Today the world still grapples with the convulsions of the First World War. This far-reaching legacy, across literature, borders and politics was the subject of a day long event at Paris Sorbonne University Abu Dhabi during the week.

The series of talks, to mark the 96th anniversary of the day the guns fell silent, addressed themes of remembrance but also examined how the First World War has shaped the world today.

First up was literature – the writers of the war have in many ways defined the conflict.

According to Vital Rambaud, head of the French studies department at the university, the war mobilised an entire generation of French writers, and more than 500 never came back.

“We will never know what masterpieces the war deprived us of,” said Rambaud, who gave the first talk on the literary consequences of the First World War.

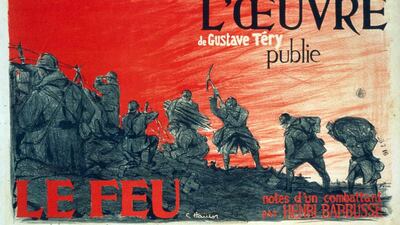

But despite this, several war novels and writings won the prestigious Prix Goncourt during the war years. Henri Barbusse's Under Fire, for example, a gritty portrayal of life on the Western Front, won in 1916.

“The war helped develop a literature of peace, replacing the heroic model of military stories which had prevailed in the 18th and 19th centuries,” he said.

But the conflict also transformed soldiers into writers – this was a literary war. They wrote letters, postcards, memoirs and journals to recount their experiences. “This was a historic heritage that families have preserved,” Rambaud said.

There was also a partial mobilisation of writers to wage a textual propaganda war supporting France’s efforts in the conflict.

For example, Maurice Barrès was transformed from writer into war journalist, writing patriotic articles promoting the spirit of France. Barrès was a proponent of the Union Sacrée, which earned him the scorn of the satirical press.

“In the wake of the war, the pre-1914 masters lost their audience. Literature after the war could never be the same again,” said Rambaud.

Another lecture dealt with a topic more pertinent to those of us living in the Arabian Gulf – the consequences of the war in the Middle East. This sought to examine the break-up of the Ottoman Empire after the war, Kurdish demands for their own country and the attempt by ISIL to establish a state with utter disregard for established borders.

The Kurdish fighters, the Peshmerga, are leading the international fight against ISIL on the ground and TV images of their resistance, especially in Kobani, have been beamed across the world. “Their engagement against such a menace [ISIL] and the media focus on the battle in Kobani allows us to recognise the Kurds and their aims,” said Professor Anne-Claire Bonneville, of the French National Institute of Oriental Languages and Civilisations.

But while it is a positive moment for the Kurds, states such as Turkey, Syria and Iran are not happy. “Turkey seems to be just as determined, like it was during World War I, to thwart any attempt at creating a Kurdish national entity,” Bonneville said.

The Middle East was a secondary front, but the fallout from the war creates conflict today. It is the rise of jihadists, chiefly ISIL, that are the most real manifestation of this. “Beyond commemorations and remembrance, we can only but witness how the map of the Middle East designed by the French and the British a hundred years ago has been shaken by the political forces trying to redesign it.”

A third lecture told the intriguing story of a Dominican priest, Antonin Jaussen, who became an unlikely figure in the intelligence war. His knowledge of Bedouin dialects and customs led him to being hired by the British and French. Jaussen is known for having warned the British in 1915 of an imminent attack on the Suez Canal. “He became an actor in the great history,” said Professor J J Pérennes, of the Cairo Institute of Middle East Studies. “It justifies why he still is cited in the same areas he passed through a hundred years later.”