The telegram arrived out of the blue, heavy with promise but tantalisingly short on detail: "Twelve tumuli of Bahrain type discovered on island off Abu Dhabi can you and PV come – Tim."

The recipient of the message, sent in 1953, was Geoffrey Bibby, a British archaeologist working with a Danish team that was searching for the ancient civilisation of Dilmun in the Arabian Gulf. PV was Peter Vilhelm Glob, one of Denmark's most respected archaeologists, who assembled the team from the Moesgaard Museum in his homeland. Tim Hillyard, the representative of British Petroleum for Abu Dhabi's offshore oil concession, and an acquaintance of both men, sent the telegram.

Shaping the history of the UAE

The team made two discoveries that would transform Abu Dhabi. The first came in March 1958, when the team found the emirate's first oilfield. They made their next discovery about 12 months later, and it raised fundamental questions about the history of that part of the Arabian Peninsula.

Bibby was born in 1917, in north-west England, and studied archaeology at Cambridge. In the Second World War he fought alongside the Danish resistance, and later made his home in Denmark. His account of the Gulf expeditions, Looking for Dilmun, was published in 1961.

Unearthing Dilmun

Bibby and Glob had been digging in Bahrain for several years when they were urged by Hillyard to travel to Abu Dhabi. They believed evidence had been found that the island was once a major part of Dilmun, a civilisation that had dominated trading routes in the Gulf. Dilmun dates back to the late fourth millennium and vanished circa 538BC. Scholars have proposed the civilisation was the inspiration for the Garden of Eden, but it was also a trading empire that connected the routes from the Indus Valley in northern India and Pakistan, to Mesopotamia, or modern-day Iraq.

Dilmun is mentioned in the surviving texts of the Sumerians, one of the first civilisations to develop written language, and is described as a paradise on Earth in their creation stories, including the poem, the Epic of Gilgamesh, the earliest known great work of literature. But the exact location of Dilmun was disputed.

Among the candidates was Bahrain, where the archaeologists had been uncovering the remains of a large city from the same period. The structures they found included numerous tumuli, circular burial mounds built of stone. Abu Dhabi was not considered part of Dilmun at the time and western academics dismissed any prospect of the emirate having anything of value from antiquity.

An audience with Sheikh Shakhbut

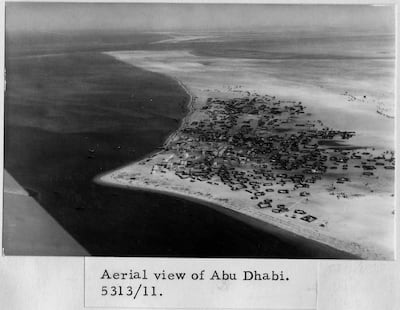

The local people knew otherwise. They had seen evidence of a city on Umm Al Nar, or the "Mother of Fire", an island of sand and flints where old stones could be found. The structure there was built in the pre-Islamic Age of Ignorance. Now uninhabited, Umm Al Nar lies off the coast of Abu Dhabi, beyond the Maqta crossing that separated the island from the mainland. The journey to reach it in the 1950s involved a drive across empty desert, where the city now stands, followed by a short but unpredictable voyage over tidal flats.

In April 1958, Bibby and Glob flew to Abu Dhabi's desert airstrip, where they were met by Hillyard. The men followed protocol and went first to Qasr Al Hosn, for an audience with Sheikh Shakhbut bin Sultan Al Nahyan, the Ruler of Abu Dhabi at the time, whose knowledge of the site may have inspired Hillyard to begin the expedition.

Bibby later wrote that Sheikh Shakhbut was "intensely curious about our work, with an intelligent appreciation of the problems involved in archaeological research in virgin territory and of the light which it could throw on the origins of his people and his country".

Sheikh Shakhbut consumed news voraciously and became aware of the expeditions in Bahrain by reading articles in the Illustrated London News. He was keen to see work begin in Abu Dhabi.

An Abu Dhabi dig

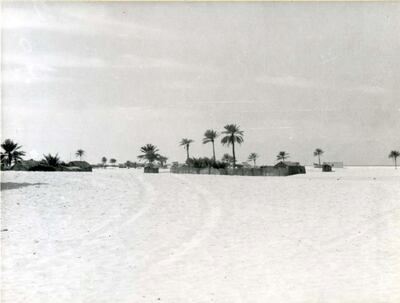

Bibby and Glob visited Umm Al Nar. "It was a good half-hour's drive, first through the deep sand as far as the airstrip, and then out on to the firm sand flats," Bibby recalled. "The actual crossing was scarcely 200 yards broad, though scored deep by the tide race, and we waded ashore on the island and crossed the broad tidal flats to eroded limestone cliffs, where the island in reality began."

