India’s push to become a hub for semiconductor manufacturing is under way — but there is still a long way to go. It will have to try to catch up with countries already well-established in the sector, analysts say.

The South Asian country's ambitions took a major leap forward this month, with the announcement of Indian mining company Vedanta and Taiwan’s Foxconn developing a semiconductor manufacturing plant, one of the country’s first, in the state of Gujarat.

The two companies intend to invest 1.54 trillion rupees ($19 billion) in the complex.

“That is a very positive development — the government of India has tried to get investment in this space for a long time,” said Subhabrata Sengupta, executive director of Avalon Consulting, a strategy and management consulting company.

“Now the question is execution and if this will spur development of [an] ecosystem like Taiwan.”

Obstacles include the huge amounts of investment needed to set up chip manufacturing plants and India's newness to the industry, he added.

Taiwan is by far the world’s largest producer of semiconductors. Its contract chip makers are projected to account for 66 per cent of the global market share by revenue this year, up 2 percentage points on the previous year, data from market research firm TrendForce showed.

South Korea and China are also important countries in the global semiconductor supply chain.

The chips play an essential role in products such as smartphones and electric cars.

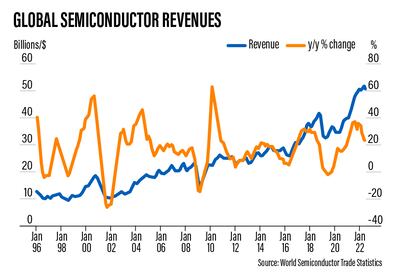

With demand for such goods growing, the worldwide sales of semiconductors reached $152.5bn in the second quarter of 2022. This was up 13.3 per cent on the same period last year, the Semiconductor Industry Association said.

India is eager to secure a slice of the growing market, and to that end, Prime Minister Narendra Modi's government has set out its ambitions to become a hub for chip production.

To accelerate its plans, India unveiled a $10bn incentive programme for semiconductor and display manufacturers in December last year. The idea is to attract global manufacturers, to bring in much-needed know-how, and to generate opportunities for local companies.

The Indian government also sees indigenous chip manufacturing as essential to its plans to massively scale up the country's electronics manufacturing industry, as part of its “Make in India” initiative.

During the Covid-19 pandemic, as demand for electronics surged amid supply chain disruptions, the challenges highlighted the benefits of local semiconductor production. Electronics and car manufacturers in India — and globally — had production disrupted by the shortages.

“Industries have been suffering due to the global shortage of semiconductor chips,” said Sanjay Kumar Kalirona, chief executive and co-founder of Gizmore, a smart accessories and audio brand.

“India is well poised to make the most of the situation at hand."

He added that local manufacturing of semiconductors would "help in overcoming the supply chain issues" that India had to face ― and that there could also be some "cost advantages" for the sector.

The global semiconductor manufacturing market is set to more than double in this decade to $1tn by 2030. India has an opportunity to grab about $80bn of the market, forecasts a report released earlier this year by the India Electronics and Semiconductor Association.

“Going forward, with the Indian government’s additional focus on building an overall ecosystem for semiconductors in the country, the country will witness a rapidly expanding electronics manufacturing and innovation ecosystem,” Counterpoint Research said on September 16.

“By doing so, it does not only aim to become an important destination for manufacturers and investors, but also ensure its strategic position in the global value chain.”

Backed by the chip manufacturing push by the government, plans for the sector are starting to take shape.

In May, the Karnataka state government — in the south of the country — said it had signed a preliminary agreement with international semiconductor consortium, ISMC to set up a semiconductor fabrication unit. ISMC is a joint venture between Next Orbit Ventures in Abu Dhabi and Israel's Tower Semiconductor, which was acquired by US chip major Intel.

The state government said that the consortium would invest $3bn in the plant.

In July last year, Singapore-based IGSS Ventures said that it had signed an initial pact with the state government in Tamil Nadu in India to develop a 300-acre “semiconductor high-tech park”.

IGSS group chief executive Raj Kumar described India as “a late starter”, at the time. “We are confident that this strategic approach moves India towards taking its rightful place as a competitive, alternative semiconductor destination,” he said.

The biggest announcement to date, however, has been Vedanta and Foxconn's plans to set up a semiconductor and display plant in Gujarat. Vedanta chairman Anil Agarwal on Twitter noted that “India's own Silicon Valley is a step closer now”.

“India will fulfil the digital needs of not just her people, but also those from across the seas,” he tweeted. “The journey from being a chip taker to a chip maker has officially begun.”

chief executive and co-founder of Gizmore

The neighbouring state of Maharashtra, of which Mumbai is the capital, had also been competing for the opportunity in the sector, which brings a host of economic benefits.

The new plant, which the companies aim to have operational in 2024, is projected to generate nearly 100,000 jobs.

“We are determined to make our country more self-sufficient in tech and curb our reliance on imports from other countries,” said Gujarat's chief minister Bhupendrabhai Patel when announcing the deal.

“We hope that the hub will be the beginning of a bright future and attract investment from other multinational companies down the line.”

Brian Ho, vice president of Foxconn Semiconductor Group, said that “the improving infrastructure and the government's active and strong support increases confidence in setting up a semiconductor factory”.

However, it is still very early days. With India being so new to the sector, there are a number of hurdles that the country still needs to overcome before it can become a major part of the chip-making supply chain.

India's semiconductor manufacturing to date has largely been centred on production for its state-controlled defence and space sectors.

“It is critical that the government and industry together create a robust and indigenous technology ecosystem for India's semiconductors industry's success,” said Saket Gaurav, chairman and managing director of Elista, an electronics, home appliances and IT brand in India. But he is hopeful that India could eventually emerge as one of the largest chip makers in the world.

With the commercial industry being in its very initial stages in the country, this means that there is a “lack of ecosystem and experience”, Mr Sengupta said.

“India has a large pool of engineers working in semiconductor industry all over the world” and there is “an opportunity to attract that talent back”, he pointed out.

Meanwhile, access to raw materials and water supply is among other considerations to factor in, industry insiders say.

India's efforts to become a semiconductor hub comes as the US and the EU are also focusing on scaling up their chip manufacturing industries. But experts say that there are still gaps to be filled.

The US, under the previous Donald Trump administration, started cutting off China's access to American technology, including chip-making equipment. Next month, the Biden administration plans to widen curbs on shipments to China of chip-making tools and semiconductors used in artificial intelligence from the US, a Reuters report said.

“Crucially, via deals like [the Vedanta-Foxconn plant], India may be able to reduce the world's dependency on China,” Mr Kalirona of Gizmore said.

He added that the move showed that the Indian government was helping “to move the needle in the right direction”.

“We believe that the Foxconn-Vedanta deal will be one of the many in the space and there will be many more to come,” Mr Kalirona said.