There is nothing to suggest that an art studio is hidden somewhere on this nondescript street in Riyadh. There are no signs welcoming visitors, or windows to peer through. But enter a small door cut into an imposing wall and you find yourself on a pathway leading to a brightly lit collection of rooms.

As you approach, you pass major pieces of contemporary Saudi Arabian art. On the left is a large pink canvas by Njoud Alanbari; on the right a monumental wire structure – a mosque of sorts, or is it a cage? – by Ajlan Gharem sitting on top of a swimming pool. At the end of this pathway, Abdulnasser Gharem, brother of Ajlan and father of contemporary art in Saudi Arabia, waits to greet us, shaking our hands warmly and ushering everyone inside.

This is Gharem Studio, a non-profit arts organisation founded in 2013 by Abdulnasser and Ajlan, where young Saudi artists can come to learn, create and generally just hang out. "It is a space where artists can be true to themselves," explains Ajlan on his website. "I want [the studio] to act as a guide for everyone who utilises it to come up with ideas and initiatives."

Inside the studio

There is certainly a bohemian feel here at odds with Riyadh’s conservative reputation. The main room is stacked high with books about art. “Every time we travel, we bring back a huge suitcase full of books,” the creative director of the studio, an artist known as Shaweesh, tells me. “We spend thousands just on shipping.”

One of Abdulnasser's paintings dominates the back wall; another of his artworks, part of a series of oversized wooden stamps, rests just in front, so absurdly large it messes with your sense of perception.

There is stuff heaped everywhere: coats, bags, plastic action heroes, skateboards and newspaper clippings jostle for space on every available surface. A further four rooms, only slightly more ordered, are used for making and displaying art. Gharem Studio is a place free from constraint.

“We are brainstorming every day,” says Abdulnasser. “In Saudi, it’s still difficult to talk about contemporary art … I hope we’re going to develop the art centres and the libraries to help build relationships with other institutes. We need to send our students abroad to study art, music, poetry, theatre … everything.”

The artists

There are currently 11 artists – men and women – in residence at Gharem Studio. Abdulnasser, 45, a former lieutenant colonel in the Saudi Arabian army, is their financial backer and mentor, always ready to prod them into thinking differently. “What we are doing here is trying to help the artists to focus on the DNA of their culture,” he says. “They need to dig into their heritage … If you want to be different you need to rely on your cultural sources, your mythology, everything that belongs to you. We don’t want to copy others.”

Shaweesh adds: "When young artists come here, most of them are lost. There's a lack of knowledge, they don't know the difference between what they belong to and what they love." Shaweesh, one of the Gharem Studio's success stories, shot to fame in 2017 when he superimposed an image of the Star Wars character Yoda onto a 1945 photograph of the late King Faisal of Saudi Arabia. The doctored image was then accidentally included in a school textbook. The page from the book hangs on one of the studio's walls.

The young artists here could hardly be in better hands. Abdulnasser is the man behind some of the most important contemporary art to have emerged from this region in the last century. He has had solo shows in Berlin, Dubai, Los Angeles and London. In 2011, he became the most expensive living Arab artist when Message/Messenger, a vast wood and copper dome concealing a stuffed white dove inside, sold for $842,500 (Dh3 million) in Dubai. Abdulnasser donated the money to Edge of Arabia, an independent arts initiative, in order to fund the development of 32 Saudi artists. "These artists are now on the scene," he says. "Turn people onto the right track and the results will be amazing."

Inspiring a new generation

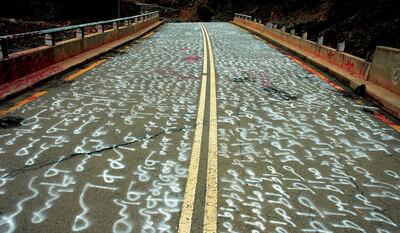

Abdulnasser, who was born in 1973 in Khamis Mushait, a conservative town in south-west Saudi Arabia, gained the attention of the art world in 2007 on completion of his work Siraat (The Path). He spray-painted the word "siraat" or "path" (repeated 34 times a day by Muslims in prayer), on to a bridge in south-western Saudi Arabia that a group of villagers gathered on in 1982 when the rains came, to save themselves from an approaching flood. Instead, the bridge that was supposed to protect them collapsed and killed most of them. What does the work mean? "This is the path – is it something you'll find and follow or is it something you'll leave behind? I think it's an important question," says Abdulnasser.

In 2007, he took his art directly to the streets of the city of Abha, wrapping himself in a plastic sheet with a species of tree imported from Australia, which was killing the native trees in Saudi Arabia. Flora and Fauna, says Abdulnasser, made him realise "how art will affect people".

“In the beginning, people thought I was crazy, but after a while they started to talk to me,” he says. “That’s your job as an artist: to start the dialogue. No-one knows where that dialogue will go … I don’t need a gallery, I’ll just go to the streets and talk to people.” Having seen Abdulnasser’s work, many people called on the authorities to remove the dangerous trees.

Images from another of Abdulnasser's performance work, Traditional Pain Treatment, occupy another room of the Gharem Studio. In it, an artist with a map of the Middle East tattooed on his back goes through a traditional method of bloodletting called hijama. Hot glasses are placed on cut skin, which draws out the blood. "We need to take the bad blood from all the countries," Abdulnasser said in a 2016 interview with the United States's National Public Radio. "The bad ideology, the bad politics, the bad economics. Everywhere."

Even as night falls over Riyadh, Gharem Studio remains a hive of activity. Computers whir and the artists continue to cut and chop and stick and paint. Abdulnasser thanks each of us individually at the door. As I leave, I'm reminded of something he said earlier in the day: "We want people who are free thinkers because we want them to support society with ideas." At Gharem Studio, Abdulnasser is rounding up the free thinkers – and the results are already proving to be extraordinary.

For more information, visit: www.abdulnassergharem.com