There are more than 600 artworks and artefacts in Louvre Abu Dhabi's extraordinary permanent collection. Some of these stand out immediately.

The magnificent statue of Egyptian pharaoh Ramesses the Great, who ruled the New Kingdom from 1279-1213 BC, sits imperiously in the centre of a vast room, surveying the crowds that continue to flock at his feet.

Elsewhere in the museum, people clamour to get a peep at Leonardo da Vinci's La belle ferronniere (1495-99), Vincent van Gogh's Self-Portrait (1887) or Mark Rothko's No.14 (Browns over Dark) (1963).

But if you’re willing to take a slightly different route and explore the less well-visited corners of the museum’s 12 galleries, you’ll find any number of hidden treasures with their own stories to tell. Coins and pots and dusty-looking ceramic fragments – these are the items we tend to rush past, forgetting that the least conspicuous things often hold the most exciting secrets.

With that in mind, I have selected 10 pieces from the jigsaw of Louvre Abu Dhabi’s collection that warrant a closer look. Some of them are of real historical significance; others come with almost no information at all, which only adds to the intrigue.

Perhaps you’ll be familiar with a few of these already, in which case I hope this list inspires you to do a bit more of your own digging the next time you’re there.

1. Reliquary casket with the Three Magi, Limoges, France (c.1200)

The Grand Vestibule, where your journey through Louvre Abu Dhabi begins, is not just an appetiser. Spend time here – this room holds the key to understanding what comes next. It is crammed with items spanning religions and ages, from hand axes to gold masks, which invite us to consider the birth and progress of human civilisation as a universal endeavour.

And what could be more universal than death? This intricately crafted reliquary casket from the 13th century, which would have housed fragments of bone or clothing belonging to a Christian saint, sits alongside an urn from Italy (600 BCE) and a portable temple from Fiji (before 1900). As the museum guide notes: “The living need the dead in order to inscribe their short lives into the long history of their community.”

Christian pilgrims would travel many miles to see a reliquary casket such as this one, which depicts scenes from the New Testament story of the Three Kings. The vibrant blue and gold casket is designed using a technique called champlevé, which involves carving shapes into a metal surface, filling them with coloured enamel or powdered glass and then heating the metal until the substances fuse.

Where to find it: The Grand Vestibule

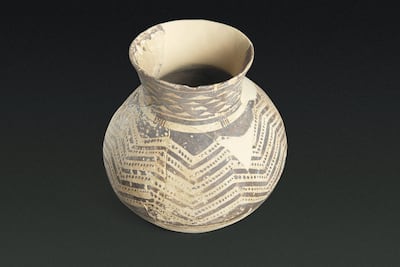

2. Vase with geometric decorations imported from Mesopotamia, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates (c.5500 BCE)

Discovered in a Neolithic settlement on Marawah Island, off the coast of Abu Dhabi, this vase is the oldest piece of pottery ever found in the UAE – but it originated in the south of Mesopotamia and bears all the hallmarks, including chevrons and broken lines, of the Obeid culture (6500-3800 BCE). So what was it doing here, almost a thousand kilometres from where it was made? This vase appears to prove that maritime trade was taking place in the Gulf much earlier than previously thought.

Where to find it: Wing 1, Gallery 1 (The First Villages)

3. Chinese coins, 600-200 BCE

Money in the form of metal coins is thought to have first appeared in the 7th century BCE in the kingdoms of Asia Minor. The history of these small objects – whose influence on humanity cannot be overstated – is told in a gloomy little room in the corner of Gallery 2. It is easy enough to miss it but seek it out, for there are treasures here from across the globe including Greece, India, Rome, Turkey and the UAE. This room also has one of the best interactive experiences in the museum, allowing visitors to see magnified images of each individual coin.

Of particular interest are a set of bronze coins developed in China from the 6th century BCE onwards, which come in a variety of shapes, including knives and spades. In 221 BCE, the emperor Qin Shi Huang began to standardise coinage and established a single legal coin denominated in terms of its weight. It was round with a hole in the middle to allow large numbers of coins to be strung together.

