Look under old mattresses, put your hands down the sides of second-hand sofas or lift up floorboards in homes across the eurozone and you may still find old coins and notes denominated in long defunct national currencies.

That is because in some eurozone countries, including Germany, it is still possible to exchange unlimited amounts of old currency into euros – 20 years after the notes and coins were first adopted by 12 countries on January 1, 2002.

In Berlin, the capital of Germany, and the neighbouring state of Brandenburg alone, about 2.63 million deutschmarks, the equivalent of €1.35 million were exchanged between January and the end of November 2021.

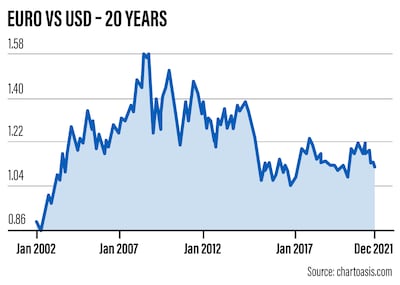

Today, the euro, which has dropped 7.27 per cent this year against the dollar as investors bet the European Central Bank would be slower to end pandemic-era stimuluses than rival central banks, is the currency for more than 340 million people in 19 EU member states, according to the ECB.

Meanwhile, 60 countries and territories outside the euro area, representing 175 million people, have linked their own currencies to the euro, either directly or indirectly.

As a result the euro is the world’s second currency for international payments, borrowing, lending and central bank reserves, with more than half of global green bond issuance denominated by the euro.

Despite this, older currencies can still be found, with about 12.35 billion deutschmarks (€6.31 billion) out there somewhere, according to the Bundesbank, some in the hands of collectors.

How the euro took on the mighty US dollar

The euro has come a long way since it first went into circulation two decades ago when French president Jacques Chirac hailed the launch by declaring that Europe was "affirming its identity and its power".

To the euro's biggest fans, the currency was not only a leap of faith into European unity, but also set up a rivalry with the US and its powerful dollar.

Twenty years on, there is no question that the dollar still reigns supreme, with the spread of coronavirus causing the dollar's value to jump as investors poured into the safety of the world's de facto global currency.

While about 60 per cent of foreign-exchange reserves parked in central banks are denominated in dollars, the euro's share makes up just 20 per cent, according to the European Central Bank.

But even if it poses no direct threat to the mighty greenback, Europe's single currency has kept up the momentum since it began circulating in January 2002, becoming a respected runner-up to the US dollar.

ECB President Christine Lagarde, who shares her birthday with the currency on Saturday, is naturally a big fan, stating that the currency has helped to unite Europeans, citing a Eurobarometer survey that found 41 per cent of citizens consider the single currency second only to freedom of movement.

The currency also has a 78 per cent approval rate among citizens – with not even a flicker of doubt in the year the eurozone finally parted ways from the UK following the conclusion of Brexit.

Recalling her early fondness for the euro in a newspaper column, Ms Lagarde said she spent January 1, 2002 with family and friends at her home in Normandy, heading to a cash machine shortly before midnight “anxious” to withdraw her first euro notes.

Despite her friends believing the system would not cope and would dispense French francs as it became overwhelmed by demand, the machine delivered the crisp euro notes she desired.

“That personal moment was one small part of the world’s largest ever monetary changeover, and the euro has only grown since,” she wrote in the Irish Independent on Friday.

Euro first dates back to 1999

The origins of the euro actually date back a little earlier, to 1999, when 11 countries, including France, Germany, Ireland and Spain, fixed their exchange rates and created a new currency with monetary policy passed to the ECB.

However, it was more of an invisible currency in those early years, used only for accounting purposes and electronic payments, before euro notes and coins went into circulation at the start of 2002 with the addition of Greece.

While Ms Lagarde joined the many New Year’s Eve revellers queueing at cashpoints to withdraw notes, it was not an entirely smooth ride with the switch provoking sporadic price increases across Europe.

From Spanish bus tickets, which jumped by 33 per cent, to a Finnish bazaar, where "everything for 10 markka (€1.68 euros)" was now "everything for €2", many price tags were a little heavier once the single currency became legal tender.

Wim Duisenberg, the ECB president at the time, warned shopkeepers not to take advantage of the euro launch by increasing prices, although he said that he had not seen signs of widespread abuse.

"When I bought a Big Mac and a strawberry milkshake this week it cost €4.45, which is exactly the same amount as I paid for the same meal last week," Mr Duisenberg said.

Meanwhile, France urged citizens to not rush all at once to the banks with their savings, often hoarded under mattresses and in jam jars, because they had until June 30, 2002 to get rid of their francs at commercial banks and until 2012 at the Bank of France.

