An aircraft serves as the setting for the majority of my new novel, Turbulence.

The protagonist, Dunya, watches her husband at the airport check-in counter. She sharply observes the attendants behind the desk and notes their ruby-hued lips, while reminiscing about a short film she once made about how red lipstick symbolises hyper-feminine allure.

This oscillation between past and present is characteristic of Dunya, who observes situations in real time and then reflects on how she would have responded or reacted a decade ago, when, pre-marriage, her values and priorities were completely different from the lifestyle she inhabits as a wife and mother in the Middle East.

The country Dunya is flying away from is not relevant. It’s her journey, rather, that proves to be pivotal to the process of learning, unlearning and discovering herself throughout the course of the story. Upgraded to business class, away from her husband and son, Dunya’s 14-hour flight becomes a portal to a dramatic transformation on a metaphysical level. She recounts memories, regrets choices she once made and then unlocks a shocking discovery that triggers her early labour, in the air.

This climactic moment was inspired by a real event. In 2020, a Nigerian woman gave birth on an Emirates flight to Lagos, and when I became pregnant almost a year later, that story came back to me. For passport and citizenship purposes I was flying to Canada to give birth, and the prospect of going into labour mid-air was terrifying.

My non-fiction book, Modesty: A Fashion Paradox, had been published the year prior, and I had been toying with the idea of writing fiction. It was this news story from the pandemic that served as the creative catalyst for the novel. The protagonist, supporting characters and storyline were all made up – I wanted to test the extent of my imagination while crafting characters who were, most importantly, relatable. I also wanted to integrate an element of social commentary. In many ways, Dunya provides an outsider’s lens on the lives of the well-heeled in the Gulf.

As a young and idealistic university student in New York, Dunya had grand plans about becoming a game-changing filmmaker who would shed light on important causes and help rectify misconceptions about her community. But when she falls in love, she starts making sacrifices, and as those compromises grow greater, her own dreams start getting diluted. The Middle East is where Dunya really loses her sense of self. Surrounded by zealous mothers or social media-obsessed socialites, she's unable to fit in, jarred by the normalisation of domestic servitude, scandalised by stories she hears and conflicted about issues such as censorship in this unnamed city swelling with wealth.

For many, expat life in the Gulf is a transient space: not quite home, but home for the moment. A place with a different set of cultural norms, fast-paced lifestyles and uber-high standards – of stature, style, beauty, cars … the list goes on. Dunya feels stifled by the duality of living “in between” spaces, and her sense of self begins to splinter. There’s the western-raised, grounded and humble version with strong humanitarian principles, and then there’s this new personality: a woman in the Middle East, privileged and preoccupied with frivolous matters. She is entirely self-aware about these two opposing selves, and during her flight, dwells on how to bridge this ever-growing chasm in her identity. “At what point did my goals switch from having two degrees to two kids? … When did Net-a-Porter replace BBC News as my homepage?” she wonders despondently.

I often find it difficult to find common ground with female Muslim characters in literature, and wanted to create a young woman who fellow readers could connect with. Dunya’s trials will hopefully resonate with expats in the Gulf who have struggled to form meaningful friendships, women straddling the blurry line between career ambitions and family obligations, and contemporary Muslims who think critically when interpreting matters of faith.

In Dunya, I transplanted many of the inner dilemmas, doubts and insecurities that women of my generation grapple with. What does gender equality look like for modern Muslim women? How can they strike a balance between tradition and the realities of life in the 21st century? Is it ever possible to truly have it all: a successful career, a happy marriage and fulfilment as a mother? I’m a mum myself, and the most alone-time I’ve had over the past few years is on flights, when I’ve travelled solo for work trips. The rare solitude helped me realise that instead of being a limiting setting for a book, a plane provided ample space for introspection.

Dunya doesn’t just travel in seclusion, she travels in luxury. Her business class journey should be a blissful one. But as she gazes at her reflection in the plane window with a mixture of despair and resignation, she contemplates what a documentary based on her life would look like. The turbulence that the title alludes to isn’t physical; it points to the mental gymnastics going on in Dunya’s mind as she is finally forced to confront the realities she has been avoiding.

Multitasking mothers and wives who take on culturally ordained roles and often sacrifice personal ambitions rarely have the chance to acknowledge, yet alone process, the emotional burdens they quietly carry. But, while suspended between these physical environments and societal expectations within the liminal space of a plane, Dunya receives a much-needed reality check. From a higher altitude, she is finally able to view her own situation with an enlightened attitude. This perspective shift helps her make a critical decision that risks upending her comfortable and carefully curated life.

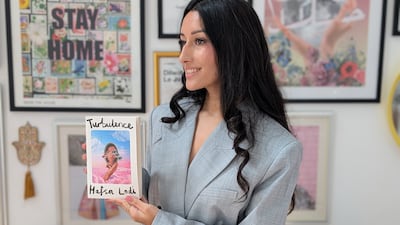

Turbulence by Hafsa Lodi is published globally by The Dreamwork Collective on February 8