Where to find it: Wing 1, Gallery 2 (The First Great Powers)

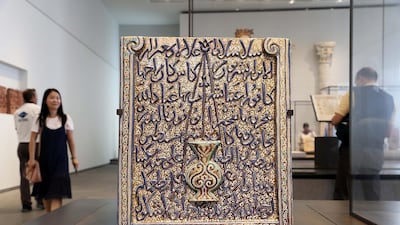

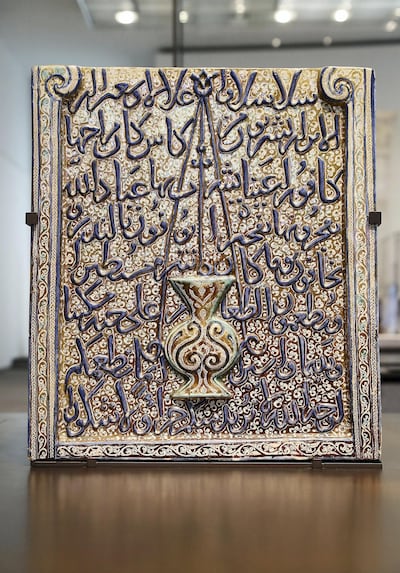

4. Fragment of a plaque in the form of a mihrab, Central Asia, 1250-1350

There is very little historical information accompanying this large broken slab of lusterware depicting a mihrab (the niche in the wall of a mosque indicating the qibla or direction of Mecca) but it really doesn’t matter. Instead, you should just bathe in the deep blues and turquoises, which shimmer beneath a metallic glaze, and marvel at the elaborate swirls decorating the central lamp (a reference to the Quranic surah about light).

Amid all the dates, the names and the facts in a museum of this size, here is a gorgeous piece of Islamic art to be enjoyed without context. Feast your eyes – and don’t feel guilty.

Where to find it: Wing 2, Gallery 4 (The Universal Religions)

5. Bactrian horse, Tang dynasty, China, 700-800

The development of the “Silk Roads” – terrestrial links between Asia and Europe – led to a centuries-long trading of ideas and artistic techniques across continents. One of the earliest beneficiaries of this was the Chinese empire of the Tang dynasty (618-907), which imported many exotic products, including glass, ivory and pearl, from Central Asia.

The influence of this can be seen in the funerary figurines – or mingqi – which accompanied the dead when they were buried. Camel figurines were popular but the horse held a special place in Tang society, both because of the importance of the cavalry in expanding and defending the empire, but also because polo was popular with the aristocracy. On this particular example, you can see female polo players on the green discs, which decorate the horse’s harness.

Where to find it: Wing 2, Gallery 5 (The Asian Trade Routes)

6. Sword of Boabdil, the last emir of the Nasrid kingdom of Granada, Toledo, Spain (1475-1525)

Boabdil swords are named after Muhammad XII of Granada, the last Nasrid sovereign of Granada in Iberia (Boabdil is the Spanish name), who was defeated by Isabella of Castile and Ferdinand of Aragon in 1492. The blade, whose solid silver handle is embedded with beautiful coloured cloisonné enamel and gold filigree, is strikingly long, a violent reminder that these artefacts once had real-world purpose. But the real star is the leather scabbard, which is embroidered with intricate silver thread and bears the Nasrid motto, “There is no victor but God”. This sword does what great museum pieces should do – it fires the imagination and makes history seem exciting and accessible.

Where to find it: Wing 2, Gallery 6 (From the Mediterranean to the Atlantic)

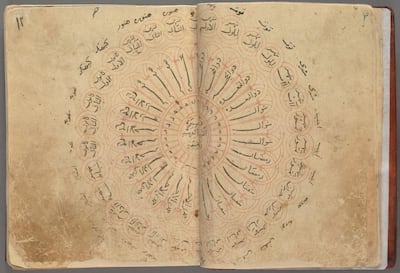

7. Treatise on calendars, a study of astrological calculations, Baghdad, Iraq (c.1200)

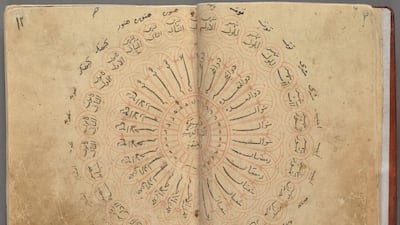

This is a “hidden treasure” in the most literal sense. Ferreted away on the other side of an enormous tapestry, this beautiful, fragile book comprises 79 pages and is divided into two sections: “The Choice of Propitious Moments for All Kinds of Actions” and “Book on the Reliable Way to Read Signs so as to Deduce Unspoken Thoughts”.

