A white stallion erupts from beneath the red desert sand. The setting is Pakistan in 1977, on the brink of a fateful military coup.

The film is The Blood of Hussain (1980), a gripping political thriller about insurgency in the Sufi heartlands of Pakistani Punjab, reminiscent of Gillo Pontecorvo's The Battle of Algiers. Surreal, yet rich in political metaphor, its memorable opening exemplifies the sublime cinematic vision of director Jamil Dehlavi, which comes to London's British Film Institute this weekend for screenings, co-curated by film scholar Timothy Cooper and myself.

The first of its kind to acknowledge a Pakistani filmmaker, the retrospective titled Between the Sacred and the Profane: The Cinema of Jamil Dehlavi presents a rare opportunity to examine the contribution of one of the most intriguing and least understood figures of cinema. Dehlavi's award-winning corpus encompasses experimental shorts and features dating back to the 1970s, as well as more accessible, televisual dramas produced in the latter stages of a still-unfolding career that spans almost half a century.

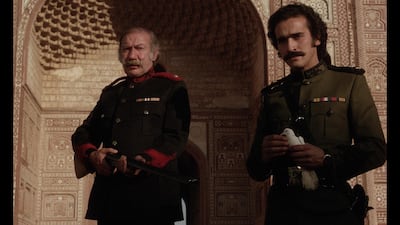

In Pakistan, he is best known for Jinnah, his portrait of Muhammad Ali Jinnah, founder of the nation, in an acclaimed 1998 biopic starring Christopher Lee, also known as the Dracula of 1958. But The Blood of Hussain, rarely screened since its brief release in the early '80s, is a prophetic tour de force.

Punished for his clairvoyance after Gen Zia-ul-Haq's military coup of 1977, Dehlavi was driven into exile in London, where he completed a series of modestly budgeted yet aesthetically adventurous productions exploring religion, myth and spirituality. Born of Fire (1987), an art-house horror about a flautist who ventures to Anatolian Cappadocia to uncover the secrets of his father's mysterious death, was funded by Channel 4. Imbued in the Islamic cosmology of djinns, its cryptic plot unfolds amid hallucinatory visions of whirling dervishes and fiery demons in an atmospheric landscape of cone-shaped Bronze Age rock formations, haunted by the ghosts of the cave-dwelling Christians who sought refuge within them in the Byzantine era. In the opening sequence, a levitating skull eclipses the sun.

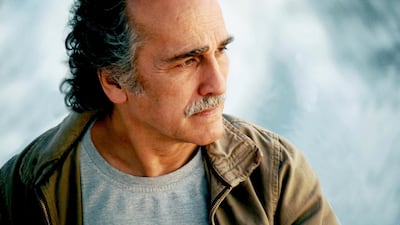

Decoding such works is no easy task. A newspaper profile once ran the headline “Salvador Dehlavi”. The filmmaker himself, an enigmatic figure, is notoriously reticent about discussing their significance, having opted for a largely private life between Karachi and his north London home, a magnificent converted chapel, where I quiz him about his influences.

"They're a combination of so many things," he says cautiously, as I speculate about their relation to European and Iranian modernism. "I don't think in those terms," he replies when I offer labels such as "surrealism". Politely, he declines political or didactic intentions behind even his most incendiary works, emphasising his identity as a visual storyteller who follows his intuition.

Debonair, despite being casually dressed and unpretentious, Dehlavi has a biography that bespeaks high-societal origins. Born in Kolkata in 1944 to a French mother and a father who was a diplomat subsequently posted to Rome and Paris, he was educated at Rugby School and Oxford University, before being called to the Bar at Lincoln's Inn. Opting to pursue film after years of practising fine art, he muscled his way into Columbia film school, despite them initially rejecting his application. The head of department subsequently overturned this verdict after Dehlavi flew to New York to make his case. The imprint of his cosmopolitan formation pervades the breathtaking imagery of Towers of Silence (1975), a Gothic, dreamlike montage of ancient burial rituals shot in Karachi and New York, inspired by an uncle who had eloped with the daughter of a Zoroastrian high priest. Rich in western and Indo-Persian mysticism and mythology, the film's most memorable sequence portrays an exquisite Zoroastrian priestess commanding a flock of vultures to devour a carcass, evoking a cosmos in which the feminine reigns supreme.

