In 2005, Mitra Farahani, then 30, visited the Parisian home of exiled Iranian abstract painter Behjat Sadr, 81 at the time, to make a film about her pioneering life and uncompromising career.

After a lifetime on the margins of Iran’s modern art scene, Sadr had finally been recognised with a major retrospective at the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Arts the year before, and despite an age gap of 51 years between the filmmaker and her subject, the pair obviously gelled. Their very personal collaboration resulted in a 46-minute-long documentary, released just three years before the artist’s death in 2009, which now acts as a kind of postscript to Behjat Sadr: Dusted Waters, the first solo presentation of Sadr’s work in the United Kingdom, curated by art historian Morad Montazami.

As well as a scholar of art history, Montazami is a publisher and Tate Modern’s adjunct research curator for the Middle East and North Africa. The most telling scene from the documentary, a canvas-eye view of Sadr in action, is shot through glass from below in a way that recalls Hans Namuth’s short film of Jackson Pollock painting in 1951. In it Sadr pours viscous, oil-coloured paint onto a sheet of glass, which she then moves and shapes with a palette and ink knife until she achieves the desired effect, reminiscent of an oversized Roy Lichtenstein brushstroke.

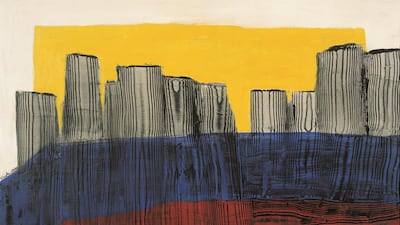

Both the motif and the material recur throughout Sadr’s career, at some times looking like the bark of a tree, at other’s like a form of meaningless, abstracted calligraphy, pure mark-making achieved using the same combination of hand, eye and breath. Towards the end of her life, the streaks assume a portal-like function when they were used to frame archetypal, placeless landscapes in what the artist described as photo-collages – combinations of photography and painting that echo the various phases of her life and career in Tehran, Rome and Paris.

An exhibition in three parts, moving through the cities that had such a formative influence on her life, Dusted Waters uses a combination of key works alongside archival material, film, contemporary publications and photographs to chart Sadr’s remarkable trajectory.

Early life

Born to a conservative family in Arak, the capital of Iran’s Markazi Province in 1924, Sadr began studying painting in 1948 at Tehran University and on graduating in 1954 won a major scholarship to study in Italy at Academia in Rome and Naples. It was in Naples that Sadr met and collaborated with the influential art historians and critics Giulio Carlo Argan and Roberto Melli, who became her mentor and whose introductions to gallery owners and influential critics led to Sadr being selected to represent Iran at the 1962 Venice Biennale. She also exhibited at the Tehran Biennale in 1962 and 1964, as well as the Musee d’Art Modern de la Ville de Paris in 1963.

Sadr’s work was well received, with numerous Italian and French critics praising her directly, including Pierre Gueguen, a champion of French abstract painting, but she returned to Iran and to the University of Tehran where she taught for almost 20 years, and where she was the first Iranian female artist to become a professor at the university’s Faculty of Fine Arts.

Always a figure at the forefront of Iranian modernity, Sadr was nevertheless marginalised as a result of both her gender and her work and she occupied a position at the fringes of the generation that included Hossein Zenderoudi, Parviz Tanavoli and Monir Farmanfarmaian. Her unapologetically abstract work eschewed the Neo-traditionalism of the now famous Saqqakhaneh School and all notions of Persian symbolism, and instead tackled the major issues of her time head-on.

Creating oil-based textural paintings that might be understood as petrochemical landscapes, Sadr was one of the few Iranian artists to deal directly with the contradictory forces that made her career and education possible, namely Iran’s tremendous oil wealth and the ambitious cultural aspirations of its ruler, Mohammad Reza Shah and his Empress, Farah Pahlavi, whose patronage not only resulted in the opening of Iran to the international art scene but to the establishment of the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art in 1977.

Insider her artwork

"Behjat Sadr's obsession with oil came from the realisation that this artistic soft power, sponsored by the Shah and the Empress, was creating an environment in which the elite chose which artists should be highlighted," Montazami says.

“What she does with this metaphor of oil was a way of being part of the system while at the same time challenging that system. She saw blackness more as an experimental space rather than as a symbolic colour,” Montazami tells me.

“The colour becomes more like a texture that you can experiment with. She wanted to create art that was more shocking and provocative than beautiful.”

Sadr's often irascible personality and uncompromising stance stood in stark contrast to the ostensibly decorative and acceptably apolitical form of modern art that was favoured by the court. "I did not profit from international exhibitions organised thanks to oil money. And when a gallery owner proposed coinciding my opening with the visit of Empress Farah Diba [Pahlavi], I was annoyed," Sadr wrote in a diary from the 1990s.

“Was it sincerity or foolishness? I did not use calligraphy or Iranian motifs in my canvas to stimulate national pride among my compatriots or the curiosity of strangers. This was the cause of my downfall, but I don’t mind. I did not seek the protection of a man to advance and achieve success.”

Behjat Sadr Dusted Waters is the second exhibition in a three-part series curated by Montazami to be held at London's The Mosaic Rooms, which are collectively entitled Cosmic Roads: Relocating Modernism. "The idea is to highlight important figures from Asian-Arab modernities, but figures who for personal, political or aesthetic reasons were already viewed as artistic mavericks in their own time," Montazami explains. "These artists could have been highlighted in their own time. They were part of a certain movement, they all travelled a lot, but they were also resisting certain conventions of the official modernities that were established by the biennials at the time and by different regimes and governments."

________________________

Read more:

Rembrandt's 'The Night Watch' to be restored under public view

British Museum's new gallery shows the influence of Islam in the Middle East and beyond

Thousands queue to view shredded Banksy: who is the controversial street artist?

________________________

As well as curating Behjat Sadr: Trace Through the Black at the Ab-Anbar and Aria Galleries in Tehran in 2016, Montazami was also responsible for acquiring an untitled 1967 work by the artist for the Tate Modern collection in 2017. The curator describes these efforts as attempts to “find a place” for Sadr in a reconsidered history, not just of Iranian Modernism, but of post-war Modernism as a whole, and in doing so, he has joined a long and illustrious list of critics and curators who have fallen under Sadr’s spell.

On the strength of the work displayed in Dusted Waters, Sadr’s belated place in this new canon seems not only to be ensured but entirely justified. Not least for her fearless dissection of the effect of oil on the art scene in an older and very different Middle East.

Behjat Sadr: Dusted Waters is at The Mosaic Rooms, London, until December 8. For more information, visit www.mosaicrooms.org