The second half of the 20th century was a time of dramatic shifts for the UAE and its neighbours. But amid fields of rapid socioeconomic and cultural change, one particular seed blossomed relatively unnoticed — a tradition of modern arts. Until now.

On Tuesday, after years of planning and curation, NYUAD Art Gallery will launch Khaleej Modern: Pioneers and Collectives in the Arabian Peninsula — a landmark exhibition exploring the rise of contemporary art in the UAE, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Bahrain, Qatar and Oman.

“It’s not actually timely,” the exhibition’s curator, the art historian Dr Aisha Stoby tells The National. “It’s surprising to me that it hasn’t been done yet.”

Stoby, who curated Oman’s first pavilion at the Venice Biennale, says she is grateful for having had the time to investigate the subject in such depth.

“Looking at early exhibition spaces, artist-run spaces and curatorial projects, from a very early stage, I was aware that there was not necessarily a scarcity of information, but a sparsity of information.”

What emerged from her painstaking research was a clearer picture of how, after the discovery of oil, the forces of urbanisation, globalisation and other factors combined to propel the region’s nascent visual arts movements.

As foreign workers and teachers poured into the peninsula, and those from the region studied abroad, new conversations and understandings arose around the ideas of public and private spaces and their relationship with national identity, as expressed through art practices.

Stoby says the exhibition, which covers an “extraordinary period" spanning the 1940s to the late 2000s, represents a point of transition, a continued conversation between tradition and modernity. One of the key questions the exhibition raises is: What does it mean to be "modern"?

“I want us to try and rethink what our traditional understanding of ‘modernism’ is within this show, and try and unpick some of the things that may even be stuck in our minds; our associations with those words from a European context,” says Stoby.

“Modernism can be applied even as far back as the Islamic Golden Age — you see industrialisation, you see the thought that comes as a result of that and, by extension of that, an incorporation of the visual and poetic arts.”

Some of the dozens of pieces in the exhibition will be on view for the first time in decades, enhanced with the addition of rare and archival material. Stoby hopes the project will not only offer the region an opportunity to re-evaluate its own history, but contribute to wider understandings of modern visual art, geared towards a more nuanced and inclusive appreciation of global art histories.

The foundation

Although the UAE is today home to countless galleries and museums, including the prestigious Louvre Abu Dhabi, there was a time where for the region's earliest modern artists, the craft itself was just the beginning. They had to not only produce their art, but contextualise it through the creation of spaces, galleries, communities and even audiences.

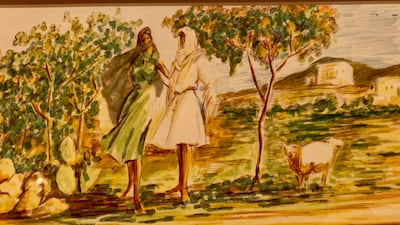

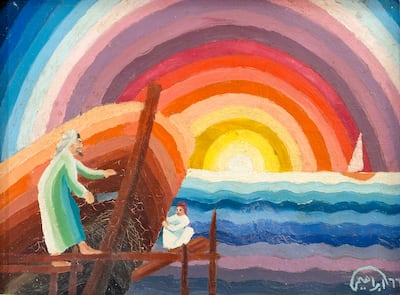

One of the earliest artists, Stoby highlights, who began to bridge these various influences was Mojib Al Dosari, who painted the exhibition’s oldest painting and died in 1956 in his mid-thirties. Al Dosari was a true pioneer, who held his first show in the early 1940s, before going on to study in London and Egypt.

“He passed away very young, quite tragically. He had a stomach condition.” In his final days, Al Dosari was said to have lamented, "I wish I could take my blood and paint with it."

Stoby says it is a beautiful sentiment. “It speaks to this idea of a real desire to create that’s beyond the time, and beyond the infrastructure. It’s very visceral.”