Never one to shy away from stripping down for the camera, the director himself appears in several early works as a brooding on-screen presence, his younger bohemian self the embodiment of a dark, sensuousness. Many later films brim with a carnality, combined with Dehalvi's continued interest in religion: Immaculate Conception (1992), a psychological drama about a couple seeking fertility from a Sufi cult, and Passover (1995), an abstract musical collaboration with Dehlavi's flamenco guitar teacher Paco Pena. The latter, a BBC commission, restages the Passion of Christ in Andalucia, the European heart of medieval Islam.

Despite supernatural and sacred themes, many of these works feature plotlines and characters whose journeys – like Dehlavi's peripatetic life – are entangled with the modern condition in cosmopolitan cities; many focus on the fraught, at times sordid encounter between East and West. With subject matter ranging from Partition to the War on Terror in Infinite Justice, a 2007 thriller loosely based on the Daniel Pearl murder, the result is a compelling alchemy of religion and politics, in which race, desire and the thorny relationship between imperial powers and their former colonies is examined with unnerving honesty.

Actors who have worked with Dehlavi pay testament to his quiet manner and capacity to draw out their finest performances. The late Christopher Lee described his role as Jinnah as his best work. Nabil Shaban's memorable portrait of Peter Firth's mute half-brother in Born of Fire was, he insists, among his most important in an illustrious career. English actress Kika Markham, who plays Katherine, wife of one of the brothers at the heart of a fratricidal saga that runs through The Blood of Hussain, recalls her time on set with fondness and pride. The film's revolutionary sympathies chime with her own as a lifelong anti-war campaigner, and a champion of independent cinema who starred in Francois Truffaut's Two English Girls (1971).

Dehlavi is not without critics, among them Pakistan's former High Commissioner to London, academic Akbar Ahmed, with whom he clashed in an ugly dispute over ownership of Jinnah. Despite emerging intact from several such battles, war-weariness creeps into his tone as he recalls them.

The mantle borne by independent filmmakers in Pakistan, a country in which movie theatres are periodically torched by religious fanatics and where critical thought is rarely rewarded, weighs heavily. Without Dehlavi's tenacity, films such as The Blood of Hussain – smuggled out of Pakistan to London for editing before the director's own surreptitious overland journey via Afghanistan – might never have been completed. As for making a biopic about Jinnah, a revered figure whose portrait adorns every banknote and office in Pakistan, few filmmakers would have embarked on such a potentially explosive project in the first place. Fewer still would have driven it through to completion once its release became mired in a dispute.

Dehlavi’s intimate, sympathetic portrait of Quaid-i-Azam [The Great Leader], an otherwise austere and distant figure, suggests affection for his homeland. So too the fact he returned to teach filmmaking in Karachi. “As children, we were patriotic,” he says, confessing to having imbibed the nationalism of his father’s generation, which “created the country”.

At the same time, he recalls their colonial sensibility with ambivalence, identifying, like many of his contemporaries, with marginalised peoples and outsiders. Passover places "gypsy" protagonists at the heart of the crucifixion; Infinite Justice emphasises the three-dimensionality of Muslims who turn to extremism. Throughout our interview, Dehalvi remains elusive, with his answers brief and precise. Yet his films belie this reserved exterior. QAF (1984), featuring footage of a real volcanic eruption in the Reunion Island, is less a film than a kinetic painting. In capturing the mesmerising force of nature, it represents divine power, taking its name from a sacred mountain at the centre of Islamic cosmology. Dehalvi filmed it himself from a helicopter that almost spun out of control as he ordered the pilot to get dangerously close, risking both their lives. "Adrenalin overtakes," he admits coyly, in a rare admission of emotion. "One loses one's fear when behind a camera." Watching the lava spit awesomely, like an apocalyptic judgment, one can't help but feel the film succeeds, like few others, in representing the unseen.

___________________

Read more:

‘Harb Karmouz’ fails as a historical drama due to poorly written characters

Haifaa Al Mansour is returning to film in Saudi Arabia

Manav Bhalla on his Dubai movie and Om Puri's final performance