"We die. That may be the meaning of life," said Toni Morrison in her Nobel Lecture in 1993. "But we do language. That may be the measure of our lives."

Language shapes us, gives us identity, personality, and a sense of belonging. And there are quite a few languages to "do". In his recent book Babel: Around the World in Twenty Languages, Dutch linguist and polyglot Gaston Dorren notes that there can never be a definitive total of languages spoken because most of them have never been standardised. "Counting the world's languages is as difficult as counting colours," he declares.

That said, 6,000 is the standard estimate, which works out as an average of one language for every 1.25 million people – a veritable babel of voices diversifying and amplifying our modern world.

At the Bodleian Libraries in Oxford in the UK, a fascinating new exhibition has opened that explores the power of translation and its ability to bridge linguistic divides. As co-curator Matthew Reynolds explains, “translation is the crucial go-between in our Babelic world, mitigating the curse-like elements of Babel, and enabling its blessings to bloom”.

Babel: Adventures in Translation, presents a wide range of objects and manuscripts from the Bodleian’s vaults which, collectively, illustrate how concepts, values, beliefs and stories have travelled via translation through time and across boundaries, enlarging our understanding and enriching our culture.

Inside the exhibition

Fittingly, on arrival, the visitor is immediately welcomed by the famous image of the Tower of Babel from the book Turris Babel (1679) by German Jesuit scholar Athanasius Kircher. Fine-lined and multi-detailed, it depicts a feverishly busy work in progress. But the summit, though incomplete, also looks damaged, or torn off, suggesting not construction but destruction.

From here we move on to a selection of early dictionaries: a seminal Latin-English dictionary from 1538; the first single-language English dictionary (Table Alphabeticall) from 1604, with its definitions of "hard English wordes"; and the delightful "canting dictionary" from 1673, a user's guide to criminal slang, which includes terms such as "prigg" for thief, "belly-cheat" for apron, and "bite the roger" for steal the portmanteau.

A section on lost and found languages introduces two artefacts discovered in Crete during a series of archaeological digs in the 1890s. Both date from the second millennium BC, and both feature different writing systems. One is a segment of clay tablet bearing a script termed Linear B, which was decoded in the 1950s and revealed as an early form of Greek. The other is a 3,500-year-old bowl, the script on which, Linear A, has yet to be deciphered. We are brought so close to it and yet it remains out of reach.

How stories are told in different languages

In contrast, in the section on classic children's stories, we see how some writing has been successfully translated and made accessible to all. A spotlight is thrown on one of the best-loved tales, that of Cinderella. Through drawings, pictures, books, theatre programmes and even a glass slipper, we follow the history of the story, from Charles Perrault's moralistic French version Cendrillon, to the Grimm Brothers' more violent interpretation Aschenputtel, and then on to its development in other media such as pantomime and film.

A display of Harry Potter books in various languages (including Latin, Ancient Greek and Braille – just three of the 75 available) shows how translation has played a vital role in the boy wizard's global domination. But rendering an author's brand of fantasy and magic into another language can be a challenge, particularly when invented languages are involved.

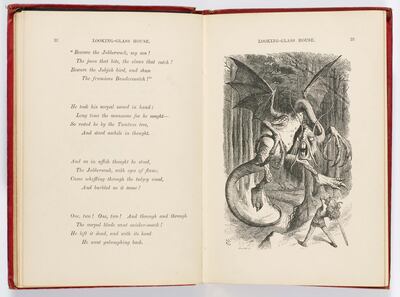

A copy of Lewis Carroll's Through the Looking-Glass lies open at the nonsense poem "Jabberwocky". Not only do Alice and the reader have to make sense of words such as "brillig", "frumious" and "manxome" but translators have to utilise their creativity to conjure up equivalents. Among the other written works exhibited are translations and retellings of Aesop's Fables, Euclid's Elements, and Homer's Odyssey and Iliad (including the so-called Hawara Homer, a second-century papyrus roll unearthed in Egypt).

Elsewhere, a section showcases the languages of the British Isles through a number of texts, from Welsh myths and legends, to Scottish dictionaries, Cornish mystery plays and Irish medieval histories. All serve as a reminder that despite the preponderance of English, the British Isles have never been monolingual.

There are several standout exhibits. The Codex Mendoza, one of the Bodleian's bona fide treasures, is a manuscript composed of colourful, almost cartoonish picture-writing that was created for the Spanish imperial authorities in Mexico in 1541. "This Babelic text gives a vivid impression of the sort of cultural knowledge that it was felt useful for the imperial rulers to have," curator Reynolds says.

Equally vibrant is the 1354 copy of the Kalila wa-Dimna, the influential Arabic version of the Sanskrit Panchatantra, a collection of animal fables. One beautiful illustration doubles as a succinct cautionary tale: a greedy, opportunistic jackal approaches a pair of fighting rams but gets too close for comfort.

Most resplendent of all is a sixteenth-century Quran that once belonged to Tipu Sultan, ruler of Mysore in southern India. It is exquisitely intricate, a sumptuous fusion of words and designs. “Woven into the complicated pattern is the verse of the Quran, which asserts its inimitability,” explains Reynolds. And, for many, its untranslatability.

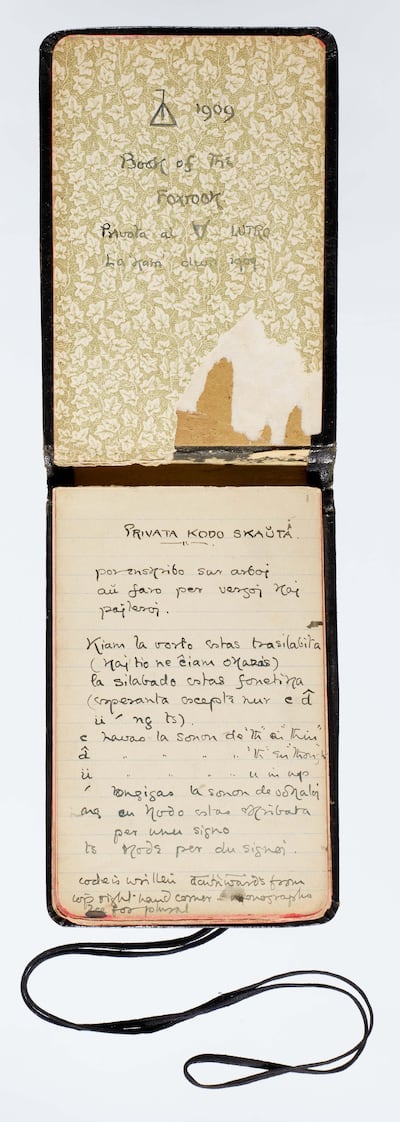

Babel: Adventures in Translation manages to be both edifying and entertaining. Even the smaller, seemingly insignificant curios pique our interest or prompt a smile: an unpublished notebook containing J R R Tolkien’s first forays into invented languages; a crash course in urban sign language; a 1950s computer program that generated love letters; plus Franglais sketches, Esperanto newspapers and bilingual road signs. A final, more sobering section abandons the past and the present and looks a hundred millennia into the future to ask how we might intelligibly warn our distant descendents about the locations of buried nuclear waste.

Whether our languages will last in tomorrow’s world is anyone’s guess. For now, in these disjointed post-truth times, this is a welcome exhibition that celebrates shared understanding.

Babel: Adventures in Translation is on show at the Bodleian Libraries in Oxford until June 2. For more information visit

www.bodleian.ox.ac.uk