Along with Germany, Austria, Ireland and the three Baltic states also still allow residents to exchange their old currencies as well, while Italy stopped redeeming its old coins and banknotes in 2011, with Greece following suit in 2012.

The rise and fall of the currency

The first 10 years of the euro were about the currency’s establishment and growth, with eight more countries joining the club, including Cyprus, Estonia, Malta and Slovakia.

But the second decade was consumed by the fall-out from the global financial crisis with speculation the currency union would break up amid soaring bank debt between 2011 and 2015.

European Central Bank head Mario Draghi helped end the market turbulence with his promise in July 2012 to “do whatever it takes” to preserve the euro.

The ECB later offered to purchase the government debt of countries facing excessive borrowing costs, when Spain, Portugal, Cyprus and Greece had to seek help amid a sovereign debt crisis following the credit crunch.

Emergency measures were put in place, including the creation of the European Stability Mechanism, a financial body that helps countries in the economic bloc in distress.

Omicron offers new challenge on eve of 20-year anniversary

While the 20-year anniversary may be slightly mired by the surge in Covid cases as the Omicron variant sweeps across the continent, the ECB is celebrating with a light display in blue and yellow, the colours of the EU, projected on its skyscraper headquarters in Frankfurt, Germany.

Ms Lagarde said in a video message that “the euros have become a beacon of stability and solidity around the world, thanks to you, the hundreds of millions of Europeans who trust it, gave it strength, confidence, and transact with it every day”.

The latest challenge for the currency is the pandemic, with the ECB setting up a €1.85 trillion bond purchase programme to keep borrowing costs down for companies to help them through the worst of the pandemic.

ECB

In her New Year's Eve column, Ms Lagarde wrote that the single currency had made the economic bloc more resilient and better equipped to handle crises.

"The recent economic shocks would have been even more serious if it hadn't been for the stability and integration the euro brought to our single market," she said.

In response to the pandemic, European Union governments have taken a further step towards economic and financial integration by agreeing to borrow money together for the €807 billion Next Generation EU recovery fund, which aims to support the post-pandemic recovery by financing projects that fight climate change and increase use of digital technology.

Irish Finance Minister Paschal Donohoe, who heads the Eurogroup panel of finance ministers from the member countries, said that the currency “has strengthened its foundations over the last 20 years. It’s proven its mettle in dealing with great challenges and great crises”.

Did the euro really drive up prices?

But some Europeans still blame the single currency for covertly driving up consumer prices, despite plenty of evidence to the contrary.

"The euro is a catastrophe, it's catastrophic," says Maria Napolitano, 65, an Italian living in Frankfurt.

"With 100 deutschmarks, you could fill up your shopping trolley. Now, €100 aren't enough to fill two bags."

This view is shared by many across the eurozone, with Victor Irun, 53, a teacher in Madrid, saying that for Spaniards the switch to the euro was "like entering a club for rich people while not wearing the right clothes".

"You had the impression we weren't yet ready," he said. "It was as if we were living in Spain, but paying with French or Dutch money."

However, a number of studies have indicated that the perceived inflation was not a reality.

Pierre Jaillet, a researcher at the Jacques Delors and Iris institutes in France, said that consumers' profiles played a significant role in whether they felt a discrepancy between real and perceived price developments.

"The average consumer price inflation basket corresponds to the average budget of an average urban white-collar worker," Mr Jaillet said.

People who are less well-off tend to spend a greater proportion of their income on food, so they will be squeezed more, he said, noting that consumers generally remembered price increases, but not price reductions.

Redesign of the banknote now in the works

As the currency’s notes and coins enter their third decade, the ECB is planning a redesign, with a final decision on the new look expected in 2024.

The banknotes' original designs, which featured generic windows, doorways and bridges from various eras that did not represent any specific place or monument, have undergone one relatively minor update since introduction.

However, the Austrian artist behind the original banknotes fears the revamp could spark national rivalries, something he painstakingly tried to avoid with neutral illustrations the first time around.

Now retired, Robert Kalina was working as a graphic designer for the Austrian National Bank when he won a competition in 1996 to create the artwork for the first euro notes.

"It's incredible to think that the euro is already 20 years old, I hope it stays around for a long time to come," he said.

The ECB is now also considering a digital euro, in step with other central banks around the world,

Ms Lagarde said recently that euro banknotes are "here to stay", with the ECB "the custodian of the euro" still working tirelessly to protect the single currency.

"It it our job to keep them secure," she said.