Newly-weds sit on the hood of a nineties Mazda coupe; its windshield decorated with a "Just Married" sign. The couple's pose doesn't seem strange at first. They seem a bit distant from one another, sitting half a metre apart and looking at their smartphones. The bride has a bouquet in her other hand and the groom's smoking a cigarette. Maybe they're taking a break from the day's wild celebrations on their way to the honeymoon, but then you see their phones are not there, notice the unnatural form of their empty hands, and the strangeness of the scene strikes.

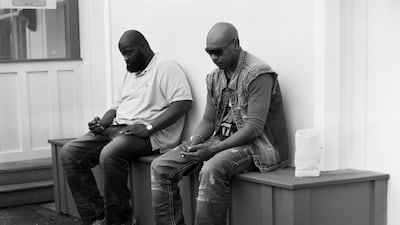

The phones were purposely removed by American photographer Eric Pickersgill. In a series titled Removed, the photographer presents 43 black and white photographs that show just how much we are enveloped by the contents of our screens. The photos have since gone viral and seem to have touched a collective nerve, articulating how removed from our immediate world we've become in an effort to always stay connected.

Pickersgill says that the idea for the photo series came when he was sitting in a New York cafe. "There was a family sitting on the table next to mine. The father and the two daughters had their phones out. The mom was without one. She was staring out of the window, looking sad and alone, even though she was in the company of her most loved ones," he reveals.

It wasn't long after that Pickersgill completed his New York artist residency and reunited with his wife in North Carolina. The two were together in bed one night, on their phones and with their backs to each other, when the photographer fell asleep.

"The phone slipped out of my hand," he tells me. "I woke up to see the awkward form of my hand without the phone and I remembered that family in the cafe. That's when the idea for the photo-series came to me."

One of the photos in the series recreates that moment. It shows Pickersgill with his wife, his back to hers. Both are intently focused on where their phones are supposed to be. Their hands cupped awkwardly.

“If you look closely at the photograph, you’ll see my right hand covered by the bedsheets,” Pickersgill says, adding that he used a remote control apparatus to take the picture. “I wanted to make it a point to be in the photo-series as well. I don’t want to come across as a boomer, who is disdainful of technology,” he says, adding that he is just as guilty of spending too much time on his phone.

He doesn't use a conventional digital camera for the photos he takes. He prefers a large-format camera, the kind with an accordion-like body and a blanket. He favours it because the quality of the photographs is much better, adding texture and tonal range to the images, he says. It also makes for an excellent icebreaker.

"Film is quite expensive," he says. "I have to think about the shots in advance, be less sporadic and focus on the overall composition. Using a large-format camera forces me to plan ahead, to slow down."

But Pickersgill doesn't Photoshop the phones out of the pictures, he takes them away during the shoot. For him, his subjects are performers and the photo shoot is a collaborative endeavour.

“In fact all of the photos are performances. The people in them are like hired actors. I don’t want to use Photoshop to remove the phones. I want people to have those experiences with me.”

Pickersgill's love for film photography goes back to his days as a high school student, where he had access to a dark room. He found the science of developing photos and "the magic of being under the red light" alluring. Some of his earliest adventures as a photographer had him touring with punk bands and BMX teams. The camera, he says, gave him a sense of identity.

But in 2008, when the American housing market was hit by the financial crisis, thousands of homeowners were forced out of their properties and that's when the photographer did a series called House Sitters. The series documented one of the stories to come out of that crisis, and that's of the individuals who were allowed to seek shelter in living rooms of homes acquired by foreclosures. This was done as a way to make properties appear occupied and prevent them from vandalism.

"After that photo series, I kind of became frustrated with photography. I was asking myself who was profiting from the images. It kind of felt exploitative," he says.

He later went on to teach science in high school via Teach for America, an experience he says changed the way he saw the world. That's also when he met his wife, with whom he has a 3-year-old child. His return to photography came at his wife's insistence.

"She asked me 'weren't you an artist?'" he tells me. "I went to do my Masters in Fine Arts at the University of North Carolina after that."

Pickersgill has exhibited and presented his work internationally at institutions, galleries, and art fairs such as The North Carolina Museum of Art, Pantheon-Sorbonne University, and the World Economic Forum in Vietnam. He has also spoken at TEDx in Paris and the United States, where he asks the very poignant question: "Do our devices divide us?" The answer lies in the photos.

To view more of Pickersgill's work, visit www.removed.social