Ask any football fan where he'd most like to watch a World Cup and there's a pretty good chance he'll say Brazil, the spiritual home of the beautiful game.

So while there may not be a lot of reason to give credit to Fifa, it deserves a modicum of thanks for choosing Brazil to host the 2014 World Cup.

Now, though, the ball is in Brazil's court and it's struggling to serve up anything like the stadiums, infrastructure, security and accommodation necessary to meet the needs of such a huge event.

"I must say that in comparison with the state of play between South Africa and Brazil three years before the World Cup, Brazil is behind South Africa," Sepp Blatter, the Fifa president, warned last month.

The World Cup is "tomorrow", Blatter added. "The Brazilians think it's just the day after tomorrow. What they must do is to give a little bit more speed now in the organisation."

Speed and organisation are exactly the two things that Brazil lacks. It's been more than three years since it was awarded the tournament, but no stadiums have yet been built. In fact, it took Blatter and Ricardo Teixeira, the president of the Brazilian Football Confederation, more than a year just to decide the host cities. When they did, they chose 12, more than is usual, because they wanted to please as many people as possible.

In two of those cities, Natal and Sao Paulo, work on the stadiums has yet to begin. Natal runs a serious risk of being dropped from the schedule, and the country's sports minister has already suggested the number of venues could be reduced to eight.

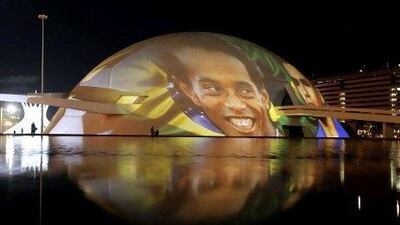

In other cities, costs are nonsensical or have spiralled out of control. The modernisation of the legendary Maracana stadium in Rio de Janeiro, where the World Cup Final will be held, will exceed US$600 million (Dh2.2 billion) when added to the improvements carried out over the past few years. Manaus is spending more than $300m on a new stadium even though its biggest club is in the fourth division. And in Brasilia, authorities are paying almost $445m to upgrade the Mane Garrincha stadium but did not insist that a new pitch be included in the cost.

The problems in Sao Paulo are even more emblematic of Blatter's and Teixeira's pettiness and inability to get their act together. The city is Brazil's largest and most important, and three of its stadiums are regularly used for first division football.

The biggest is Morumbi, home to Sao Paulo football club. The 80,000-capacity Morumbi was originally supposed to host the opening match, but Teixeira ruled it out after a series of personal disagreements with club officials. Corinthians, whose president is a friend of Teixeira, were asked to step in and help.

The problem is that Corinthians don't have a stadium. The club hastily produced a plan to build one but with less than the 65,000 capacity Fifa demands for the opening match. Corinthians said they would install 17,000 temporary seats. But still no work has begun and the clock is ticking. Neither that stadium nor the Maracana will be ready for the 2013 Confederations Cup that serves as a test run for the real competition a year later.

While all this is worrying, of more lasting concern to many Brazilians is the surrounding infrastructure. The country desperately needs roads, ports, airports, rail links and hotels, not just to handle the proposed influx of 600,000 visitors but simply to cope with the fast-growing economy.

Successive governments failed to invest and the results are plain. There are not enough hotel rooms. Security is still a major issue. The motorway network outside the richest states is often little more than cratered tracks. There are almost no intercity rail links, and urban public transport is inadequate and substandard.

But the biggest concern is airports, which are in such a run-down state that Pele called them "frightening".

Work is under way to modernise 13 airports, but as with the stadiums, the effort is late and poorly planned. Even without factoring in World Cup traffic, passenger capacity is estimated to go from 86.1 million today to 143.3 million in 2014, and yet authorities were so slow to get the builders in they no longer have time to put up new structures. In several airports, tourists will be greeted by temporary modules.

"Airports are already unable to meet current demand, and that is our biggest issue," said Jose Roberto Bernasconi, the author of a progress report on the construction work. "We are now seeing the consequences of them not doing what they could have done."

Mr Bernasconi's biggest fear is not that the stadiums won't be ready, or that the World Cup will be a disaster. With a great climate, myriad tourist options, vibrant nightlife and a population that is both friendly and football mad, Brazil has all the ingredients to host the most memorable World Cup ever.

The fear is the lack of a legacy. Unless it gets moving, and very quickly, Brazil will have nothing more than memories once the final whistle goes and the fans head home.

"We want the World Cup, but more than that we want to transform the country's infrastructure in the name of the cup," said Mr Bernasconi. "We want a legacy."

Brazilians deserve that. At the very least.

* Shoba Narayan is away