband told me I was depressed and arranged counselling for me. I admit a terrible thing - I regretted for a time having our first baby as without a doubt it destroyed our marriage, which had been a fantastic one before that.

I found out about the affair through anonymous texts from the other woman. I felt like I was in the middle of an earthquake in my head. Slowly, painfully. facts came forth. The deception was catastrophic. But another feeling was relief. He had told me I was depressed and I felt like I was going insane. I knew at that point it was his fault. That I was OK.

A few months after I found out, I was made redundant, and he was promoted. We worked for the same company, so it was doubly painful. I know my lack of drive at work due to low self-esteem and having babies was a factor, even if they would never admit that.

I still think about the affair every single day. When it ended physically for him, the gamut of emotions only just began for me.

My self-confidence is still in tatters. The pain is so raw due to the shock and unexpectedness. I was helpless: two young children and no job, and forced to contemplate staying with someone who had hurt me more than anyone else in my whole life.

How do you rebuild? You only consider this of course for the children. Your gut instinct is to run, run far away, hide and cry. Then make a new life without ever looking back. But this is impossible when you have children. You are utterly tied.

Trust is the backbone. The lies hurt as much as the rest. How long do you give another to prove trust? Especially when the other woman continues to contact them "as a friend"?

The man I married sent me to the deepest pit of depression, turned me into a spy in my own home to protect myself; I still have panic attacks, tears and anger... The symptoms post-affair are recognised as being similar to post-traumatic stress disorder. The landscape of what I believed turned out to be false. How many years will it take for me to recover?

In January I decided that I simply couldn't take it anymore and threatened to leave him. The continued lack of trust had eaten away at my health and I still suffer from panic attacks. My New Year's resolution was to be happy.

Finally, he took notice. For three months now he has been a good husband. We have been getting on well. Family life has been lovely. Nobody knows me like he does.

Why am I still here? For a long time I thought it was because I couldn't cope alone. I didn't want to bring up the girls alone - why should I suffer because of his errors? It wasn't fair on them or me.

Now it's not just that. We are good companions. We live well together and hold similar outlooks. And most importantly there is a shared history and two little children.

I have not yet decided what to do and yet again he has won. I gave him far too long and too many chances to prove himself to me. He took years of my life away where I was deeply unhappy.

When I look at our baby photos I nearly cry as I think of what he was doing at the time. I am sad to think I have not had one baby where he wasn't having an affair with another woman.

My focus now is not on the marriage. I care less. I have been so hurt that I am numb to a great degree. Trust was always the most critical thing to me as I believe that is the key to great relationships. That was broken in the most awful way. I won't ever get over that pain but as with everything, pain decays with time.

So, the landscape of my life has altered. Everything that I believed was not true for a long time. I respect him less. But this life is the best life for me at the moment.

Of course I would never stay with someone who did that to me if I had no children, but I don't have an equal choice. I also know no man that would tolerate what he did to me. But women have to decide what is best for a unit sometimes.

Should I stay or should I go? To stay - a sacrifice against what I believe in is right, for the greater good of a new and innocent family. To go - risk all security and a shared family history? As I keep telling my friends, it's OK for now.

My aim is to become independent once more. At least if I were financially independent I could make a real choice. But I can never run away and forget - he is the father of my children.

My mother, who experienced a similar thing and had no choice to leave, said you never get over it. You never care in the same way again. For a while, sometimes forever, your emotions are numb and you are spent. Like a turtle, you shield your heart to defend from the next attack.

I often wonder what I should suggest to my daughters about marriage. I think it is one of the most vulnerable positions a woman ever commits to.

As told to Helena Frith Powell