The Gallic-pop scholar Jean-Emmanuel Deluxe cites 1963 as year zero for the playful, predominately girl-fronted music genre known as yé-yé. On June 22, a concert organised by the nascent magazine/radio show Salut les Copains drew 150,000 excitable baby boomers to Place de la Nation, Paris, trouncing all attendance expectations. Though blousons noirs (Teddy boys) gatecrashed the event and vandalised nearby property, the teenage throng had screamed for acts including emerging yé-yé star Sylvie Vartan. Dubbed “the junior high-school girl of twist”, Vartan would share billing with The Beatles at the Paris Olympia the following year.

In France, home to cherished monoliths of chanson such as Édith Piaf and Charles Trenet, US and UK pop had previously been ridiculed or parodied. Now it was becoming a pervasive force, albeit one that was quickly retooled for French sensibilities. “The media was as stunned as the general public,” writes Deluxe of the Salut les Copains concert. “France was discovering its young people existed and wanted to have their say.”

At the time, Le Figaro journalist Philippe Bouvard was oddly enraged and threatened by events at Place de la Nation. “What is the difference between the twist in [East Paris suburb] Vincennes and Hitler’s speeches at the Reichstag?” he wrote, ignoring the fact that Chubby Checker would have been on Hitler’s hit list rather than his playlist.

All of the above supports Deluxe’s thesis that: “In spite of its light-as-a-bubble appearance, pop music can tell us more than many a sociological essay.” How very French, how very cafe society, though, that the term yé-yé (simply meaning “yeah, yeah”) was actually coined by the sociologist Edgar Morin while writing in Le Monde just after the Salut les Copains bash.

Unlike Bouvard, Morin saw the movement he had named as a positive and admirably passionate one. Deluxe, an evangelistic, long-standing yé-yé fan, is quick to echo the sentiment. “Carefree and candy-coloured, yé-yé music became an oasis of exotic freshness designed to cheer people up,” he writes, but another value-adding trait of the genre was its evanescence. By May 1968, the first wave of yé-yé girls had largely fallen silent. The seeming frivolity of their oeuvre was an ill-fitting soundtrack for the civil unrest and general strikes that were threatening to collapse De Gaulle’s France.

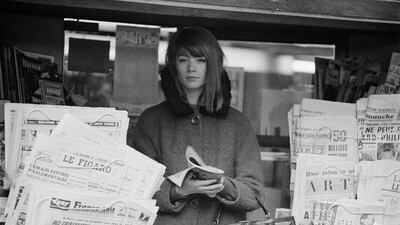

Yé-Yé Girls of ’60s French Pop is extremely easy on the eyes. Part coffee-table book, part painstaking miscellany of all things yé-yé, it doesn’t want for tasteful images of the chic and photogenic young women whose clear complexions were lent extra radiance by the colour-saturation idiosyncrasies of 1960s camera film.

But while it would be disingenuous not to acknowledge the appeal of re-engaging with the doe-eyed beauty of singers such as Danièle “Zouzou” Ciarlet, Deluxe’s volume is not a glorified pin-up book or fashion tome. If you really want to learn about the lives and music of yé-yé’s leading and lesser-known lights, you won’t find a more informative English-language account than this one.

In the cloyingly titled chapter The Four Aces of Hearts, Deluxe singles out France Gall, Françoise Hardy, Vartan and Chantal Goya for special mention. He argues that Gall’s Laisse Tomber les Filles – later recast as Chick Habit for the singer April March in Quentin Tarantino’s 2007 film Death Proof – was a vanguard feminist song, albeit one penned by Serge Gainsbourg, a man, who, for all his artistic brilliance, was often charged with misogyny.

Extraordinarily successful though many yé-yé’s were – Hardy graced the cover of Paris Match under the caption “18-year-old millionaires” – their careers were riven with such paradoxes. The typical fledgling yé-yé was naive but intelligent, artistically potent yet shaped by the male record producers who invariably discovered her. Gall, for one, was resentful in her later years. “He didn’t know me – in fact only projected his fantasies through me,” she said of Gainsbourg.

