It's around the midway point in Imaad Wasif's third album, The Voidist, that you begin to worry about his mental well-being. The centrepiece track Return to You is reaching a crescendo of magnificently malevolent rock 'n' roll when the Canadian guitarist's yearning for lost love suddenly becomes a full-blown howl, like a man on the edge of a breakdown. Such raw, on-record emotion rekindles memories of several notable rock casualties, from the frenzy of Jimi Hendrix and the angst of 1990s grunge to the soul-baring of the late Jeff Buckley. And yet his underlying influence is far removed from those tragic figures, and may come as a surprise to casual listeners.

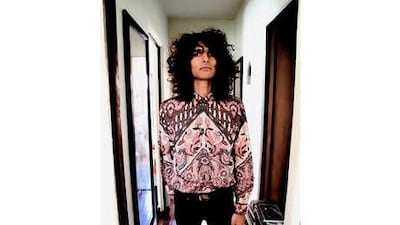

"When I first started playing guitar I was almost trying to emulate a lot of the Indian classical records I had grown up hearing," explains the quietly-spoken musician, who is briefly back at home during a rare break from touring. "I can view it now as a conscious decision that I made at that point, but at the time it wasn't at all. I mean, always in my life there's been a sort of conflict." Tall, wiry, and a striking onstage presence, Wasif is an unsung hero of North American guitar rock. He emerged from the same Palm Desert, California, scene that spawned Josh Homme's mighty band Queens of the Stone Age, became the right-hand-man for influential US rocker Lou Barlow and is now the guitarist the trendy New York trio the Yeah Yeah Yeahs bring in to beef up their sound. His talents are much in demand, then, but each job is really just that: a job. "The thing I seek the most in music is transcendence," he explains, "and the only way I truly ever experience that is by performing my own songs."

Only he truly understands how those songs come about. Wasif was born in Vancouver, to music-literate Indian parents, and still begins each day with a meditative trawl through their extensive vinyl collection. He admits that much of this music is "still a mystery to me", partly because the records' labels were washed away while in the ship's hold during their journey to Canada. The likes of the sitar and sarod maestros Vilayat Kahn and Ali Akbar Khan also loom large in his thoughts, even if his own strings are usually played in a much fiercer fashion. Through the guitar he channels the grand, spiritual majesty of those old recordings.

Wasif only recognised the influence of his musical heritage relatively recently, having actively rejected it in his formative years. Instead he explored a more rebellious path, punk rock, which came as quite a shock to his parents. "They really weren't into it at all," he says. "I can remember my father being like, 'what the hell, why are you listening to this, what's going on with you?' It's only been recently where they've kind of understood what I'm seeking. I took a very circuitous path to where I'm at now. I was exploring far darker music."

His nascent rock career also offered a vital link with like-minded contemporaries, which had previously proven difficult. When Wasif was three years old, his family moved to the Californian desert, for reasons he has yet fully to uncover, but which may well have been artistic. Imaad's father is a Ghazal singer, the ancient Arabic verse dedicated to isolation and unobtainable love, but his son failed to see the appeal back then. "I would hear my father singing and that music made less sense to me than a lot of the American music that I grew up hearing."

The Palm Desert move did eventually see Imaad follow in his father's lyrical footsteps, however, as is particularly evident on the pain-wracked Return to You. "It was a very, very isolating experience culturally," he recalls, "because there was no real Indian community there. It was only very recently that I understood the Ghazal, the Urdu, and the connection: a lot of pining and longing. My own personal exploration of those themes never really came from an idea that was given to me, it was a sort of natural unfolding. But really I believe [love] is one of the great powers that we as human beings share, and one of the things that is, at the same time, completely beautiful and maddening. I'm very interested in the darker edges of all of it as well."

Wasif is a likeable interviewee, but rather intense and often confusingly complex when discussing his craft. This does raise the question of how he copes with the compromise-heavy concept of collaboration. Only one has ever gone astray, he insists, when a role in the recent hymn-based psychedelic rock collective Sabbath Assembly was abandoned because of "a personal conflict with the spiritual content of the songs".

For his new record, he invited members of the US bands Weezer and the Melvins to contribute, as well as his regular rhythm section, Two Part Beast. So how does his studio dynamic work? Is it a dictatorship? "I read a lot about cult leaders," he smiles. "I've just read this amazing book by the drummer for [legendary experimental rocker] Captain Beefheart, his idea that there's some element of mind control in it. It's an interesting idea because I spend a lot of time with these songs, on my own, so when I bring them to other people I have a clear vision of what I want to do with them."

One collaborative effort that did fulfil Wasif's expectations involved the Yeah Yeah Yeahs frontwoman Karen O, on the soundtrack to last year's successful children's movie Where the Wild Things Are, and in particular the haunting theme Hideaway. Wasif was so satisfied with that co-composition that he sounds curiously negative about pursuing potentially less-rewarding soundtrack work, but does then display a welcome flash of wit. He has a famous fan in the Oscar-winning actress Frances McDormand, who is married to Joel Coen, of the brilliant directorial team the Coen Brothers; the Coens, it seems, would be worthy creative partners. "Last Valentine's Day I tried to convince Joel to write a film about cults in Los Angeles and to put me in the starring role of an Indian man obsessed with Roy Orbison," he laughs. "We've since fallen out of touch."

Hence the lonely quest for transcendence continues. Having immersed himself in Indian music, the next logical step is to forge a more direct fusion between those two passions, perhaps on a forthcoming British tour that marks The Voidist's international release, or in India itself. "I think that at some point in my life I'll be able to wholeheartedly pursue that, but it takes such an amount of discipline and closure from other realms of life," he admits. "It's like I've barely penetrated the surface of it, subconsciously."

To sum things up more succinctly, he concludes with a Bob Dylan quote. "Someone had asked him about what the measure of success was, and the idea was something like, 'if the man wakes up in the morning and goes to sleep at night and in the time between does exactly what he wants to do, then it's a success,' and I feel there is a truth to that. But at the same time, that's Bob Dylan speaking." Wasif, on the other hand, must still offer his skills to pay the bills. Like a rolling stone.