London-born author Jamal Mahjoub, in his new memoir A Line in the River: Khartoum, City of Memory, remembers the libraries of his life. There was the British Council library, set in a grand villa on a manicured university campus, and there were other libraries he saw during years of wandering, but one particular place stood out: the book and manuscript-piled room of his father's old friend (and his own namesake) Jamal Mohammed Ahmed, a grave and quiet scholar bent over a desk writing in longhand.

Even years later in Denmark, Mahjoub writes, the one library he most recalled was that room of Jamal’s: “The garden was now a pine forest and the writer behind the desk was me.”

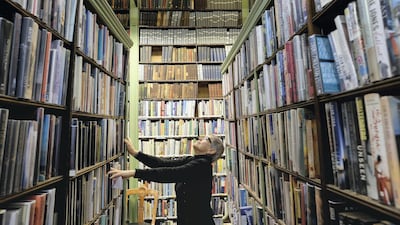

That easy slippage of years, that gentle transformation from a young reader to an old reader – these are among the many pleasant mysteries fostered by libraries and described so feelingly by Stuart Kells in his new book The Library: A Catalogue of Wonders. "Shelves of books are an apt metaphor for communication across time," he writes, "linking past and future, and an apt signifier of infinity and immortality."

Great libraries, wrote the novelist Penelope Lively, tend to be "anything and everything," and The Library: A Catalogue of Wonders charts that quality of mutability through the long history of an idea, from cuneiform tablets in ancient Mesopotamia (available to patrons on trays, although presumably not for withdrawal) to the legendary great library of Alexandria (always a star player in any book about the history of libraries) to the locked and chained cloister libraries of the Middle Ages, and the explosion of literacy at the dawn of the modern era.

Kells points out that the widespread availability of writing materials increases the number and vitality of libraries; Baghdad in the eighth century, for instance, was an important centre for the production of paper and thus became a focus for intense literary concentration. And when the printing press came to England in 1476 with the works of William Caxton, the country’s many monastery libraries began to fill with countless treasures of the written word.

And this was of course a fragile victory; as Kells goes on to mention, this rosy picture darkened only a generation later, when in the 1530s, England’s monastery libraries were largely destroyed, their torn-out manuscript pages being used to “wrap food, scour candlesticks, or polish boots”.

The Library occasionally strays from its enormous main subject to tell amusing stories tangentially connected to libraries. Kells writes about the rare-book trade, about celebrated "book-people" and his halting, often funny attempts to join their ranks.

He relates anecdotes about the peculiar monomania of bibliophiles, as in the case of the philologist Budaeus, who was contentedly reading in his study when a servant rushed in to tell him the house was on fire. “Tell my wife I never interfere in the household,” he said – and went right on reading. Kells likewise tells stories about some of the world’s most famous libraries, places such as the Bodleian or the Folger – or the Vatican Library, which has been the subject of so many outlandish theories in the bookish world.

“More than one bibliophile has fantasised about infiltrating the secluded holdings, which are pictured as an inaccessible wonder, stretching back to Ancient Rome and the birth of the Church, and containing all the best books and all the worst ones,” Kells writes, quickly adding: “In several important respects, that picture is a false one.”

There are also discussions of the funding of libraries, the public perception of libraries, and even the physical set-up of libraries. As Kells points out, libraries require light, but in the days before electricity, lamps and candles presented omnipresent dangers to the shelves and shelves of dry paper all around them.

______________________

Read more:

Book review: Chronicling the life of the brilliant but often baffling Jeff Buckley

Book review: Avedis Hadjian’s Secret Nation tells plight of Turkey’s Armenians

Book review: The Baghdad Clock is a compelling tale of two girls' journey to adulthood

______________________

The solution of course was to construct libraries to allow a maximum amount of natural light – a principle of architecture that was pursued in a grand scale by the Ancient Greeks and Romans (the massive two-wing library built in Rome by the Emperor Trajan was flooded with light), and that’s still embraced even today.

But the book's main theme is the one hinted in its subtitle: a thread of wonder runs throughout these pages, weaving in and out of the subject of libraries in general – the strangeness of the idea, the intrinsic appeal of the idea. Alberto Manguel, in his new book Packing My Library, takes a slightly pessimistic tone, referring to public libraries as "an essential instrument to counter loneliness", but the tone of Kells' book is far more celebratory, a testament to all the ways libraries shape their patrons.

“Libraries are much more than mere accumulations of books,” Kells writes. “Every library has an atmosphere, even a spirit. Every visit to a library is an encounter with the ethereal phenomena of coherence, beauty, and taste.”

Patrons of that native spirit can be near-religious in their advocacy. Petrarch instructed his house servants to guard his home library as they would a holy shrine, and all library fans will report similar stories of the near-religious awe they felt upon first experiencing their local branch.

"We go to libraries perhaps because we love telling ourselves stories and are drawn to the places where these stories are held," wrote Alice Crawford in her 2015 book The Meaning of the Library. "What we find in libraries helps us to shape things and make life seem coherent."

The Library: A Catalogue of Wonders closes its story with an eye to the future of the institution: the complication of digital holdings, the broadening nature of the library's evolving role as far more than a repository of books – but as vibrant community centres whose treasures are free to all who enter.