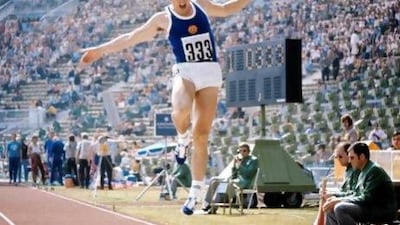

Forty years ago, long before the fall of the Berlin Wall ushered in what certain commentators would call "the end of history" (more on that later), a fan of spaced-out cosmic music in East Germany got an unusual chance to make his communist part of the world a better, or at least fitter, place. His idea, bandied about in the early 1970s with colleagues at a sound studio in Dresden, was to make music to help train athletes for the East German Olympic team. "The music would be hypnotic," he said. "It would bring focus."

So intriguing was his idea that he was whisked away in a mysterious car and interrogated at an athletics camp outside Berlin, where state officials charged with making East German Olympians more imposing on the world stage were eager to hear about any new prospects to increase efficiency and effectiveness in sport. Would metronomic music, with the right rate of rhythm and a capacity to send training athletes into trance states, help in the cause? Maybe, maybe not.

Sounds were imagined and recorded in a studio on tape, with a mind towards the kind of so-called "kosmische" music popular in Germany at the time. It was the era of Kraftwerk, Neu!, Cluster, and countless other cosmic groups who conjoined the otherworldly wildness of electronic sounds with a Teutonic sense of rigour and order. Machines figured prominently in the mix, and what is an athlete if not a ritualistic and regimented sort of machine?

It's hard to know how much the music made for training factored into Olympic success at the time, but its remnants can be heard on a new collection called Kosmischer Läufer Volume 1: The Secret Cosmic Music of the East German Olympic Program 1972-83. The first part of the title translates as "cosmic runner", and, indeed, the sounds assembled were strategically conceived for a "relaxed 5 kilometre run", with a brief opening passage for warm-up, an extended middle fit for a healthy jog, and a short tail at the end paced to wind it all down.

The ambient opening track, Zeit Zum Laufen (Time to Run), introduces a sense of celestial weightlessness before Sandtrommel (Sand Drum) brings in a metronomic beat. And what a beat - shaking from side to side while pushing forcefully forward, it sounds somehow sympathetic to the hesitance that besets the beginning of a run - the sense that a lot of energy is about to be expended. And to what end?

It's here that the exhilarating "motorik" sound of Germany at the time takes hold, with drums that fall into perfect sync with all the funky components of other stuff put to work overhead. Guitar played in galloping fashion, bass that is insistent on keeping its concentration, lots and lots of synthesiser - such are the elements employed on Kosmischer Läufer to make people run.

The fourth track, Tonband Laufspur (Tape Running Track), interestingly introduces a breakbeat that eases up the mind-erasing glide of everything that came before. It still moves at a swift pace, but the unsteadiness of it makes you think. Then comes a burst of guitar that drops into a chugging drone, much like the sound of stated English kosmiche aficionados, Stereolab. The guitar is crisp and clear, round and expansive and many-splendoured in the way it was recorded. It brings the energy level up again.

But wait - wasn't this recorded in 1972? How come other records from the period sound so distant and dry by comparison? And wait, now that we're taking pause to think - is it really possible that a story so grand could have gone unknown and unchronicled for more than 40 years?

The answer, for better or worse, is probably not. Prior to the Kosmischer Läufer release, it seems, mentions of the ostensible creator, Martin "Z" Zeichnete, in the omnipotent archive of everything online, amount to precisely zero. There's no mention of the programme or anything else like it, either. In answer to an email sending early word of praise and asking whether the Kosmischer Läufer music is really of the vintage that it claims, Drew McFadyen, of the label Unknown Capability Recordings, wrote: "Glad you're enjoying the music. You are free to think this release is real, fake, art, or nonsense, but it certainly isn't a hoax."

We've been down this road before, and recently. In just the past two years, the realm of electronic music has greeted the invented memories of Jürgen Müller, an alleged marine biologist-turned-hobbyist ambient-music composer, and Ursula Bogner, a departed German woman said to have made a private stash of great electronic recordings for herself in the 1960s. Neither proved to be verifiably real, but the sounds credited to them garnered much in the way of attention.

So what does it say about the state of music that reimagining the past would seem to be more appealing these days than projecting into the future? Wasn't electronic music meant to be in the progressive wing of things, the soundtrack with which to aid and amplify the thrilling (if also sometimes unnerving) sense of future-shock all around us?

When the Berlin Wall came down in 1989, the political commentator Francis Fukuyama proposed a new notion of "the end of history". It had nothing to do with the state of contemporary music, of course, but it did suppose to be able to identify "the end point of mankind's ideological evolution". (In political terms, that would be "the universalisation of western liberal democracy as the final form of human government".)

Such an idea is easy to disregard as overly sweeping or hubristic in its sense of scale, but what if, in the simplest terms, some sort of "end of history" in music is nigh? With the future contracting out in front and the past so fully mined that fictional history now has to stand in for the real thing, is a sense of fated stasis upon us? Does envisioning such a state represent newfound freedom from hyperawareness of the past, or is it more a failure of imagination?

Many questions spring to mind, but one answer relating to Kosmischer Läufer is the same either way: it remains a great soundtrack with which to run. In that, it actually does slot in with real historical artefacts. One, just six years old, is 45:33 by LCD Soundsystem, which crafted a masterful extended-track electronic disco suite that plays around with the notion of messing with a runner's head. ("Shame on you," it coyly whispers near the start, just when the jogger's sense of accomplishment begins to balloon.) Questions relating to its genuine investment in running were answered by its having been commissioned, presumably to sell shoes, by Nike.

Before that, from a slightly different vantage, came Kraftwerk's famous fixation on bicycling. It was put to song in the early 1980s in Tour de France, complete with heavy breathing by a biker seeming to exert himself as the song rolls along, and group member Ralf Hutter has been said to have, earlier in his career, cycled up to 200km a day. "Cycling," he told an interviewer in 2009, "is like music. It is always forward."

Was he correct? Is music, then, like cycling? Does it always move forward - progress, mutate, transform - or does it sometimes pull up and spin its wheels?

Andy Battaglia is a New York-based writer whose work appears in The Wall Street Journal, The Wire, Spin and more.

thereview@thenational.ae