Sadly, my evening with the Moscow City Ballet at the Emirates Palace had proved an enormous disappointment; the sound system crackled at the high emotion of Tchaikovsky’s Swan Lake and, if the adaptation was baffling, the dancers’ storytelling was woeful. During the interval, the audience couldn’t help being confused.

“Look on the bright side …” someone said to me with a telling pause, unable to complete her sentence. As we still had to endure the second half of the performance, I couldn’t imagine what that bright side could be but, then, I describe myself as a realist rather than an out-and-out optimist. Ask me if my glass is half-empty or half-full and I’ll most likely reply that it’s half-full – I just won’t wax lyrical about it.

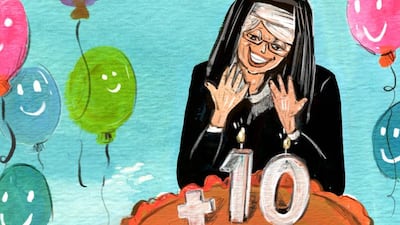

The rosiness – or otherwise – of my world view has registered this week thanks to a debate about The Nun Study.

In 1986, researchers analysed the autobiographical essays of 678 nuns, written in their early 20s, who had entered an American convent in the 1930s to determine whether a positive emotional outlook could affect well-being. Unexpectedly, it found that those in the top 25 per cent on the optimism scale lived on average up to 10 years longer. The implications of this astonishing finding in our increasingly health-conscious age are enormous and growing, even if we’re still not quite sure what to do with the knowledge.

As the writer and broadcaster Dr Michael Mosley told a BBC radio programme this week: “There is almost nothing you can do which will do that [increase your life by 10 years]. If you took up fiendish levels of exercise, you could probably raise your life expectancy by four years, so 10 years is huge.” So why isn’t health policy being redirected towards eradicating pessimism by placing the emphasis on positive minds not fitter bodies?

“Because we are not sure that you can actually change people,” Mosley says. “It’s all very well to say you are an optimist therefore you will live longer, but why are you an optimist? Is it because there is something about your genes? Is there something about your background? If we made a pessimist more happy, or attempted to do so, would that have an effect on them? We don’t know. No one has ever done the studies.”

But that information vacuum did not stop Mosley, a self-described “proud pessimist”, from undergoing a seven-week programme of meditation and cognitive behavioural modification monitored by Professor Elaine Fox at Oxford University to make him more optimistic. Just 20 minutes of meditation per day and five minutes clicking on images of happy faces over sad and he was judged to be noticeably more positive in his outlook. Mosley still meditates because he believes that optimists are happier people. (And his wife, “an annoying optimist”, is happier, too.)

Another factor proven to promote health and happiness is a belief in God and an adherence to religious values, but modern life is seldom a straightforward equation.

Ask Yahya Hassan, the 18-year-old son of Palestinian immigrants now settled in Denmark, who has caused a great deal of controversy with a self-titled book of 150 poems that has sold 32,000 copies in two weeks. In it, Hassan rails against the hypocrisy of his peer group and his authoritarian upbringing, The Wall Street Journal’s blog Speakeasy reports.

His reward for voicing his opinion has been to receive death threats, but his choice – to love literature and to start a debate by picking up his pen – could be described as an act of the most optimistic kind.

cdight@thenational.ae