“I cried today over the death of a loved one,” writes Afghan filmmaker Sahraa Karimi on Twitter. The “loved one” she refers to is Cinema Park, a 70-year-old cinema in Kabul that was demolished by Afghan authorities to make way for a new development this month.

"I am a film director; every movie theatre is my home," Karimi's statement continues. "The house in front of my eyes was destroyed and I just cried. I apologise to all the filmmakers, the citizens of Kabul, the people of Kabul. I could not stop the destruction of Cinema Park."

A video of Karimi weeping outside the ruins of Cinema Park has been making rounds on social media since early November, when the filmmaker protested inside the building in an attempt to stop it from being razed.

Karimi was among a number of film directors, artists and activists speaking out against Cinema Park's demolition, citing it as a significant landmark in Afghanistan's cultural history. Filmmakers such as Salim Shaheen and Mohammed Nabi Atai have also expressed their disapproval of the decision, with Atai stating that the building should be considered a historical site.

On social media, users shared the same sentiment with a corresponding trending hashtag, “#Don’t_destroy_cinema_park”.

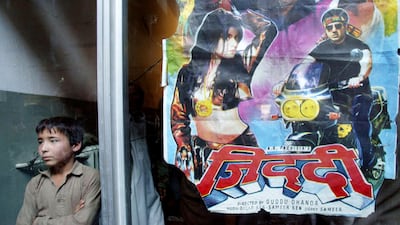

In its golden age between the 1960s and 1970s – when Afghanistan was making great leaps towards modernisation and liberalisation – the cinema played Hollywood, Bollywood and Afghan films to audiences of both men and women. Built in the 1950s, it managed to survive the invasion of the Soviets in 1979, but underwent significant damage during the consequent Afghan Civil War and was eventually shut down during Taliban rule.

Despite reopening after the fall of the Taliban in 2001, Cinema Park failed to secure any investment. The building, still scarred by bullets and bomb attacks, further decayed from neglect, even though it continued to show up to four films per week. In its last week, the cinema hall had about eight employees. Authorities, however, saw the venue as a shelter for drug addicts and continued to call for its destruction.

First, Vice President Amrullah Saleh ordered the demolition that was carried out by Kabul Municipality on November 9. The following day, Saleh addressed critics in a tweet, asking them to support the government's new plans for the area.

"I am impressed with the amount of love and attachment some show to cinema and the art of film. I invite them to make intellectual and other type of contributions to the architectural concept that we are developing to replace the demolished one," Saleh wrote, adding the cinema hall was a "broken building" from the 1960s that was "of no use".

However, activists have questioned the decision to tear down Cinema Park rather than preserve its history. Afghan politician and parliament speaker Mir Rahman Rahmani said in a statement, as reported by local news channel TOLOnews: "Destruction of homes, the destruction of Cinema Park and booths is carried out under the guise of bringing reforms."

This month, TOLOnews obtained a copy of a contract revealing that companies had been bidding to erect businesses in Shahr-e Naw Park, where Cinema Park is located, which contradicts statements by Kabul Municipality that it had received no project proposals for the site.

The document, dated 10 months ago, shows the government was offered $38 million to lease the park for 40 years, with plans to transform it into a venue with restaurants, markets and an entertainment centre. The money would be split among the Ministry of Finance and Kabul Municipality. The former claimed to be unaware of the report.