Pop quiz: name an internet company, at least 10 years old, that does only one thing.

It’s hard to come up with many examples, isn’t it?

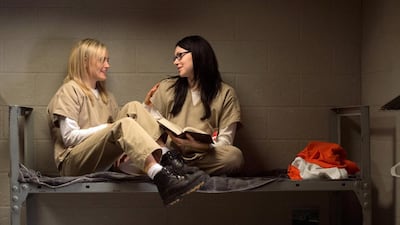

That’s precisely why Netflix, which will celebrate a decade of streaming next year, is eventually going to have to sell something besides video-on-demand subscriptions.

The veritable writing hit the wall this week with the news that Amazon will offer its existing video service as a standalone product in the United States. So far it has been bundled with Prime, the company’s expedited shipping service, for US$99 a year.

Amazon Video, which streams TV shows, movies and award-winning original content including Transparent and Mozart of the Jungle, will be available for $8.99 a month, or $1 less than Netflix’s most popular tier.

If it wasn’t already, Amazon is suddenly Netflix’s most dangerous competitor.

The two companies are battling for US subscribers, and with that, the licensing rights to TV shows and movies. Both are also spending big to create original films and series to differentiate from each other. Netflix is investing $5 billion this year in original content, while Amazon is spending an estimated $4 billion.

Netflix is available in nearly 200 countries, including the UAE, but the importance of the US market to the company can’t be overstated. Nearly two-thirds of its 69 million subscribers are there.

The problem for the company is that it has nothing else to offer customers. Amazon, often referred to as the “everything store”, has plenty. On the internet, that diversity matters.

Successive internet companies big and small have learned this important lesson over the relatively short history of the medium: it’s not enough to do one thing, because it’s easy for competitors to come along and match it or even improve on it.

The key to online survival and growth is to therefore expand into a variety of products and services that hook customers into an ecosystem, which makes it harder for them to defect to a competitor.

Google and Apple have mastered it with phones, maps, apps, music, cloud storage and a host of other products. Amazon has done it too, with books, e-readers, tablets, music, cloud hosting, groceries and pretty much every other retail item imaginable.

Facebook is also there, with status updates and the ability to share photos merely the first arrows in a quiver that now includes private messaging and virtual reality. Various forms of artificial intelligence and drone-based internet access are in the works.

Even Uber, the ride-sharing company that is barely seven years old, is already diversifying by expanding into food and parcel delivery.

Single-purpose companies often end up getting purchased by these big powers, where they’re added to the veritable quiver - see YouTube or Instagram. The other likely scenario is they falter and fade away. Music streaming services, such as the defunct Rdio and the reportedly up-for-sale Pandora, are currently learning this the hard way.

Aside from Amazon in the US, Netflix is also facing rapidly advancing competition around the world. In some cases, its rivals are also multi-tooled players.

In Australia and Canada, for example, the company is facing competing streaming services owned by large media and telecom conglomerates. Like Amazon, the companies can offer subscribers a bundle of services - say, a discount on internet access here, or a deal on wireless service there.

In the long run, they hold competitive advantages over Netflix.

In an interview at the Consumer Electronics Show in January, the Netflix chief executive Reed Hastings played down the likelihood of Netflix expanding beyond video, stressing the importance of being really good at just one thing.

“Companies that have great propositions sell those propositions independently,” he said. “But companies that have weak propositions, or maybe they just have other strengths, they just try to combine them.”

Yet, Netflix’s rivals - whether Amazon or others - are quickly catching up, to the point where their weaknesses aren’t as obvious anymore. Their improving services are likely a major factor behind the cooling subscriber growth that Netflix announced on Monday, which led to a tumble in its share price.

The pressure is mounting for Netflix to start thinking about something besides just streaming. Either that or the unthinkable could happen, where the company ends up as an arrow in somebody else’s quiver.

Peter Nowak is a veteran technology writer and the author of Humans 3.0: The Upgrading of the Species.