Saudi artist Muhannad Shono’s latest installation as part of the inaugural Islamic Arts Biennale in Jeddah is an exploration of the relationships between light and dark, softness and harshness, the tangible and the intangible, the individual and the collective.

Launched earlier this week, the biennale presents Shono’s work alongside several contemporary commissions and rare Islamic relics — together exploring a sense of spiritual belonging beneath the theme of Awwal Bait, or First House.

Standing beside his installation, Letters in Light, Lines We Write, the artist explains his approach to The National: “How do we read what the spiritual is? Is it a hard edge? Or is it something with a lot of forgiving space, where the light is soft?"

The work is a reminder of the importance of humility; that in the face of collective rigidity, sometimes individuals must be willing to “circle back into the darkness to find the light again; a light that is more nuanced, softer on the edges, more shadow and light, rather than day and night”.

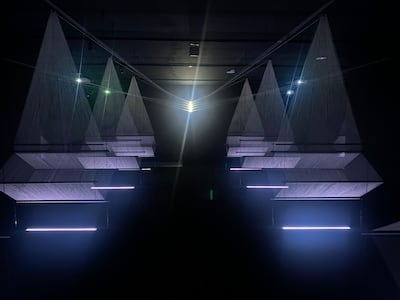

Separated into two darkened rooms, the work first presents a singular source of light, shimmering through a tent-like form, composed of innumerous thin threads.

Set to a soundtrack of vocal chants by Somali singer FaceSoul, who lives in London, the structure hovers overhead — creating a hypnotic effect; as waves of light ripple through the darkness, before fading again to black. Knots are carefully placed along the intricate structure, an act of delicate devotion that lends a touch of slack to the lines; giving them room to bend and flow.

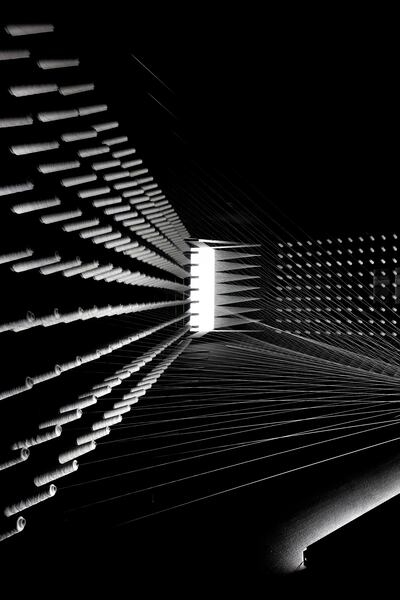

In the second room, light emanates from a singular point outward in straight lines, materialising downwards into complex geometric structures. Angular, they evoke a sense of repetition and ritual, where the softness of the light is filtered through a broader matrix of rigidity, mirroring the relationship between the personal and the societal; the self and the system. It presents a network of figures operating within an almost mechanised congregation, where the light takes very defined and static forms.

Shono’s work is multidisciplinary, with many layers of depth adding an unexpected yet vital dimension to the biennale. The project calls to mind his work at last year’s Noor Riyadh — where he presented I See You Brightest in the Dark; a sweeping intervention spanning several rooms and floors in a 1980s building in Riyadh’s Al Malaz district. It had illuminated threads climbing from the basement to the roof, morphing along the way to construct a narrative of loss, devotion and surrender.

Both works follow a bold trajectory of work in which the artist has mirrored Saudi Arabia’s rapid social change. Last year, this culminated in him representing his country at the Venice Biennale with his installation The Teaching Tree.

Curated by Reem Fadda, director of Abu Dhabi’s Cultural Foundation, The Teaching Tree presented a colossal sculptural form embodying resilience, regeneration and rebirth. Starting with a singular stalk, it ballooned into a great mass of refuse palm fronds, painted black and bursting through the 40-metre rectangular pavilion.

A pneumatic function allowed the piece to breathe and move; giving it a generative and lifelike quality. It built on Shono’s fixation on “the line” — a concept that goes back to his upbringing in Saudi Arabia at a time of heightened conservatism, when black lines were often used to redact and censor.

Fittingly, the launch of the multidisciplinary artist's Islamic Arts Biennale installation coincided with the release of his The Teaching Tree catalogue. To mark the occasion, he and Fadda held the last in a series of talks on the work.

It was an emotional end to a project Fadda describes as simultaneously “historic” and a “catalyst”. She adds: “I feel that's something that will become a reference point for Saudi, and for the art scene in general.”

Shono describes The Teaching Tree as “an act of creative resistance” and “a true embodiment of the collective spirit”. He adds: “It is the child me, who was told not to imagine, who was asked to take the line and strike it through the neck of characters that I was manifesting as a child, and I took that line, and I wanted to wield it to create.”

Like the line, the colour black is also a creative response to censorship — from a time when Shono says black ink was used to “obscure the word, the text, the image and the meaning”. He adds: “For me, it did not hamper my understanding. It's hyper-accelerated my imagination, because I had to imagine infinite possibilities of what that void was meant to hold. And it was a reclaiming of the line which was used to decapitate the figure.”

Shono says representing The Teaching Tree was also personally satisfying as a naturalised Saudi citizen who is the son of Syrian immigrants.

“I never thought that I could represent Saudi Arabia. My family name, Shono, is not traditional — growing up in Riyadh, you're often very much reminded that you are not originally Saudi.

“For me to find myself in this position where I'm able to represent my country in the National Pavilion was so telling about how we're changing as people here, and this kind of expanding acceptance. So it was definitely an honour and very emotional.”

He adds: “And it is not just my story, it is a journey, it's a story of a collective spirit, that has resisted this act of limiting the imagination, and allowed for things to grow — a single line grows into another, and multiplies.”

For his part, the artist is passing it forwards through collaborations, and his own studio — through which he uplifts emerging artists. Shono says he wants to share his platform to help younger artists find a way to express themselves, and be heard.

“There’s a collective coming together because there is a collective hope for this kind of work to take place. So the studio is currently a place for me, but also a place for people who are working with me on projects, to also have space to manifest their own work and meet people who are coming through.

“Within the mind, you can actually reshape the world around us. And if you can build it within the mind, and if you can see it, then it can take shape. I really think that is something that we experienced here, and we are [still] experiencing here.

“Once this individual change happened within each person's mind here, this country began to change, walls began to fall, and people have changed.”

The Islamic Arts Biennale runs at Jeddah’s Western Hajj Terminal until April 23

Scroll through more images from the Islamic Arts Biennale below