Most likely produced for one of the sons of the last Abbasid Caliph in Baghdad, Al-Musta’sim (1213-1258), it is a series of astrological calculations advising on the best moment to undertake a variety of actions, including when to travel by land or sea, when to wage war and even when to take a bath.

The complexity of the content is astonishing, while the faded red and black ink marking the yellowing pages imbues this stunning object with a tangible sense of age.

Where to find it: Wing 2, Gallery 6 (From the Mediterranean to the Atlantic)

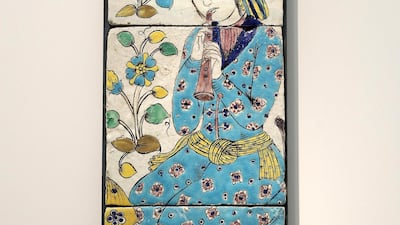

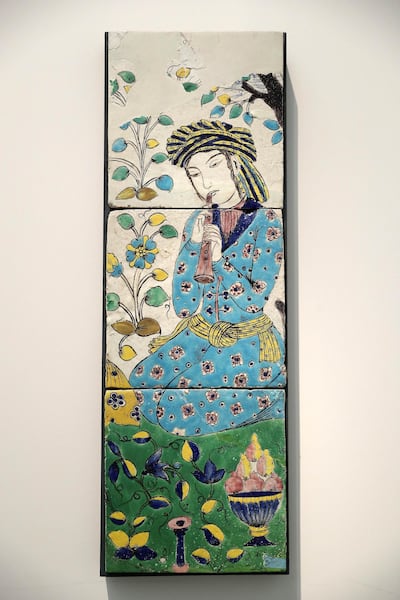

8. Panel with a flute player, Isfahan or Qazvin, Iran (1680-1730)

Perhaps it’s the bowl of pomegranates in the foreground or the exotic yellow and blue plants dancing down the left-hand side but this three-tile ceramic interior decoration has a wonderful feeling of freshness, exuberance and youthful joy.

Scenes such as these were widely used in Iran during the 17th century for the decoration of palaces in Isfahan. I defy you to walk away without a smile on your face.

Where to find it: Wing 3, Gallery 9 (A New Art of Living)

9. Assemblage: Female Nude Sitting in a Pot, Auguste Rodin (1900)

In a small side-room – turn sharply left after van Gogh’s Self-Portrait (1887) – is a small but impressive selection of August Rodin’s sculptures presented alongside works of classical antiquity. Rodin, the guide tells us, “believed that the primary characteristic of classical art was its candour, simplicity and purity with regard to nature, qualities that he himself sought in his own works”.

I am particularly fond of Assemblage: Female Nude Sitting in a Pot (1900). It is a messy, almost clumsy, sculpture. The pot is smeared with plaster and you can see the joins on the woman’s form. And yet, Rodin has still managed to convey so much energy and movement in a few simple shapes. Looking at this small sculpture is like sneaking a glimpse inside Rodin’s studio, spotting a work-in-progress, and understanding something of the method behind the genius.

Where to find it: Wing 4, Gallery 10 (A Modern World?)

10. Untitled Anthropometry, Yves Klein (1960)

It might seem odd to suggest that a painting by Yves Klein, one of the great European post-war artists, is a “hidden treasure”. But in a room where there are works by, among many others, Henri Matisse, Jackson Pollock and Andy Warhol, it would be easy to miss this gorgeous, smudgy wonder.

Untitled Anthropometry is an imprint of the bodies of the artist and his wife painted in International Klein Blue, a pigment created and trademarked by Klein in 1956, which he used to coat the bodies of his subjects before using them as “human paintbrushes”.

This painting is sexuality reduced to its barest form, it is almost like looking at an X and Y chromosome. And yet it is not without feeling. The incomplete outlines of the figures suggest something is missing – two souls left on the canvas by a pair of bodies no longer here.

Where to find it: Wing 4, Gallery 11 (Modernity in Question)

________________

Read more

Louvre Abu Dhabi’s new exhibition: Japanese and French cultures explored side by side

Salvator Mundi: unveiling of world's most expensive painting at Louvre Abu Dhabi delayed

Two of Abu Dhabi's star attractions appear on list of ‘world’s greatest places of 2018’

________________