The rapid development of Uzbekistan’s art sector offers a case study in how countries can mine their history to forge a modern cultural economy.

The country is drawing on its Silk Road and Islamic legacies to bolster cross-cultural connections that extend to the Arab world, while also building the infrastructure necessary for a new creative generation to flourish.

Driving this change is the Art and Culture Development Foundation (ACDF). Since its establishment in 2017, the government-backed body has launched several initiatives, revived historic sites and effectively positioned the country within regional and global networks.

Centre for Contemporary Arts Tashkent

The impact of these new projects have already begun to materialise. One of the earliest and most visible projects is the Centre for Contemporary Arts Tashkent (CCA). The centre is housed in an industrial building – a diesel station and tram depot that was originally built in 1912 – that has been revamped by the French-based architecture firm Studio KO.

As its name suggests, the centre is dedicated to contemporary art, but also fosters research and community-building. The latter aspects of its mission is clear when considering the venue’s location.

“We realised that we would like the place for the younger generation to gather,” says Gayane Umerova, chairperson of the ACDF. “This is why we decided to have the centre in the student neighbourhood, between three universities, to create not just an art community, but a social and cultural one. People can engage with different disciplines.”

The venue will officially open to the public in March. It will contain exhibition spaces, some of which extend underground, as well as a library.

Details of its inaugural exhibition were recently revealed. Hikmah, Uzbek for wisdom, will take place when it opens next year. It will bring together works by local and international artists, including several familiar names in the Arab world.

Highlights include Flying Carpets, a work by Tunis-born artist Nadia Kaabi-Linke that is on loan from the Solomon R Guggenheim Foundation; a new commission by Saudi artist Muhannad Shono; Archive of Mind, a participatory installation by South Korean conceptual artist Kimsooja; sculptural work by Lebanese artist and filmmaker Ali Cherri; and a new installation by Shokhrukh Rakhimov, a seventh-generation Uzbek ceramicist.

Even though the centre is months away from its opening, various strategies have already begun taking shape under its banner. The residency programme is the centrepiece.

The CCA Residences is located in a satellite venue in Namuna, in a site that was once a madrassa – an Islamic school – and which has also been redeveloped by Studio KO.

With its brick construction, arched walls and carved wooden ceilings, the structure takes several noticeable cues from Uzbekistan’s architectural past, merging gracefully with the historic elements of Namuna. The CCA Residences serve as a key space for artists to develop their craft across an eight-week programme, while also taking part in public events, including workshops and talks.

Last year, in the programme’s inaugural run, the centre hosted a mix of Uzbek and international artists, including Shono and Dutch-Moroccan designer Mohamed Benchellal. This year’s cohort, meanwhile, includes British-Egyptian sound artist Sami El-Enany, British-Iranian fashion designer Paria Farzaneh, art historian Vivek Gupta, Afghan miniature painter Jamila Sadat and Uzbek artist Dishon Yuldash.

“The CCA’s inaugural programme reflects a commitment to curating across geographies, generations and disciplines, bringing together pioneering voices from Uzbekistan, Central Asia and beyond,” said Sara Raza, artistic director and chief curator of the CCA.

“The programme is rooted in critical inquiry, cultural resonance and collective imagination. At its heart, the centre is a space for dialogue: between artists and audiences, local histories and global ideas, where the past becomes a catalyst for future possibilities.”

The National Museum of Uzbekistan

Alongside the CCA, the government is also investing in the National Museum of Uzbekistan, putting forth a project of unprecedented scale.

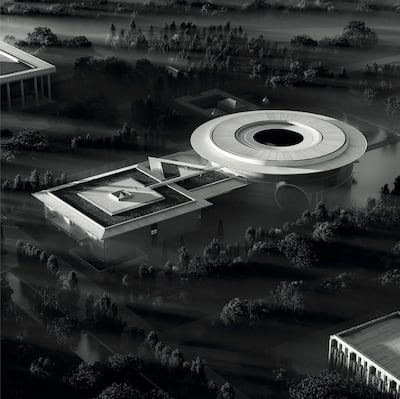

The museum is designed by Tadao Ando and marks the famed Japanese architect’s first project in Central Asia. It is slated for a 2028 completion.

Located at the heart of Tashkent, the museum is designed with the minimalist approach Ando is known for, with circles and squares adjoined by triangles, while also being informed by traditional Uzbek design elements.

The museum will include masterpieces from the national collection, as well as acquired works that reflect on the country’s evolving identity and its global ties.

“It’s vast,” Umerova says. “It’s about the capacity building, because we have a huge young population. It's about mentorship.”

Alongside exhibition spaces, the museum will have several dedicated facilities for restoration and preservation. It will also have a restaurant, which is a novel addition for any museum in Uzbekistan.

“This is not what we usually have here. We respect art and you eat in another place,” Umerova says. “We're trying to combine it, because it's all about the social exchanges. We are competing with the mall. We are competing with the cinema because we want people to be engaged more in these places. We want people to spend time there.”

The museum is already gearing up for international collaborations, well before its opening. Many of these are deeply rooted in the Arabian Gulf.

Umerova notes continuing collaborations with Louvre Abu Dhabi and Guggenheim Abu Dhabi, as well as with institutions in Qatar such as the Museum of Islamic Art, the National Museum and the upcoming Lusail Museum. She adds that Saudi Arabia has also contributed, bringing its Al Musalla project to the Bukhara Biennial.

“We engage with Islamic biennial every two years, hopefully with the contemporary art, once we feel mature enough to show contemporary work outside,” Umerova says. “We really established good partnerships around the region. We were bringing back these Islamic roots and this brotherhood in the region.”

Bukhara Biennial

The Bukhara Biennial is one of ACDF’s most symbolic projects. Set in a city long associated with the Silk Road exchange, the biennial aims to position Bukhara not only as a historic site but as an active cultural platform for both local audiences and international visitors.

“This is exactly why we decided to do this biennial in Bukhara,” Umerova says. “Because it was a melting pot. And it was a place where people would meet, trade, exchange culture and cuisine. We want to build on our legacy from the Silk Road.”

Curated by Diana Campbell, the biennial will connect traditional craftsmanship with contemporary art, ensuring that the event reflects both heritage and new creative directions. “By investing in traditional art we're trying to engage in more contemporary art, and inspire this younger generation of artists to think creatively, in a contemporary kind of world, but also respecting traditional artisanship,” Umerova says.

Umerova says the biennial is a prime example of how the foundation is seeking to work with local communities to bolster the creative economy.

She adds that the project has been shaped with community input from the start, with young people in Bukhara set to act as mediators during the biennial and local artists, artisans and restaurants all playing a role.

“We always talk about the legacy brought here by Al-Khwarizmi, Ibn Sina, and so on, but what are we doing today? We have to build this legacy today together.”