Pioneers such as Al Dosari are viewed not just as artists, but as builders. For them, mastering their crafts and creating their art was just the beginning; from there they had to build the very foundations of a modern art movement.

“We’re looking at these figures as establishers; the infrastructure that came alongside it and the increasing global understanding of audiences that emerged alongside this as well.”

Early pioneers

Khaleej Modern is separated into four broad sections, with an organic narrative that simultaneously travels thematically, chronologically and geographically. The first looks at early Kuwaiti pioneers, focused on Al Dosari and Khalifa Al Qattan, who held exhibitions at the Mubarakiya School, in 1943 and 1953 respectively.

“The early pioneer section is about what it truly means to be building your own audiences and what it means to be not just an artist, but a founder and an establisher.”

One of the key works included in the very first room of the exhibition is a piece by Munira Al Kazi, called Mother and Child, from circa 1960. “She’s an astonishing artist," says Stoby.

The Saudi-Kuwaiti artist was born in India and studied at London’s Central Saint Martins, before going on to have her works collected by both Victoria & Albert and New York’s Museum of Modern Art. Aside from running a studio in Ibiza, she took part in the inaugural exhibition at Kuwait’s Sultan Gallery in 1969, alongside Iraqi artist, Issam El Said.

Including her work in the first room impresses upon visitors the “cosmopolitanism and openness that was perhaps not uniform everywhere, but present within artistic communities”, says Stoby.

“Similarly, we have a work by Ibrahim Ismail, which depicts the practice of portraiture and studio painting on figures — in which he’s in his atelier painting a model, in front of him. So we’re seeing evident within these works these very early practices.”

Meanwhile, Khaleej Modern represents the dawn of Saudi’s modern art community with Mohammed Rasim, who was born in 1911, studied in Turkey and held his first exhibition in Jeddah in the early 1950s.

Landscapes

“The second section looks at landscape, not just in terms of landscape painting as both preservation and documentation, but in development of the landscape itself — in building, development, urbanisation. It looks at the period following the discovery and culmination of oil, and how that affected the landscape,” says Stoby.

Although Khaleej Modern begins with the discovery of oil, Stoby believes that the prosperity that came from this was not the impetus for modern art movements, but a catalyst for them.

She says it built on a pre-existing “material culture and poetic culture that was very rich and prevalent throughout the region”, with an “increasingly global understanding of what it means to work within the visual arts”.

This second section is centred on a group of artists from Bahrain sometimes referred to as the Manama Group, who were known for working intensely with landscape practices. “These are some of the artists that went on to found our creative infrastructures.

“Those artists went on to found the Bahrain Arts Association in 1970; each of the artists that were displaying not only had very prolific art practices, but they were founders; they were gallerists; they were mentors; they were teachers.”

New communities

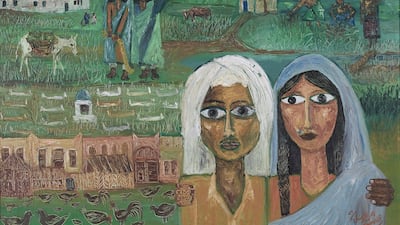

The third section, titled Self-Representation and Portraiture, explores the distinction between private and public space, and the simmering tensions between tradition and modernity that emerged during the mid-20th century.

“From the mid-60s onwards, you have many of the first very important exhibitions that were taking place at both of these fine art centres and these artists and their work reflect that.” After the Manama Group was formed, similar collectives emerged in Saudi Arabia, the UAE and Qatar.

While some were more formal than others, unlike most modern art "collectives", the Arabian Peninsula’s tended to emphasise the individuality of their members.

Established by artist, Mohammed Al Saleem in 1979, the Saudi House of Fine Arts was not only a public gallery, but an important meeting centre and space, in which artists were given lessons and free art supplies. It represented the power of community in the nascent modern art movements.

The next year, in Qatar, Yousef Ahmed, Hassan Al Mulla and Muhammad Ali Abdullah, known as the Three Friends, formed the Art Society in 1980, through which a whole generation of artists passed.