Deluxe also flags up the power of yé-yé girls as égéries (muses) for fashion designers and rock stars. Bob Dylan namechecked Hardy on the cover of 1964’s Another Side of Bob Dylan and still hadn’t forgotten about her around the time that I interviewed her for The Independent in 2005. “When [Dylan] came to Paris not so long ago he still asked for me – or at least that’s what I read in the newspapers,” she told me. “I am too afraid to go and say hello now. He probably remembers me as I was.”

There’s a slightly eccentric, scattershot approach to Deluxe’s chapter headings in Yé-Yé Girls of ’60s French Pop, but this chimes with the curious tics of the genre under discussion. One minute we’re looking at a collection of yé-yé star lipstick smudges arranged in columns in the kitschy magazine of the period Mademoiselle Age Tendre; the next we’re reading about Gall’s “semi-prophetic” song Teenie Weenie Boppie, an innocent-sounding psychedelic curio that depicts Mick Jagger drowning in the Thames (his bandmate Brian Jones would drown in a swimming pool two years later).

Elsewhere, a chapter titled More Pop Mademoiselles flushes out Clothilde, aka the Paris-born Elizabeth Beauvais, whose two darkly funny 45s followed what Deluxe calls “the dumb and nasty trend of the period”.

Fallait Pas Ecraser la Queue du Chat, which I was pleased to locate on YouTube, finds Beauvais singing about a kitten who gets his tail trodden upon and a perfectly serviceable leg amputated. In Britain, the RSPCA would have been up in arms, and it’s certainly a song that supports Deluxe’s claim that mid-1960s yé-yé lyrics tended to be less hackneyed than contemporaneous ones sung by UK and US chanteuses.

The Parisienne of Polish decent Stella Zelcer is fascinating, too – and partly because she was an anti-yé-yé whose 1963 single Pourquoi Pas Moi (Why Not Me) poked fun at the genre: “My stare is blank/ My brain is soft/ Yes, but the only thing is/ I don’t know any mogul at all.”

The book also has an informative section on British and American singers who recorded in French for the yé-yé market – extraordinarily, Petula Clark released almost 80 EPs in France between 1958 and 1970 – but its oddest (and slightly creepy) chapter is titled Three or Four 45’s I Know About Her.

As Deluxe writes about Carine, a schoolgirl who disappeared in December 1973, leaving behind a treasure trove of yé-yé memorabilia that eventually came into the author’s possession via a car boot sale, I was somehow reminded of Gordon Burn’s disturbing 1991 novel Alma Cogan, which takes its name from Britain’s most successful female singer of the 1950s. Pop’s distant past is not without its darknesses, and yé-yé, with its male-penned double entendres sung by young, sometimes unwitting women, certainly has its share of them. Naturally, Deluxe addresses this.

Despite its era-specific title, Yé-Yé Girls of ’60s French Pop also explores the genre’s influence through the 1970s and up to the present day. I’m indebted to Jean-Emmanuel Deluxe for introducing me to Brigitte Fontaine’s brilliantly arranged 1973 psych-pop album Brigitte Fontaine Est … Folle! (the Anglo-French indie act Stereolab worked with her in 1998) and Veronique Sanson’s icy, early Abba-like 1972 classic Amoureuse, both of which are available on Spotify. Late in the book, Jacques Duvall – “the only songwriter to rival Serge Gainsbourg at his peak”, reckons Deluxe – makes the point that many yé-yé records benefited from the elegant and nuanced playing of seasoned jazzmen, and one can hear that on these and many of the other recordings.

Yé-Yé Girls of ’60s French Pop lifts the lid on a genre synonymous with Gainsbourg and the British yé-yé girl Jane Birkin’s Je T’aime ... Moi Non Plus, taking us on a fascinating journey that YouTube searches can help augment.

“I hope I have transmitted my virus to you, and all together we will shout: vive les filles, and long live la French pop!” concludes Deluxe, á la Eurotrash’s Antoine de Caunes, before his curious volume segues to its extensive discography.

Job done, monsieur.

James McNair writes for Mojo magazine and The Independent.