The adage that “small is beautiful” is one that streaming music service Spotify will be banking on.

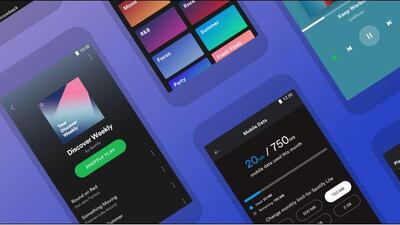

Last week, the firm launched Spotify Lite, a slimmed-down version of its mobile phone app, across 36 territories including the UAE. Its purpose: to enable the service to work smoothly on older devices that have less power, less storage space or poor connectivity. Spotify Lite is one 10th of the size of its sibling, it streams music by default at "Basic" quality – just 0.5MB per song – and claims to make savings on data consumption, battery life and storage space. It has become the latest of a class of apps which have dispensed with premium features and stuck to core functionality, and they've become highly popular. But that popularity has posed the question of whether the standard versions of apps are bloated with features that most people simply don't need.

It's easy to imagine software companies believing that we all have the latest computers, tablets and phones, and being desperate to utilise that processing power to bring us wow-factor features. But across large parts of the world, people are using perfectly good devices that just happen to be a lot older. When Uber was developing its Lite app for launch in India, Brazil and Mexico, its researchers found that the majority of people used Android phones that were at least five years old. They also found that 35 per cent of users were in areas that suffered from poor mobile data connectivity. While Silicon Valley obsesses over $1,000 (Dh3,672) handsets, the advent of 5G and the capabilities of both, it's clear that the circumstances of many potential customers are being forgotten.

This isn’t a new phenomenon. Even in the late 1980s, it was noted that software had a tendency to outgrow the capabilities of the hardware tasked with running it, and in 1995 Swiss scientist Niklaus Wirth wrote a notorious article entitled “A Plea For Lean Software”. This gave rise to what’s known as Wirth’s Law: software gets slower more rapidly than hardware gets faster. The supposed upside of bloated software is additional functionality and features, but Wirth reckoned that this complexity didn’t equal sophistication. “These details are cute, but not essential,” he wrote, “and they have a hidden cost.”

The blame can’t be laid entirely at the door of software developers. Consumers constantly express their desire for more new features, not fewer, and software that fails to progress is likely to be demolished by its competitors.

But that need for rapid evolution, coupled with an often extravagant approach to writing code, results in one thing: big apps. A study done in 2017 by market research firm Sensor Tower showed the extent to which they're growing: Snapchat's size ballooned from 4MB to 203MB in a four-year period, while Facebook, then weighing in at 388MB, was only 32MB back in 2013.

One developer, Ben Sandovsky, neatly summed up the problem in an interview with the website Gadgets 360: "Employees at these companies live in an early-adopter bubble," he explained. "They have fast Wi-Fi at home, and phones with 64GB of storage. This creates a huge blind spot around your average user."

Those average users, and indeed those who use devices even older than average, number in the hundreds of millions. Little wonder, then, that firms in search of subscriber numbers now have those people in their sights, and are hurriedly developing software that will be usable in parts of the world where handsets are slow and cheap, and data is slow and expensive. The roll call is growing by the month. Tinder announced this week that it's launching a "Lite" version of its dating app in Vietnam before rolling out across South-East Asia. It joins others such as YouTube Go, which launched in 2016 and now brings its low-data video service to more than 100 countries; Facebook Lite, weighing in at under 1MB and featuring just its "core experiences"; Instagram Lite, which dispenses with messaging and video sharing in its quest to slim down; and various apps made by Google, including Google News Lite, Google Go, Gmail Go and Chrome Lite.

The reaction to these apps when they appear is almost uniformly positive. It's as if a service has had a makeover; it's been stripped of its unnecessary features and the excessive demands it places on our devices, and reminds us of what initially attracted us to it. But Lite apps aren't immune to the "feature creep" that has bloated its bigger brothers; back in December, Facebook introduced animated gifs to its Messenger Lite app, prompting many to wonder which part of "data-saving" Facebook doesn't understand? But the austere, Lite experience doesn't satisfy us for long.

The prospect of extra features, like a siren on the rocks, will always lure us in. Apps are big, to paraphrase developer Jamie Zawinski, “because your needs are big. And your needs are big because the internet is big.”