Flints covered the island and Glob soon picked out several that had been shaped by human hands, an indication the island was inhabited in the Stone Age. Next, they went to the tumuli, which they believed had been left undisturbed since they were built. But when was that? "On or around the mounds there were no potsherds, which alone could have given us a line," Bibby wrote. "If we could find the means to dig these mounds, we should almost certainly find the evidence which was so conspicuously lacking outside them."

But they had a problem: funding. The site was remote and lacked shelter and fresh water. Accommodation would have to be built, and supplies sourced from Abu Dhabi, which was then little more than a fishing village with a tiny souq. A provisional budget was suggested at £2,000, about Dh220,000 today. The Danish team did not have those funds to spare, and there would be no financial help from the emirate, which was yet to receive any oil revenue. Fortunately, an anonymous benefactor unexpectedly agreed to finance the dig and the expedition was back on.

Preserving history

A four-man team returned to the site in February 1959 and remained there until the April heat set in. The records of the trip are kept at the Moesgaard Museum, where the collaboration with the UAE continues to this day. These include the handwritten names of 15 workers from Abu Dhabi who helped with the dig, and the list of supplies flown in from the oil exploration base on Das Island, including six kilograms of potatoes, a 1.5kg of tinned tongue and two bottles of tomato ketchup. A traditional palm-frond hut was built to provide accommodation. The workforce was driven from Abu Dhabi and was to be paid a daily rate of five Indian Gulf Rupees, the equivalent of Dh40 today.

Work began on two of the mounds, which turned out to be of complex construction. One was not a grave at all, but a building. Fragments of pottery were discovered, similar to those found in Bahrain. It was initially thought the structures were 2,000 years old, but the expedition revealed they could be twice as old as that.

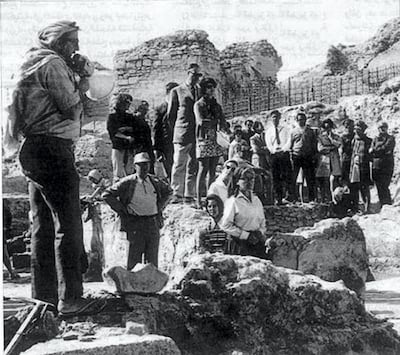

The work also attracted important visitors. "Sheikh Shakhbut showed great curiosity about our work, speculating over what manner of people these could have been, who built their village and their tombs on the island in his territory during the Age of Ignorance," Bibby said.

Also present was Sheikh Zayed, the Founding Father, who was then the Ruler's Representative in the Eastern Region. Sheikh Zayed made an immediate impression on the archaeologists. "His was a name to conjure with – he was a mighty hunter and a renowned desert fighter," Bibby wrote.

Sheikh Zayed also had a surprise for the archaeologists – and an invitation. After surveying Umm Al Nar, he revealed there were possibly hundreds of similar mounds in an area near to what is now Al Ain. Sheikh Zayed suggested the archaeologists go and see them. That visit was in the second week of March 1959, and the team discovered about 200 stone structures that lined lower slopes leading to Jebel Hafeet, near the village of Hili. Both discoveries comprise what is now known as the Umm Al Nar culture, which thrived for perhaps 600 years from around 2,600BC. The Danish teams continued to work on the site until the 1970s, with their work laying the foundation for archaeology in the UAE.

Among the artefacts uncovered were carvings of humans and antelope on what is now called the Hili Tomb, as well as a short bronze sword. A decorated stone cup from Umm Al Nar can still be seen at Louvre Abu Dhabi.

Glob died in 1985, 16 years before Bibby, but four of the surviving archaeologists have since been invited back to the emirate, to meet Sheikh Mohamed bin Zayed, Crown Prince of Abu Dhabi and Deputy Supreme Commander of the Armed Forces.

The work that began 60 years ago helped uncover the history of what would become the UAE. We now know that history stretches back across 120,000 years, and includes the discovery of Ed-Dur, a once lost city that dates back more than 7,000 years was discovered in Umm Al Quwain in the 1970s.

When Bibby first heard of the tumuli of Umm Al Nar, he immediately dismissed the idea that they could be part of Dilmun. But there was another theory: even more mysterious than Dilmun, was the land of Makan, sometimes called Magan. It was from there that the Sumerians obtained their copper, with reports of their ships docking at Dilmun. The most popular theory was that Makan was in Africa, perhaps in Sudan or Ethiopia. Other potential sites include a region of Yemen, and even parts of Pakistan and Iran. But Bibby believed the community at Umm Al Nar could be linked to Makan, with the copper mined from known deposits in Oman, and the mountains that bordered Al Ain and Abu Dhabi.

In the 1970s, archaeological expeditions discovered dozens of copper mines in northern Oman, several of which dated from the Umm Al Nar period. If correct, it would mean that Abu Dhabi's inhabitants from that time were a vital part of the region's trade routes.

The debate has still to be resolved. Another enduring mystery is the reasons why both Dilmun and Makan faded from history. After all, when 4,000 years have passed, what is another 60?