Rian Johnson has joked that he may be the subject of his own murder-mystery storyline after he gave away a crucial trade secret during an interview with Vanity Fair.

The director of Star Wars: The Last Jedi and Looper was dissecting an early scene from his latest big-screen outing, the old-school whodunnit Knives Out, for the US magazine's YouTube channel when he revealed: "Apple; they let you use iPhones in movies, but, and this is pivotal if you're ever watching a mystery movie, bad guys cannot have iPhones on camera" – a bombshell he said, also on camera, would probably leave him in trouble (to put it politely) with the next mystery movie he writes.

Product placement is nothing new in film. It dates back to, at the very latest, Buster Keaton and Fatty Arbuckle's 1920 comedy The Garage, which featured sponsor Red Crown Gasoline's logo prominently in several scenes.

The iPhone question seems a little more interesting, however, as Johnson rightly notes. Not only has he given away a secret of Magic Circle proportions, leading him to surmise that "every single filmmaker who has a bad guy in their movie that's supposed to be a secret wants to kill me right now," but he's also revealed an impressive level of subconscious on-screen manipulation that, while long suspected, may never have been articulated quite so loudly.

The "no iPhones for baddies" rule seems to take us to a level beyond product placement. It is, after all, technically product non-placement, which seems to lead us down a whole new road in terms of the lengths to which companies will go to project their brands positively in movies. Or, in this case, not project their brands negatively.

Product placement, or as 21st century marketers prefer to term it, "brand integration", is everywhere. When it's done well, or at least unobtrusively, it can be fine. Who hasn't wanted to drive an Aston Martin after seeing James Bond see off the latest threat to world peace? Who didn't want a Nokia flip phone after watching Neo bring down the reign of humanity's computerised oppressors in The Matrix?

These films manage to be simultaneously aspirational in terms of the shiny objects being displayed before us, and non-didactic in to-camera monologues about the hand-stitched leather seats, and that's kind of innocuous enough.

Bond would drive a car whatever it happened to be, and Neo would need a phone to connect to his dial-up modem. They might as well be an Aston Martin and a Nokia, especially if the brands are prepared to hand out a significant proportion of the film's production budget before a single ticket is sold. In the 2012 Bond film Skyfall, for example, the Dutch brewer Heineken paid $45 million (Dh165.2m) up front – almost a quarter of the film's budget – to place its offering in the super-spy's hands.

That's before we move on to sponsorship deals with Aston Martin, Omega watches and many, many more, especially as the huge franchise's producers have enough clout to keep the advertisers well away from editorial control.

Then, of course, there are the less subtle attempts at audience manipulation – the ones that surrender all pretence of editorial control for the sake of a few dollars, and I’m looking at you, Will Smith.

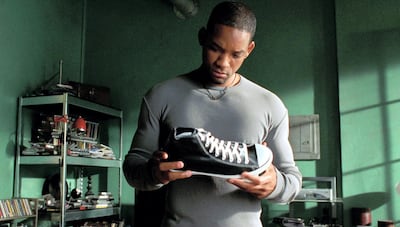

The 2004 sci-fi film I, Robot, in which Smith starred, featured some of the most cringeworthy, unnatural dialogue to make it to the screen. A genuine example of its shocking lines runs thus: "What is that on your feet?"

"Converse All Stars, vintage 2004. Don't turn your face up like that. I know you want some." A later scene features the utterly unnecessary line "nice shoes". That is when product placement has definitely gone too far.

But the phenomenon is by no means entirely negative.

We've already seen how even big-budget blockbusters can benefit from it financially, while seemingly keeping control of their own script, and indie budget films perhaps benefit even more. I could write pages on the number of UAE filmmakers who have told me they could never have made their film without the help of a car dealership that lent them its vehicles, or the hotel that allowed shooting on its grounds or accommodated cast and crew, in return for a prominent shot of its branding. That's not so bad.

The relationship is also a two-way one – for every can of Dr Pepper that appears in your film, the movie is advertised on a Dr Pepper can, and this works for the smaller guys, too. In a delightfully meta piece of filmmaking, Morgan Spurlock found himself directing the in-flight safety video for JetBlue Airways as part of the deal struck for his 2011 documentary The Greatest Movie Ever Sold, ironically a film about the documentarian trying – and succeeding – to make a film funded entirely by product placement. That kind of advertising is gold dust to an independent documentary maker, but it can't hurt the latest Marvel or DC epic, either, when the film is leaping out at you from every fast food carton on the planet at lunchtime.

As for the Apple versus bad guys scenario, I must admit, I'm left a little bit flummoxed, and for one simple reason. When Apple launched the iPhone in 2007, it was a truly groundbreaking product, both in terms of technology and design. Since then, every other tech company on the planet has followed the template to the letter, to the extent that people can't even tell the difference.

If Apple really wants to subtly set itself apart from the bad guys in movies, maybe it should have them simply sitting with a fully charged phone and a straightforward USB lead, while the rest of the cast hunt not for a murderer, but for those white Thunderbolt charging cables that are nowhere to be found when you're outside of your own Apple-dedicated flat.