A 40-year project involving 300 scientists trying to generate high fusion power has ended with a record, consistently producing energy for a five-second blast.

While on the surface that may appear an exceedingly short time, it was enough time to smash the previous record and create 69 megajoules of energy using a mere 0.2mg of fuel.

That is enough to – briefly – power around 41,000 homes. Any longer than that would cause the machine's copper wire magnets to overheat.

The results were announced by the UK Atomic Energy Authority.

The previous record of 59 megajoules was set in 2022 by the same team at the JET project based at Oxford, using one of the world’s largest and most powerful fusion machines.

Nuclear fusion is the same process that the Sun uses to generate heat. Proponents believe it could one day help tackle climate change by providing an abundant, safe and clean source of energy.

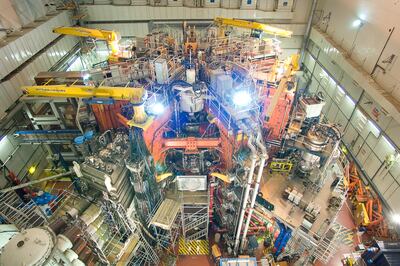

It was the final experiment to be conducted at the JET site using a doughnut-shaped machine called a tokamak.

“JET has operated as close to power plant conditions as is possible with today's facilities, and its legacy will be pervasive in all future power plants,” said UKAEA chief executive Ian Chapman.

He said the findings have critical implications not only for ITER – a fusion research mega-project being built in southern France – but also for other global fusion projects, pursuing a future of safe, low-carbon, and sustainable energy.

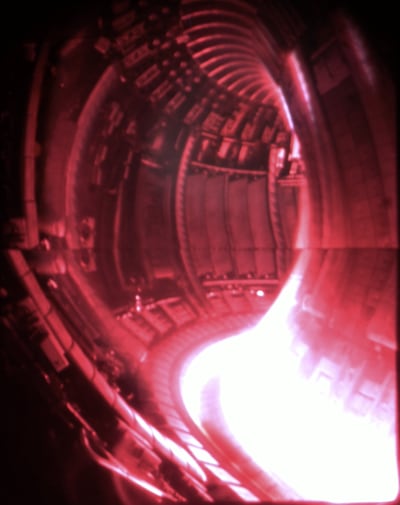

Inside JET's tokamak, 0.1mg each of deuterium and tritium – both isotopes of hydrogen – were heated to temperatures 10 times hotter than the centre of the Sun to create plasma.

This mixture was held in place using magnets as it spun around, fusing and releasing tremendous energy as heat.

Fusion is inherently safe in that it cannot start a runaway process.

Deuterium is freely available in seawater, while tritium can be harvested as a by-product of nuclear fission.

Using equivalent weights, it releases nearly four million times more energy than burning coal, oil or gas, and the only waste product is helium.

Despite the record, JET did not generate more energy than was put into producing it.

The Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in California became the only facility to achieve this feat – the holy grail of nuclear fusion – in late 2022, using a different process involving lasers.

JET conducted its first deuterium-tritium experiments in 1997.

More than 300 scientists and engineers from EUROfusion, a consortium of researchers across Europe, contributed to JET's landmark experiments over 40 years.

ITER will be equipped with superconductor electromagnets which will allow the process to continue for longer, hopefully longer than 300 seconds.

If all goes well at ITER, a prototype fusion power plant could be ready by 2050.

International co-operation on fusion energy has historically been close because, unlike the nuclear fission used in atomic power plants, the technology cannot be weaponised.

The France-based megaproject also involves China, the EU, India, Japan, South Korea, Russia and the US.

Prof Ambrogio Fasoli, programme manager at EUROfusion, said the demonstration of operational scenarios for future fusion machines instilled greater confidence in the development of fusion energy.

“Beyond setting a record, we achieved things we’ve never done before and deepened our understanding of fusion physics,” he said.

UK Minister for Nuclear and Networks Andrew Bowie said: “JET’s final fusion experiment is a fitting swansong after all the groundbreaking work that has gone into the project since 1983. We are closer to fusion energy than ever before thanks to the international team of scientists and engineers in Oxfordshire.”

The UK's Fusion Futures government programme has committed £650 million to invest in research and facilities.

JET concluded its scientific operations at the end of December 2023.