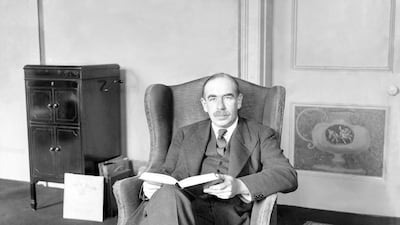

The Great Recession has overturned economic theories and their proponents as comprehensively as it has jinxed the world’s money markets. Commentators, academics and authors all puzzled by the failure of current economic models to predict the crisis of 2008 have looked back to the Great Depression to find answers. With the death of the global free market, one man’s reputation for sound thinking has been resurrected, that of the British economist John Maynard Keynes.

Keynes’s path-breaking economic theories made him almost a household name during the interwar years. He formulated them at a time of massive unemployment, overturning received wisdom about free markets, advocating government stimulus.

Keynes has not lacked for biographers – Robert Skidelsky’s three definitive volumes have taken their place in the canon of great modern biographies. Thus the appearance of Richard Davenport-Hines’s Universal Man: The Seven Lives of John Maynard Keynes would seem to be something of a puzzle. Does Keynes need another biographical write-up? Davenport-Hines does a fine job convincing you he does.

This new book is modest in its aims, but trenchant in its effects. Davenport-Hines conjures the essence of Keynes not by a cradle-to-grave treatment. Instead, he rearranges the components of Keynes’s life into seven categories. There are chapters on Keynes as the altruist, boy prodigy, official, public man, husband and lover, connoisseur and envoy. Davenport-Hines depicts Keynes as a man of multitudes.

The first chapter sets the tone: Davenport-Hines casts Keynes as a crusading optimist who sought to remedy the problems of capitalism and thus allow individuals to flourish. “He seems – more than ever – an inspiring example of an intellectual who was bold in his ideas and unselfish in the ways he put them into action,” Davenport-Hines writes. “If his life has one pre-eminent lesson, based not on wish-washy hopes about human nature but on probabilities for good outcomes, it is that if confronted by conflicting alternatives, when choosing the way forward in practical matters, the sound principle is to take the most generous course.”

Keynes’s genius showed itself at a young age. His economist father and pioneering mother doted on him and encouraged his pursuits at Eton and then King’s College, Cambridge. His university experience would affect him profoundly. It was here he met Lytton Strachey, Leonard Woolf and other members of the Bloomsbury Group, who formed the Apostles, a secretive club. “The personal importance of individual Apostles, and of the Apostolic circle, to his thinking, choices and actions cannot be overstated,” Davenport-Hines observes.

Under the influence of philosopher G E Moore, Keynes learnt to flout conventions. “We claimed the right to judge every individual case on its merits, and the wisdom, experience and self-control to do so successfully.” Keynes was nothing if not confident.

Though he’s not an economist, Davenport-Hines proves a fine guide to the development of Keynes’s theories. As a young man, Keynes worked at the India Office, then the Treasury, which brought him to Paris in 1919 as the Allies hammered out the settlement after the First World War. He resigned his position, and had his first brush with fame, upon the publication of The Economic Consequences of the Peace, a scathing dissection of Allied aims. Keynes criticised the punitive reparations placed on Germany at Versailles. The behaviour of the politicians at the bargaining table appalled him. It was here that Keynes began to develop a technocratic vision. As Davenport-Hines observes: “Implicitly he proposed technical experts, with economists foremost, as a new brand of world leader, beyond the clutches of traditional party politics, vote-buying and tribal loyalties. ”

Economics can be a notoriously arcane discipline, but Keynes was a superb communicator whose views were published in leading magazines and journals. He opposed socialism and Bolshevism, and promoted Liberal Party policies, though he did not run for office himself. (“Keynes was a patrician in outlook. He suspected that liberty was incompatible with equality, and had a sharp preference for liberty over the chimera of equality,” the author writes of Keynes’s political sensibilities.) He was preoccupied with the failure of government policies that failed to get the economy going. “Negation, restriction, inactivity – these are the government’s watchwords,” Keynes wrote in 1929 ahead of a general election. “Under their leadership we have been forced to button up our waistcoats and compress our lungs. Fears and doubts and hypochondriac precautions are keeping us muffled up indoors. But we are not tottering up to our graves. We are healthy children. We need the breath of life.”

Such brash optimism informed Keynes’s economic writings. High unemployment would not simply go away without some kind of government action to stoke consumer demand and encourage investment and employment. It is arguable whether Keynes himself was a “Keynesian” – it was for a later generation of economists to extrapolate from The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money, his great work of the 1930s. Davenport-Hines devotes only a few pages to this difficult treatise, “one of the most influential works of economic thought, and arguably the most intellectually audacious, ever published”.

But the intent of Universal Man is to show all of Keynes’s facets, not just Keynes the economist. The chapter on Keynes as lover tactfully explores his private life. Though he was essentially homosexual – he had many escapades with men – in 1925 he married the Russian ballet dancer Lydia Lopokova. Their marriage was quite successful, and Keynes was devoted to her. He was also a lover of the arts whose friends included Virginia Woolf and other writers.

Davenport-Hines ably justifies his approach, arguing Keynes’s many sides are complementary: “An abiding concern for him was how civilised people could use their time and abilities well, and fulfil themselves in virtuous, responsible, productive lives. All his intuitions, expertise, priorities and advice revolved around these quandaries. His lives as an economist, as an official, as a pundit, as a lover, as a patron of creativity, as a Londoner and latterly as a country gentleman might seem to be sealed in distant compartments; but they were indivisible in their ethical underpinning.”

The Second World War would see Keynes return as a government envoy. He worked tirelessly to negotiate American loans that buttressed the British war effort. He took his public duties seriously, but his wrangles with American officials proved taxing. He also pondered the shape the postwar world might take. “From the autumn of 1941, Keynes worked at creating a postwar global capitalist economy that avoided the instabilities, fluctuations, excesses and failures of the pre-war system.” Here were the origins of the World Bank and International Monetary Fund, institutions that bear Keynes’s imprint. Davenport-Hines movingly writes of this last phase of Keynes’s life – he would die in 1946 – “with altruism in his heart he chose to dissipate the last remnants of his strength in public service”.

What would Keynes make of theories that today bear his name? Impossible to know; but Davenport-Hines notes, “he was after all, both brilliant and brave in having second thoughts. He did not believe in mental standstills”. However much Keynes’s ideas have been refined, revised and criticised by subsequent generations, his ceaseless activity and willingness to think boldly remain an inspiration.

Matthew Price is a regular contributor to The National.