A Thousand Hills: Rwanda's Rebirth and the Man Who Dreamed It Stephen Kinzer John Wiley & Sons Dh100 In November 1959, Paul Kagame narrowly escaped being hacked to death by anti-Tutsi mobs. His family fled Rwanda, crossed the border into Uganda, and began a life in exile. Three decades later, Kagame returned to his homeland as the head of an invading army, the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF). His return in mid-October 1990 - after departing early from a visiting officers' course at Fort Leavenworth and evading capture in the United Kingdom, Ethiopia, and Kenya - marked the beginning of a long and bloody struggle to topple the Hutu-led government that had chased his family away 30 years earlier. In A Thousand Hills: Rwanda's Rebirth and the Man Who Dreamed It, the veteran New York Times correspondent Stephen Kinzer recreates the battles between the RPF and the Rwandan government forces in vivid detail.

His early chapters are a damning indictment of the international community's inaction in the face of genocide. Kinzer does not hide his contempt for the former UN Secretary General Kofi Annan, who was at the time in charge of peacekeeping operations. According to General Romeo Dallaire, the Canadian who led the emasculated UN peacekeeping forces in Rwanda, Annan repeatedly shut down his efforts to take a more aggressive stance, even in the face of Dallaire's warnings of impending genocide.

Kinzer reserves his most scathing criticism, however, for the French government. He recounts the close friendship that developed between the sons of the French prime minister, François Mitterrand, and the Rwandan president, Juvenal Habyarimana, and France's obsession with maintaining its sphere of influence in Francophone Africa, a goal that was threatened by a Ugandan-trained, English-speaking rebel leader like Paul Kagame.

Driven by this modern-day Fashoda syndrome, Paris armed the Hutu-led regime prior to the genocide, sent troops and materiel to fight the RPF, and eventually created a safe zone in southwestern Rwanda to which fleeing Hutu génocidaires flocked after committing their crimes. Kinzer's narrative makes clear that Rwanda's subsequent invasions of Zaire - now the Democratic Republic of Congo - to stamp out infiltration by Hutu militants would probably never have occurred if the armed Hutu refugees, many of whom had participated in the genocide, had been disarmed before entering UN-administered refugee camps.

As the The Guardian's Chris McGreal recalled in 2007, after Kagame expelled the French ambassador and shuttered numerous French cultural institutions, "The French soldiers did rescue some Rwandans. They took the assassinated president's wife (a notorious anti-Tutsi extremist in her own right), and various Hutu politicians who helped organise the genocide". He adds, "They also remembered the French embassy dog, which was carefully loaded on to an army lorry while a Tutsi man who ran up to beg for help was turned away."

Kinzer's writing is strongest when conveying his moral outrage at western governments' indifference and complicity in the genocide. In a chapter on Rwanda's newly thriving tourist trade and the visitors who pay $400 (Dh 1,468) to go hiking in the Virunga Mountains to see endangered mountain gorillas, he quotes General Dallaire, who wondered "if the international community would have done more if eight hundred thousand mountain gorillas were being murdered".

Before 1994, few people had ever heard of Rwanda. Since then, the country's name - like the Polish town of Auschwitz - has become synonymous with genocide. Countless journalists and academics have written about the devastating massacres that left nearly one million people dead in the spring of 1994, most notably Philip Gourevitch in his acclaimed book We Wish to Inform You That Tomorrow We Will Be Killed with Our Families. But few writers have considered what has risen from the ashes.

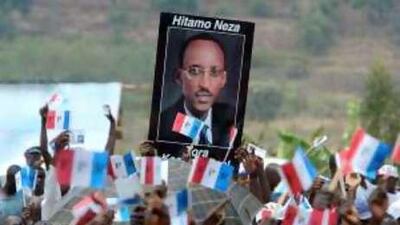

Just 14 years after the genocide, Rwanda's government has built a thriving economy, lured investors from across the globe, made great strides against government corruption, and boldly declared that it wishes to emulate the development and growth achieved by "Asian Tigers" such as Malaysia and Singapore and set an example for the rest of Africa. A Thousand Hills chronicles the political history of Rwanda before and after the genocide. It is also a biography of sorts. Kagame is the central character and frequent narrator, and his italicised commentary is spread liberally throughout Kinzer's book. Embattled and misunderstood leaders are Kinzer's stock-in-trade, and Kagame fits the mould of the real-life protagonists featured in Kinzer's earlier works, namely Iran's Mohammad Mossadegh and Guatemala's Jacobo Arbenz. Both leaders were deposed in US-led coups during the 1950s and received sympathetic - though not uncritical - attention in Kinzer's previous books: All the Shah's Men and Bitter Fruit. But Kagame is different. Far from being a historical personality reconstructed from the archives, the Rwandan president was a willing participant in A Thousand Hills. He sat for more than 30 hours of interviews and clearly made a tremendous impression on Kinzer, as he has on hundreds of other western admirers.

Kagame also has prominent detractors. The best-known is Paul Rusesabagina, who became famous as a modern-day Schindler in the Hollywood movie Hotel Rwanda. Rusesabagina accuses Kagame of suppressing any form of dissent or political opposition and purposely stifling the development of a new generation of Hutu leaders. Similarly, Alison Des Forges of Human Rights Watch insists that many resentful Hutus feel there is no possibility of justice for them in the new Rwanda. "Development is at the top of their list," she says, lamenting Kagame's priorities, "and justice is seen as a nuisance".

As a result of Kagame's extensive involvement and Kinzer's deep admiration for him, the book occasionally reads like a hagiography rather than a biography or narrative history. Kinzer is by no means uncritical. He notes, for example, that Kagame could seriously investigate reports of human rights violations rather than ignore them and dismiss his critics as people who had "probably consumed drugs".

But in the end, Kinzer plants himself firmly on Kagame's side. "Just across the border in the Congo…lie forces eager to destroy what Kagame's government is building," he argues. "In this climate, permitting European-style democracy would be folly. It might well lead to another genocide." In a country still recovering from the systematic murder of more than 10 per cent of its population, Kinzer believes that the benefits of a temporary benevolent dictatorship greatly outweigh the risks of absolute democracy. Kagame and his followers seek to translate development theory into practice. "History suggests they will fail," writes Kinzer. But, he argues, "if they succeed, they can change the world."

Sasha Polakow-Suransky is an editor at Foreign Affairs in New York.