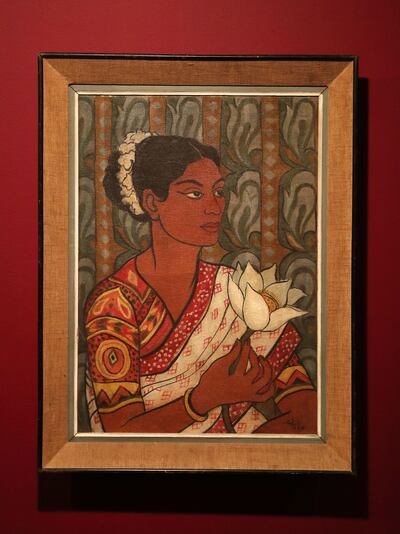

Nazek Hamdi’s The Lotus Girl expresses the enthusiasm of a student who has moved to a new country and become enamoured by its culture. The work was produced in 1955, the same year the Egyptian artist moved to India on an art scholarship.

The painting features a woman in a vibrant sari and floral hairband, the stem of a lotus flower delicately pinched in between her fingers. The wallpaper behind the woman takes obvious cues from the flower, with motifs of tapering petals juxtaposed by the patterns found in batik, a centuries-old wax-resist dyeing technique.

The Lotus Girl, also known as The Lotus Flower, is one of the highlights of a new exhibition at Jehangir Nicholson Art Foundation in Mumbai. Resonant Histories: India and the Arab World is taking place until February 15 and has been organised with Sharjah's Barjeel Art Foundation.

Hamdi’s painting is an example where Indian influences are outwardly evident. The artist studied in India for several years, learning a variety of art forms – from miniature painting to the art of batik – and though she returned to the region as an educator, her time in India gave her work an unmistakable quality.

Hamdi was not the only Arab artist profoundly influenced by Indian traditions. Kuwaiti artist Jafar Islah spent years travelling through India, and cited Indian craftsmen and artists as his informal teachers. Saudi-Kuwaiti artist Munira Al Kazi was born in India, and though she travelled the world, establishing her practice in London and Spain, her formative years in the subcontinent are reflected in some of her artworks.

The influences were bidirectional. Several Indian artists found inspiration in the crafts and aesthetics of the Arab world. One example is Nasreen Mohamedi, whose sense of abstraction was strongly influenced by the deserts of Arabia. Her family travelled frequently between India and Bahrain, where her father moved in 1912 to establish a photography business.

As such, the modern art histories of India and the Arab world are intertwined. The exhibition at the Jehangir Foundation spotlights several crossing points, while also delving into parallel developments in figurative and abstract painting.

“We’re trying to relook at histories from a different perspective,” says Puja Vaish, director of the foundation and co-curator of the exhibition. “We want to look at the connections between south and south, east and east, rather than just east and west.”

Co-curator and director of Barjeel Art Foundation Suheyla Takesh adds: “A lot of these artists were either friends or maybe studied at the same universities. They were trained in the same curricula or even trained by the same people. A lot of them also had points of interest, intersections abroad, not necessarily a direct link of travelling to India or to the Arab world, but in studios in Paris or London.”

Nevertheless, one important intersection was the Triennale India, an event that famed art critic John Berger described as “escaping from or even overthrowing the hegemony of Europe and North America”.

Right from its inaugural event in 1968, the triennale sought to reposition India within a global art discourse, beyond centres in the West. “The idea was, as an independent country, to make its mark on a global art stage,” says Vaish. “And to include not only artists from America and Europe, but also from countries of Africa, the Middle East and other Asian countries.”

Several Arab artists who feature in Resonant Histories have participated in the early iterations of the Triennale India, with their works placed in direct dialogue with Indian modernists. Yet, the broader implications of these connections were not fully considered at the time.

“The conversations that happened within India focused more on the bureaucracy within the academy, which started the triennale, and the selection of Indian artists,” Vaish says. “At that time, it didn't grasp the real potential.”

Resonant Histories returns to these overlooked moments, charting a wider network of artistic practices and parallel experimentation. The exhibition does this across seven thematic sections.

“These are not rigid sections,” Vaish says. “Many works could also fit in somewhere else, but the sections just give the exhibition a guiding theme.”

For instance, one section, Visions of Freedom, brings together artists responding to anti-colonial struggles, liberation movements and the project of nation-building. Political figures such as Mahatma Gandhi became shared subjects, appearing in the work of Indian artists such as Akbar Padamsee, as well as Arab artists, including Egyptian painter Ali Hassan, who depicted Gandhi only a week after his assassination.

Then there are scenes of social movements. In Nation and Leader (1962), Syrian painter Said Tahsin depicted Gamal Abdel Nasser, laurel branch in hand, marching confidently forward as a symbol of Arab unity amid cheering crowds, as well as images of war and resistance. Nilima Sheikh’s My Hometown (2009) also contains similar scenes, with images of suffering as well as longing, reflecting upon the dualities of Kashmir as both a scene of strife and an idealised landscape.

Palestine also features heavily in this section. Kuwaiti artist Sami Mohammed’s bronze sculpture Statue of Sabra and Shatila (1982) depicts with visceral effect the massacre in the Palestinian refugee camps the piece is named after. Syrian artist Naim Ismail’s Al Fiddaiyoun (Freedom Fighters) from 1969 also has strong references to Palestinian identity, particularly with the inclusion of keffiyehs within the composition. But it is The Life (Waiting) by Emirati artist Abdul Qader Al Rais – painted in the late 1960s and depicting four Palestinian refugees in Kuwait after the 1967 Naksa – that has a particularly interesting connection to India.

“That work was actually shown at the first edition of Triennale India in 1968,” Takesh says.

Another major section explores parallel in abstraction. Works by Seta Manoukian, Ghulam Rasool Santosh, Al Kazi, Sayed Haider Raza, Hashim Samarchi and Nasreen Mohamedi each show individual takes on what abstraction could be. There are works derived from geometric explorations as well as scripts, ancient languages and computer graphics.

“Abstraction was one of those areas that was on both our minds as we were working,” Takesh says. “And, really, the genealogical lines of these movements are multiple and very diverse.”

Resonant Histories is rich with these echoes. Yet, rather than claiming itself as a comprehensive study of the connections between Indian and Arab modern art, it is positioned as a starting point, bringing conversations that may have been overlooked in their time to the fore.