The visual language developed in Baghdad in the early 1950s did more than just modernise Iraqi art – it established the foundations of artistic identity in the modern age. A new exhibition at NYU Abu Dhabi celebrates that period, when Iraq, newly independent and emerging from colonial rule, was grappling with how to see itself.

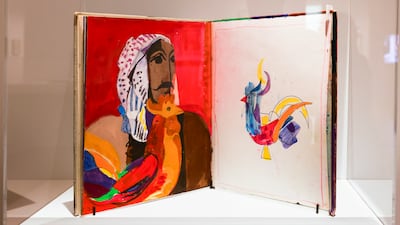

All Manner of Experiments: Legacies of the Baghdad Modern Art Group traces the formation and afterlife of the collective, founded in 1951 by Jewad Selim and Shakir Hassan Al Said. Curated by Iraqi art historian Nada Shabout, the exhibition unfolds across painting, sculpture, works on paper and extensive archival material, much of it rarely seen.

Iraq became a nation-state in 1932. It had a flag, a passport and a repository of antiquities, but no museum of modern art and only a nascent art school. For artists of Selim and Al Said’s generation, the question was not whether to embrace nationhood, but how to give it form. What would a modern Iraqi art scene look like?

The group’s answer lay in a concept they called ilham al turath, which translates to drawing inspiration from heritage.

The NYU Abu Dhabi exhibition demonstrates how radical this proposition was. Rather than treat modernism as a western import to be imitated, the Baghdad Modern Art Group positioned it as a global conversation. They turned to Iraq’s own past – Sumerian sculptures, Abbasid manuscripts, calligraphy and popular visual culture – and reworked these elements into contemporary forms.

Archival documents at the start of the exhibition reveal the intellectual intensity of the project. Posters, manifestos and photographs chart the group’s exhibitions throughout the 1950s, a decade marked by political turbulence but also by optimism in Iraq. Baghdad emerges as a city of debate and ambition, where artists, poets and architects gathered to argue over aesthetics and identity.

At the centre of the exhibition is Selim’s Monument of Freedom, represented through a maquette and contextual materials. Commissioned after the 1958 revolution, it was the first modern public monument in Iraq created by an Iraqi artist. Earlier statues in Baghdad commemorated colonial or monarchical figures. Selim’s frieze instead narrates pre-revolution, revolution and post-revolution through a sequence of sculptural forms that read from right to left, echoing Arabic script. The work draws on Sumerian relief, modernist fragmentation and a distinctly local symbolism.

Selim died before the monument was fully installed, but its impact was immediate and enduring. The exhibition suggests it became both a national emblem and a template for thinking about form. Even today, many young artists in Baghdad know Selim primarily through this work.

If Selim gave the movement a public face, Al Said articulated its philosophical depth. His writings and paintings, several of which are included in the Abu Dhabi exhibition, develop the logic of ilham al turath into abstraction. Influenced by phenomenology, existentialism and Sufism, Al Said later formulated the idea of al bu’d al wahid, or “the one dimension”, shifting attention from representation to contemplation. Surfaces become sites of memory; walls, scars and traces of time carry meaning.

This evolution shaped subsequent generations. Works by artists such as Himat Mohammad Ali and Hanaa Malallah show how ideas of scraping, burning and ruination extend Al Said’s thinking into new material experiments. The sense of continuity is striking, even when styles diverge.

One of the exhibition’s most persuasive threads is its focus on “the line”. Shabout argues that Iraqi art developed a distinct aesthetic mediated through the line, a structural emphasis that connects Sumerian votive figures, the 13th-century illustrations of Yahya Al Wasiti and the abstractions of the 20th century. That lineage becomes visible here. Whether in sculpture, painting or calligraphic abstraction, the line operates as both form and inheritance.

The exhibition also shows that the group was never a rigid collective. Membership was fluid. Artists such as Madiha Umar were already experimenting with the abstraction of Arabic letters before the group formalised its manifesto. Her work, which detached calligraphy into expressive form, laid important groundwork for later developments in hurufiyya. Others, including Dia Al Azzawi, expanded the conversation in the 1960s and beyond, responding to regional upheaval and Arab nationalism while remaining in dialogue with the group’s founding ideas.

Archival material carries particular weight throughout. Given the destruction and dispersal of Iraqi artworks over decades of conflict, documentation often stands in for lost objects. Letters, exhibition catalogues and photographs do more than supplement the works; they become evidence of a fragile cultural record. In this sense, the exhibition doubles as an act of preservation.

The final sections turn to contemporary and diasporic artists. Rand Abdul Jabbar, now based in Abu Dhabi, engages with Iraq through research and inherited memory, reconstructing connections through fragments. Mahmoud Obaidi attempts to revive the spirit of the Baghdad group in later manifestos, seeking renewal under different political circumstances. Across these practices, the influence of ilham al turath remains discernible.

What becomes clear is that the Baghdad Modern Art Group established more than a style. It created a framework within which Iraqi artists could negotiate heritage, modernity and national belonging. That framework had elasticity. It allowed artists to depart from figuration, to embrace abstraction, to experiment with material destruction or conceptual inquiry, yet still articulate something recognisably Iraqi.

There is also a narrative of resilience embedded in the works. Through revolutions, regime changes, war and exile, Iraqi artists have continued to grapple with the same foundational questions first posed in 1951: how to be modern without erasing the past; how to claim heritage without being confined by it?

At a time when global art histories are being reassessed, All Manner of Experiments makes a timely intervention. It positions Baghdad not as a peripheral recipient of modernism, but as a site of intellectual production that reshaped the terms of the conversation. The movement’s experiments, far from concluded, continue to define the contours of Iraqi art today.

All Manner of Experiments: Legacies of the Baghdad Modern Art Group at NYU Abu Dhabi Art Gallery in running until June 7, from Tuesday to Sunday, noon-8pm