Daniah Al Saleh's studio is in a former converted warehouse along a west London canal. The site epitomises the gig economy, with shared desks, talkative 20-somethings and overpriced coffee. But tucked off the main drag, the Saudi Arabian artist's workspace reveals a different story, one in which the path towards being an artist was not a given, and in which Al Saleh had to cobble together time and opportunities to make her artwork.

Following her passion

Born in Riyadh in 1970, Al Saleh studied computer applications at King Saud University. But her real passion was art. “It is the usual story of an artist,” she shrugs. “I loved painting and drawing from a young age.”

When she moved to Jeddah to start a family, she took art classes at the Darat Binzagr, the informal art school that the artist Safeya Binzagr set up in her home. "When I went to Jeddah I craved painting, like the paintings I saw in galleries and exhibits. I didn't know how because I never learnt – I doodled, I tried to imitate, but I didn't know the structures.

“There wasn’t the internet back then, and the only exposure I had was when I travelled with my family during summer breaks. When I heard that Safeya Binzagr had an art programme I jumped on it.”

There, as for many artists of her generation, Al Saleh was taught by Binzagr and the Scottish artist Dorothy Boyer, a watercolourist who had settled in Jeddah for decades with her family. "Dorothy was very kind and generouswith her knowledge," Al Saleh says. "That was also when the internet started, so I would stay for hours and hours on end looking at art online, registering for courses, planning my summer breaks around them – Saint Martins, the Slade, the Art Academy, many at the Prince's Trust. But I could only do short ones because my kids were young at the time."

Two decades on, Al Saleh has won the second Ithra Art Prize, the award given by Art Dubai and the King Abdulaziz Centre for World Culture (Ithra) in Dhahran, near Dammam. It comes with a $100,000 (Dh367,315) prize that goes towards the production of an art work, which is exhibited in the main halls of the Dubai art fair and then enters the permanent collection of the grand Ithra art centre.

Her winning entry

Al Saleh won the prize for her proposal, Sawtam, a digital demonstration of how meaning in Arabic is formed. Al Saleh isolated the basic element of communication: the phoneme, or "sawtam" in Arabic.

"The smallest item is the pronunciation of the word, the phoneme," she explains. "I'm very interested in things that go unnoticed: the mundane, the ordinary things of everyday life, and language is one of them – we take it for granted. I looked at language and thought, what is it? It is the spoken word: wind, the movement of our tongues, and the sounds that we make through our mouths."

Al Saleh wrote a computer code that changes the lines on a monitor when each of the Arabic language’s 28 sounds are voiced. Each sound is displayed as almost a dance of lines on one of 28 monitors which are stacked seven high in four rows. “I made a small sketch in programmable code that generates the abstract image of geometrical lines that move, that are in rotation,” she explains. “When combined with the sound file, the lines vibrate like a sound wave. The analogy is a wind chime that’s moving in the breeze. A strong wind blows and it moves faster and it comes down. That’s the abstract idea I had – and I translated that into a visual installation.”

The transfiguration of sound into visual art has a long and important art history. Ibrahim El-Salahi's painting The Last Sound, from 1964 (and which is on view at the Barjeel galleries at the Sharjah Art Museum), considers the last sound the world might make: a perfect black circle; thing, spindly grey emendations; a water red stain. In the early days of cinema, the visual representation of sound proved a particularly alluring subject, as film could represent sound, vision, and time at once.

Mary Ellen Bute, a little-known American avant-garde filmmaker, made choreographies of lines in the 1940s in order to visually represent music. Rather more famously, Fernand Leger made the film Ballet Mecanique in 1924, in which everyday sounds and the workings of film itself combine to create a cinematic syncopated rhythm.

It's unclear how much Al Saleh alludes to this tradition, but her work shares a spirit of testing out new technologies. Al Saleh, after years of ad-hoc art scholarship, has enrolled in her first formal art course, in computational art at the renowned institution of Goldsmiths, University of London.

"I am so thankful that I am on this course," she says. "I have learnt so much that I wouldn't be exposed to. This is the movement now. Instead of sitting in a studio with my brush and paints contemplating light, waiting for creativity to strike, this has opened whole new doors for me with possibilities. It's endless!"

Overlooked geometries

If Sawtam is a break from the kind of work she was making before, it still contains the same germ of analysis: the desire to focus on what is elsewhere overlooked. "I used my work to show some sort of narrative," she says about the geometries she makes in watercolour, which she has continued alongside her work in new media.

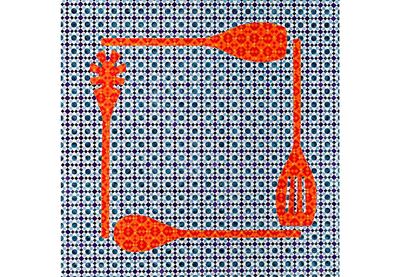

She painted wooden cooking spoons as a kind of interior frame within one work. "The painting is not about wooden spoons, but about something much deeper," she says. "You use a wooden spoon to cook your meals, but do you bring it out at a dinner party? I used it to show how the normal person who works hard from nine to five goes underappreciated, even if they are the main support of the society."

Like many Saudi artists of her generation, she critiques aspects of Saudi Arabian society, while at the same time celebrating its folkloric and religious history.

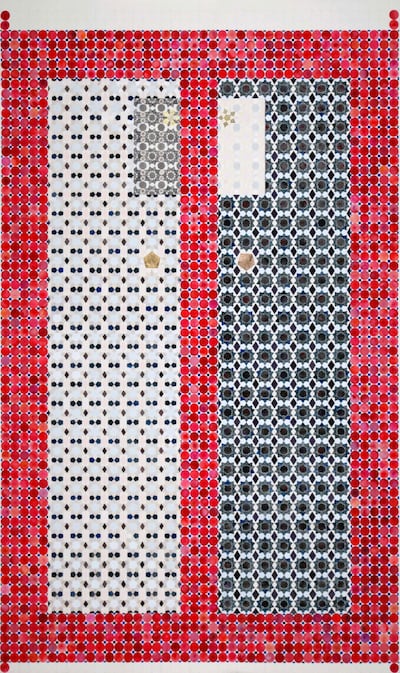

With Ahwak, for example, the work she exhibited in 2014 at the first 21, 39, the yearly Jeddah arts festival, she told a "Saudi love story". The geometric painting contains two rectangular forms made out of differently coloured patterns.

"Ahwak means, roughly, 'I love you' – or even, above love, 'I'm passionate about you'," she explains. "The love poems on the Kaaba … would mention the names of their lovers, and how they met them, and describe how she looks and how beautiful she was. For me, this is a celebration of poetry."

Al Saleh says the challenge for her now is to combine her painting with the forms of expression she is learning in new media arts. "I'm still testing things out," she says. "I just need time to realise my ideas. That's all."

Daniah Al Saleh's prize-winning work Sawtam will be on display until Saturday at Art Dubai, Madinat Jumeirah. For more details, visit www.artdubai.ae/the-fair