When she was in art school, Alaa Edris snuck into the university's men's bathrooms and put up mirrors behind the stall doors while her friends stood guard outside. She did the same in the women's, across 16 cubicles. "My classmates thought it was funny," she remembers. But this wasn't a prank. It was an art installation.

For Edris, the intervention was a way to push people into self-reflection, to confront themselves in unexpected places. Above the mirrors, she pasted stickers with a passage from Lewis Carroll's Alice's Adventures in Wonderland, including questions such as "I wonder if I've been changed in the night?"; "Was I the same when I got up this morning?"; "Who in the world am I?"

The stunt didn't go down well with the administration team at the University of Sharjah, and the artwork was destroyed. Almost a decade later, in 2017, Edris would revisit this work – this time with permission – through a commission by Abu Dhabi Art. Instead of mirrors, she hung up reflective TV screens in the Manarat Al Saadiyat bathrooms. As visitors sat down on the toilet seat, the sensors would be triggered and Edris' face would pop up on the screen, reciting Alice's lines. Thankfully, the work – named The Great Puzzle – survived.

Born in Dubai, raised in Sharjah and living in Abu Dhabi, Edris has been developing her practice for the past 13 years. She was a Salama bint Hamdan Emerging Artists fellow and the only Emirati artist who participated at this year's Sharjah Biennial 14 in March. Recently, she opened her first solo show at 1x1 Art Gallery in Alserkal Avenue, which runs until the end of the month.

It is a compelling show – titled Unreal. Unseen. Untouched. – and a brilliant display of the ideas that Edris considers in her work. Selfhood is one, but also the tension between the public and private, the division between the visible and hidden, the authentic and false.

The Great Puzzle makes another appearance for the exhibition, and I discuss it with Edris when we meet at the gallery during the installation. The humour of the work isn't lost on her, she says, adding that she likes the contrast of contemplating the existential as one fulfils a "biological urge".

We talk about the intrusive nature of the work, and the resulting discomfort when subconscious lines of privacy are crossed. “The space becomes this theatre where the person is an audience of one, looking at this performance with this uncomfortable feeling of ‘why am I being forced to watch this?’ because there’s no way out of it,” she explains.

Layers, faces and masks – Edris was drawn to these motifs out of convenience rather than choice. "Being an Emirati, growing up in a conservative society and conservative home, the face was a natural choice for me. I had my face, and that got me thinking that your face is like your perception … It's the facade that you present to the world."

This veneer is a tool that’s available to all of us, and we can adjust it as we see fit. “We have all these different faces and every single one of them is something we have to put on. We’re never really us. It’s always a face – my face with you right now, my face with my family, my face with different people,” she says.

Growing up, Edris often drew and painted, but it was photography that really brought her into art. She tells me she’s a “photographer at heart”. It started in middle school, when she got her first digital camera. Though images from that time are now lost, she remembers going on trips to the mountains with her family and taking photographs of dead animals, abandoned places, and “broken things”.

But a career in art was never really a consideration, for many reasons. Back then, the UAE art scene still had a long way to go. There was also her family’s conservatism. It wasn’t until a friend took her to visit the fine arts department at the University of Sharjah that things changed. “It’s like I had this epiphany. I went home and I told my family, ‘I’m changing majors. I want to do art.’ I don’t know what happened to me. I was possessed by an art demon, I guess,” she says.

With her likeness as her material, Edris' work instantly becomes personal and performative, as we see in The Consumer, The Consumed – Ignorance and Wants, a pair of two-channel videos that juxtapose the artist and two loaves of bread with the Arabic words for "ignorance" and "wants" carved into them. With a gloved hand, Edris plunges a knife into the bread, cutting out large pieces that she eats while looking directly into the camera. Consuming without pause or taking a sip of water, tears begin to well up in her eyes. You can almost feel the abrasion in your throat, but the most striking thing about the scene is the compulsiveness of the consumer's behaviour. It is automatic, and it is torture that she inflicts on herself.

Eating becomes symbolic of what the artist calls "the deteriorating process of thought". What do we thoughtlessly and continually consume to the point of our own detriment? The videos, each a little over five minutes, play on loop – a cycle that never seems to break.

In The Seven Jinnat of Trucial States, Edris transforms her face – and by extension her identity – completely, using digital photo manipulation to take on the forms of seven djinn or spirits from Emirati folklore. In one story, grief turns a mother into an owl (Al Naghaga) after she loses her son, leaving her to roam a Sharjah neighbourhood after sunset, looking for someone to possess or devour. In another, Umm Al Hailan, an old woman is seen as a bad omen. "If she visits your house then you're cursed. Somebody dies. Your husband divorces you. Or something bad happens," Edris says.

These narratives shaped much of her childhood, and the childhood of many other Emiratis. "They're very telling of societal norms," says the artist, who is drawn to the fact the most powerful djinn are female, and wonders how these folk tales carry over into everyday perceptions as adults. "These stories help shape generations and cultures," she adds.

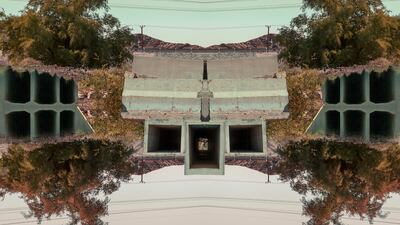

If humans can put on a presentable face, then so can architecture. Through a series of digital collages, Edris investigates these urban facades and reimagines them by playing with scale, colour and repetition. In States, elements from the UAE's architectural landscape are dissected and flipped into pastel and neon reconfigurations, rendering these places alien, something out of a sci-fi film set. In Reem Dream X, Edris turns her lens not to the skyscrapers, but the unseen parts of Al Reem Island – pillars, passageways and sandpits fill these dystopian visuals that become the antithesis of developer brochures.

These urban reimaginings can also be seen in The Black Boxes of Observational Activity, which was initially presented as a site-specific installation at the Sharjah Biennial 14. Placed on a rooftop, the boxes faced out to the four cardinal directions. Visitors could look at the "real" view, and then peer into the box to see Edris' reconfigured view, where buildings were rotated and stacked, and the sky tinged with surreal pastels.

The continuity of ideas from earlier works can be seen here, including the erosion of the division between public and private space as surveillance technology spreads globally. Acting as a kind of surrogate for these systems, Edris captures footage of daily life as CCTV cameras do – a woman hangs his clothes on the balcony, a truck passes, a lounges on a chair.

Inside the gallery, her large-scale multimedia work The Face combines this with the idea of facade. Hung on a wall is a face-shaped cast on to which a video projection plays. It is Edris, or rather, an avatar of hers that looks more machine than human, her eyes casting around the room. "The work started as a self-portrait, and naturally evolved into this all-seeing authoritative face that asserts its existence and presence in the world," she says.

This is part of what makes Edris such a strong artist. She takes risks. She asserts herself – her face, identity and ideas – in unconventional and potentially controversial ways, but remains uncompromised. "I want everyone to see my work, but I also want to be able to say what I want to say in my own way, with elements that are true to me and my practice," she says, adding that she has been removed from certain shows in the past.

Her work is at times esoteric, often sinister and a little unnerving. But it’s almost always original.