Like many things in the Levant, even food is political – from culinary traditions preserved across time and borders in defiance of colonial erasure, to the social importance of sharing comforting meals regardless of the crisis at hand.

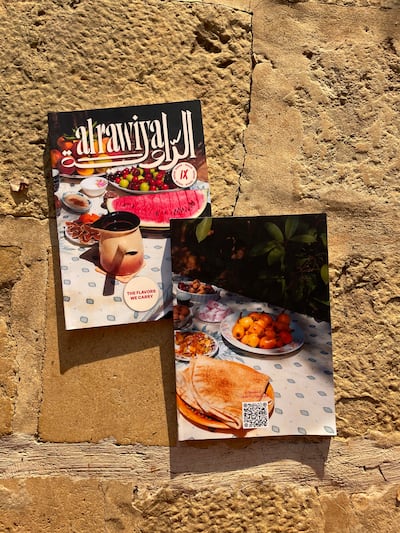

Al Rawiya has documented untold stories from Lebanon, Syria, Jordan and Palestine for the past five years. Now the independent women-led platform has published its first print edition, turning the focus to food traditions, flavours that extend far beyond sustenance and the cultural impact of cuisine.

Titled The Flavors We Carry, the inaugural print compendium brings together stories by Levantine writers, artists and creative practitioners in both Arabic and English, offering personal reflections on food and its role in shaping the region’s social and political fabric.

“From the start, we wanted to speak about topics in ways that are accessible, and to break the status quo by addressing subjects that traditional media often overlooks,” Al Rawiya founder Stephani Moukhaiber tells The National. “We focused on refugees, migrant workers, women and the diaspora. Many of our topics touch on politics, social justice, human rights, culture and art.

“Five years later, we’re still doing that – independently and self-funded – but we want to expand, and having a physical edition is part of that,” she adds. “It’s a way to archive our history, our traditions and our culture in a form that speaks to our generation. Publishing in both Arabic and English is also essential.”

The volume explores historical recipes and culinary rituals as markers of memory, identity and belonging, examining how certain foods offer comfort during grief and upheaval, and how cuisine can become an act of resistance in the face of occupation.

It also seeks to bridge the distance between the Levantine diaspora and their homelands, acknowledging the bittersweet relationship many maintain with their heritage. Set against food insecurity, systemic displacement and cultural erasure, the stories span projects such as Paris-based Lebanese artist Sama Beydoun’s Mother Tongue series, which invited members of Lebanon's diaspora to teach her inherited recipes, documenting intimate exchanges in the kitchens of strangers.

Jordanian writer and composer Dina Tahamouqa, meanwhile, reflects on how Circassian communities have preserved – and adapted – their culinary traditions in exile, creating a distinct subgenre of Circassian cuisine shaped by Jordanian influences.

“Al Rawiya means 'the storyteller’, so it was important that all the contributions were personal,” Moukhaiber says. “The writers share their own experiences to make the work as relatable as possible. Several pieces explore the idea of the luxury of time – particularly in Lebanon and Palestine – where conflict and war mean we often don’t have the time to learn what our land offers, or how to care for it.

“For example, Mexican-Palestinian academic NA Mansour writes about having the luxury of time in Mexico to learn how to cook cactus fruit, known as nopales there and soubber in Palestine,” she adds. “In Mexico it’s part of everyday cooking, while many people in Palestine – especially in Gaza – have never had the opportunity or knowledge to prepare it and access its nutritional value.”

One of the most powerful chapters examines Israel’s attempts to erase Palestinian cultural practices by outlawing the foraging of sage, mallow and thyme – wild herbs that have grown abundantly and been gathered by locals for centuries. The piece is written by Palestinian architect and animator Ghayad El-Khatib.

Framed as environmental protection measures, the laws were introduced to sever the intimate, generational relationship between Palestinian women and the landscapes they sustain. El-Khatib weaves research with personal memory, recalling lessons in foraging passed down by her grandmother.

“It meticulously traces the deliberate criminalisation of this botanical heritage,” El-Khatib tells The National. “Za'atar was listed as a protected plant following the Tel al-Zaatar massacre in 1976; mirmiyya or sage was targeted by agricultural policies designed to favour settler economies; and khubeizah or mallow, a wild edible synonymous with ancestral resilience, was rhetorically reframed as a threat to the state’s ecological order.”

She adds: “Every winter, for as long as I can remember, this ritual has defined my life. I go out to collect plants, especially khubeizah, from the slopes of Mount Carmel or from the earth near my house. But the ritual began in the fields of Safuriya. We could not go to our ancestral village, Al-Mujaydil – it was erased. Safuriya, with its open land, became the closest place that still felt like home.”

The chapter recounts stories of women being arrested or fined for foraging, drawing testimonies from across Galilee and the West Bank. Combined with an examination of the legislation and the Green Patrol – a military unit tasked with preventing Palestinians from foraging or cultivating endemic plants – the piece foregrounds the quiet resistance of women who continued to practise their food rituals in defiance of the law.

To accompany the launch, Al Rawiya is planning a series of community events across Lebanon and Amman, as well as diaspora cities including London, Paris and Montreal. Like the launch at Souk Al Tayeb in Beirut, the gatherings will feature food workshops and tastings, performances, storytelling sessions and multisensory tables where participants can see, touch and smell the ingredients referenced in the stories.

Moukhaiber says the print edition will be published annually with a new theme each year, alongside the digital platform, with ambitions to expand further and print more frequently in the future.