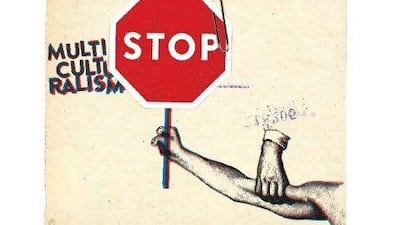

Britain's soft-spoken prime minister is in combative mood. Flexing his political biceps, David Cameron is itching for a fight with Muslims and foreigners.

A week ago he introduced the phrase "muscular liberalism" into the political lexicon, though without providing much definition.

Asserting that Muslim groups were ambiguous about what he called "British" values of democracy and equal rights (a claim the Greeks might question), Mr Cameron said: "We need a lot less of the passive tolerance of recent years and much more active, muscular liberalism."

For Mr Cameron, searching for a big idea to define his premiership, muscular liberalism is a solution to two very different problems: how to forge a strong national identity in an age of globalisation and how to find a role for the UK in a world where British power is declining.

Most media reports of his speech, made at a European security conference in Munich, Germany, emphasised the first of those points. Mr Cameron focused on the Muslim minority in Britain and his perception of its integration challenges. He then made a logical leap to arguing that the challenge of integrating some communities in Britain poses security questions.

It does no such thing. There are many communities in Britain, only a small number of them Muslim, that face challenges integrating. Those questions are not limited to certain ethnic or religious groups. They are, first and foremost, related to economic factors. That is why, in an unequal country like Britain, sections of society are disenfranchised.

Take the large number of young white Britons who have been brought up without opportunity, on estates with few people in employment. For these people - there are families where two or more generations have never known regular paid work - the glittering material rewards of the West are a dream, an apparition.

These groups are not part of the British mainstream and their difficulties fitting into the wider society have nothing to do with differing ideas of democracy or equal rights, as Mr Cameron suggested. These groups are not held back by religion or culture. They are held back by socio-economic factors.

The challenges of multiculturalism are not challenges borne only by the Pakistani, Indian and Bangladeshi communities that make up the bulk of Britain's Muslims. They are borne by many groups, including poor white communities and poor black communities.

It was David Cameron's predecessors in 10 Downing Street who decimated the opportunities of working people in Britain, consigning large numbers - white and black and brown, Muslim and Catholics and Protestant - to unemployment. The ills of globalisation have fallen on many shoulders.

On the day Mr Cameron delivered his speech, a significant far-right demonstration took place on the streets of Luton, an English city.

Mr Cameron is posturing to a constituency, within his party and the country, that is hostile to immigration and to Islam. He is trying to convince them, with a wink and a nod, that he feels their pain.

It is no surprise that supporters of the self-styled English Defence League, the far-right British National Party and its more organised French counterpart, the National Front, all welcomed Mr Cameron's comments as a recognition of their ideas by the establishment.

Mr Cameron offered no new help, no new policies, no new ways of navigating a rapidly changing Britain. To the very real challenges of integration and the economy, Mr Cameron's muscular liberalism has no new answers, only worn clichés.

The other problem Mr Cameron's "muscular liberalism" seeks to solve is a far broader one. Britain is no longer the world power it was even 50 years ago. Its closest ally, the United States, is no longer the sole pole of power. World power is shifting eastward.

Mr Cameron knows this, but is unsure what to do about it. His predecessor, Tony Blair, tried to hitch his wagon to America's, while also trying to lead in Europe. But the past decade has not been kind to US power and the financial crisis has exposed serious flaws with the Anglo-American economic model. In Europe it is Germany, not Britain, that is showing the Continent a route out of recession.

Mr Cameron's strategy of exporting "British" values is fatally flawed by a lack of muscle to translate his words into reality. He is hamstrung by two chief issues, one domestic, one international. Domestically, he is not the captain of his own ship: as prime minister, he has a coalition partner party that is much further to the left than most of his Tories.

On foreign policy issues, the Liberal Democrats and the Conservatives have widely divergent views. In July, Nick Clegg, the deputy prime minister and leader of the Liberal Democrats, called the 2003 invasion of Iraq - a war the Conservatives and David Cameron personally supported - illegal. He was later forced to clarify that those were his "personal" views.

Internationally, Britain no longer has the clout to decide unilaterally what other countries do, nor even to choose which countries it will work with.

In his speech, Mr Cameron referred to Egypt, saying his government wanted to see a free and democratic society in Egypt. "I simply don't accept that there's a dead-end choice between a security state and Islamist resistance," he said.

Yet Egypt's security apparatus has not just now been revealed, it has been well known for decades. If Mr Cameron believes in exporting liberal values, he could have started by making the UK's political support for Egypt conditional on reform. He can hardly be immunised from criticism by saying he's just come to power; he has been in office since last May.

The truth is, this talk of muscular liberalism is more posturing. He wants to share the views of those in Tahrir Square without lifting a finger to support those risking their lives.

If Mr Cameron really wants to pick a fight over liberal values, he could choose a tougher target. It is one thing to push a tottering Hosni Mubarak - and quite another to enforce the ideals of muscular liberalism on powerful countries like India or China.

On his twin targets of multiculturalism and foreign policy, Mr Cameron's muscular liberalism lacks definition and substance. When Britain's leading tabloid newspaper endorsed David Cameron for the premiership, it did so under the headline: "Cam can have a go cos we think he's hard enough," echoing a challenge to fight often heard on the country's football terraces. If Mr Cameron is looking for a fight, he may have to define more clearly what it is he is fighting for.

falyafai@thenational.ae

'Muscular liberalism' is just Cameron wooing his base

David Cameron's strategy of exporting British values is fatally flawed by a lack of muscle to translate his words into reality.

Most popular today