Building an audience

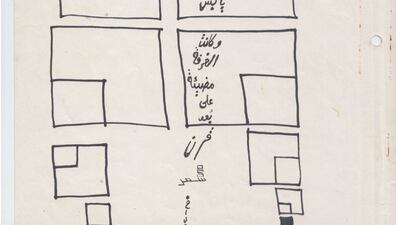

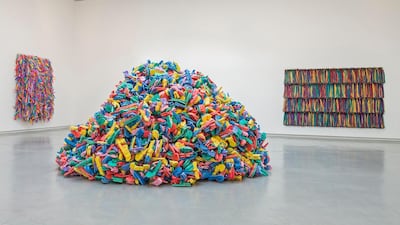

The final section, looks at collectives in the UAE and Oman. One of the key figures, Hassan Sharif, was a remarkably creative pioneer in the Emirati visual arts landscape. Having studied in London and co-founded the Emirates Fine Arts Society in 1980, he produced a series of experimental exhibitions, including the One Day Exhibition in 1984.

The show was seen by four other artists, Khalid Albudoor, Nujoom Alghanem, and Yousef Khalil, who together formed a collective known as the Aqwas "Arches" Collective, named after Sharif’s arch-shaped creations. They distributed a journal, each with a piece of chewing gum, to newspapers and other artists. Sharif later formed "The Five", with his brother Hussain, Mohammed Kazem, Mohamed Ahmed Ibrahim, and Abdullah Al Saadi.

The Conceptual Turn space “presents a proposition of modernism as a very globally nuanced and ongoing theme because these are not mediums that you would typically associate with the modern”.

Reflecting on the UAE’s art scene of the 1980s, the great Emirati pioneering artist, Sharif, who died in 2016, once remarked: “I didn’t only make art, but I made my audience too.” He added: “I had to contextualise what I was doing.”

Stoby says: “These are artists who were not just important for their techniques or for their prolific and dynamic art practices, but more than that, were establishers and pioneers within their countries.” She describes them as “anchors”, adding “that quote by Hassan Sharif is not on its own”.

Hassan Meer, a pioneering Omani artist who was active from the early 1990s onwards in video art and installation work said something similar. Like other artists who studied abroad, when he returned, he wanted to bring back not only his practice, but “to go beyond”, to cultivate. Having introduced new media art into Muscat’s art ecosystem, Meer established a community of creatives in Oman; centred around The Circle, which he formed with Anwar Sonya and Saleem Sakhi.

“I think there’s an aspect of giving back; so, mentorship, teaching, wanting to create a progression and a history, and for me I think that is something really remarkable and worth commending.”

Stoby also pays tribute to the influx of teachers from the greater Middle East who came to establish the early art programmes in schools that preceded the modern movements.

“We see a lot of Egyptian, Syrian and Palestinian influences evident within our works, and various methods and styles that are present within the work.

“I think until today, as we’re continuing to establish our higher art educations, this moment of research, of travel, whether you’re in the West or in the Middle East, is something that is important to gain greater awareness of art movements generally, in a very broad sense.”

NYUAD Art Gallery executive director and university chief curator Maya Allison refers to Khaleeji Modern as a “crucial” and “pathbreaking” project. She adds: “An exhibition like this is quite rare, a kind of opening salvo and call to action, offering new vistas on art history and art practice in this region.

“Rather than a definitive survey, this project sets us on a journey to explore the under-studied — and, for some people, unknown — emergence of modern art in the Arabian Peninsula over the last century.”

Reflecting on the exhibition, Stoby says it has been a “labour of love”. And while it may be long overdue, looking forwards, she says: “We like to think of it as the start of an ongoing project.”

Khaleej Modern runs from tomorrow until December 11 at NYUAD Art Gallery. More information is at www.nyuad-artgallery.org

Scroll through more images of Hassan Sharif's work below: