In the late Lebanese artist Saloua Raouda Choucair's "poem" Sculptures, rows of blocks sit atop one another, each nestled into the next. One row's protuberance burrows into a cavity in the block below it, whose middle is itself bulged up by the swelling of the block underneath. Like a visualisation of lines of text, the effect is of difference and unity: a number of diverse ideas coming together as one.

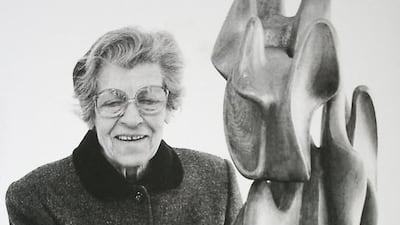

When Choucair died in January, at age of 100, her career had just ridden through a surprise lift, with a well-received retrospective at Tate Modern in 2013, and subsequent participation in a number of international shows and biennials.

As can happen with artists with a noteworthy history, the vicissitudes of interest in Choucair’s work dominated much of the coverage of her death.

She held “the first exhibition of modern abstraction in the Arab world”, with her 1947 show at Beirut’s Arab Cultural Centre, noted a few; others focused on her Tate debut at the age of 97.

Choucair had, indeed, not sold anything for decades when the interest in her work picked up. Her studio was like a large archive, with notes, preparatory sketches, and a full panoply of works stretching back over six decades: paintings, sculptures, models, fragments of poetry, notes on religious texts and correspondence all kept about the room.

It was an extraordinary body of work brought into view – almost at one go.

Choucair was born in Ottoman Empire Beirut and raised by her mother with her two siblings after her father died of typhus in the army. In her 20s she apprenticed with the Lebanese painter Omar Onsi, working in a figurative idiom, but by 1947 she had moved towards abstraction, and she left the following year to study art in Paris.

There she spent time, famously, in the studio of the well-known modern artist Fernand Léger, and one can see the traces of his influence in the flat, almost cartoon-like paintings and gouaches she made during that period: in Les Peintres célèbres II (The Famous Painters II, 1948–49, for example, four seated, nude women face out towards the viewer, holding cups of tea or crossing their arms, all rendered in detail-less projection. The painting notably trades women for men in the title role of Famous Painters.

Throughout the 1950s Choucair’s work became more purely abstract, in paintings of blocks of interlocking colour that echo and respond to one other: a light pink nose-like form talking back to a darker pink one, or a shot of red nuzzled inside a circle of green. Rhythm is a good way to think about these works; like the paintings of Fahrelnissa Zeid, their parts are on the move.

By the end of the 1960s she had mostly stopped making work in oil and gouache and moved on to jewellery, public sculpture (there are two benches by her in Beirut, and another has been recently installed in Doha), and sculpture.

For the latter she worked in a variety of materials – wood, class, brass, fibreglass, aluminium and Plexiglas – even into her 80s, until it became no longer possible for her to create.

Over the years she worked almost within her own language; she called the interlocking sculptures “poems” and later “duals” (her earlier two-dimensional work she had termed “modules”), and made a number of them in the form of maquettes for larger-scale work that was never carried out.

The last of her typologies, made in the 1990s, were double-helix sculptures that she called “sparkles”.

Choucair had remained in Beirut and worked in her studio through the Lebanese civil war.

The times she lived through make her biography fascinating: she helped bring abstraction from Paris to Beirut; she married Islamic mathematics with western influence; she depicts the pain and mournfulness of a city under fire.

And the work itself, so self-contained, withstands these pressures to be read as an index of something else, and searches all the while for new ways to picture the structures of the world.