Hans Blix, Clare Short and Tony Benn may be names from the past for many people in Britain but the wider world has not moved on from the war they tried to prevent in Iraq, says the filmmaker Amir Amirani, and neither has he.

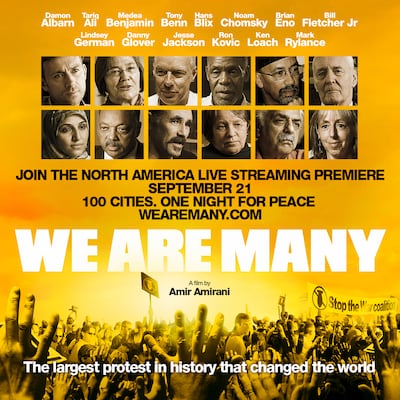

After spending nine years interviewing such people for his film We Are Many, about the global anti-war marches on February 15, 2003, Amirani is still engrossed in the topic: working on a release in America, thinking of writing a book, and developing an offshoot project he is keeping under wraps for now.

Since We Are Many was released in 2015, some of its central themes – truth and lies in politics, the way the public can be swept into military fervour – have only become more topical.

As the 20th anniversary arrives, Amirani will be curious to hear what public figures in Britain and the US have to say about the war, which he believes has been too easily chalked up as “a mistake” and put aside.

“I think the shadow of Iraq is going to hang over many things in this country for generations,” Amirani, who was born in Iran and moved to Britain as a child, told The National.

The fact that Britain went to war without UN backing “has been erased over here, but it’s not erased in the rest of the world, it’s not erased in other people’s minds,” he said. “These things have a habit of coming back and biting us.”

Amirani, in Berlin for a film festival in February 2003, joined a demonstration there that he said was the largest he has ever been on, despite the cold February weather on the big day.

But it was once he returned to London, and heard tales of how the protests had brought together the most unlikely people in an impassioned plea for peace, that he realised it was a phenomenon worth exploring as a filmmaker.

What other documentary could bring together the spy author John Le Carre, who was on the London march, the tycoon Sir Richard Branson, who tried to broker peace, and the weapons inspector Hans Blix, so central to the diplomatic crisis?

All appear in We Are Many along with more than 50 others interviewed during nine years of filming, including British protest organisers and American personnel who came to regret their role in the war.

Le Carre was a particular catch because he had previously said he would never give another interview and took some time to be brought on board.

In the film, Le Carre described a noise — “I have never heard before or since, a kind of visceral, feral grumble” — as the crowds passed Downing Street, pleading with Tony Blair, the prime minister at the time, not to go to war.

Also involved in London was the playwright Harold Pinter, who described Mr Blair as a “hired thug” of US President George W Bush. He died in 2008 and is the one person Amirani wishes he could have added to his interview list.

Organisers put the crowds in London at two million, and estimates of the global mobilisation range between six and 30 million, in one of the biggest single protest actions in human history.

The demonstrators may not have stopped the invasion, but Amirani believes that this failure made the protests more of a watershed rather than less.

“I think right up to that point, most members of the public still had a faith in politics, that their voices mattered. They did think that if they came out and protested, that politicians would take notice,” he said.

“We’re still living with the consequences of the fact that the public was so shocked by the way the scale of that protest was ignored.

“I think that was really the beginnings of a major rupture in trust between the public and politicians, in a way that had not been seen so visibly, so brutally and so plainly.”

Iraq War protests in London in 2003 - in pictures

The British and American case for war was based on claims that Saddam Hussein’s Iraq was developing weapons of mass destruction, which turned out not to exist.

The invasion went ahead without the support of the UN Security Council after Russia, France and China failed to side with their fellow permanent members, the US and Britain.

Mr Blair has since argued that the world was still better off without Saddam, and insisted the flawed intelligence was an honest mistake rather than an act of deception.

Amirani, meanwhile, says a “post-truth” or “post-shame” political culture often talked about during Donald Trump’s US presidency can be traced back further to Mr Blair's slick spin operation.

The claim, in a dossier published by the British government in 2002, that Saddam could have deployed chemical or biological WMDs within 45 minutes of an order to do so came to symbolise the loss of public trust in Mr Blair.

“There was something very shameless about that Iraq War debacle, and everything that’s followed since,” Amirani said. “The shamelessness of Boris Johnson and the shamelessness of Trump, the shamelessness of politics.”

Another consequence in the aftermath was that Britain became warier of putting “boots on the ground” abroad. When MPs voted against military action in Syria in 2013, the shadow of Iraq hung unmistakably over the debate.

Now, as Britain arms Ukraine without directly entering a war with Russia, Amirani believes that the UK’s moral standing on the conflict is undermined by what happened in Iraq, even 20 years later.

“It’s funny how everyone is all-out gung-ho attacking Russia, including the UK, which perpetrated a war in Iraq without UN backing, essentially with no legal basis at all. That part of memory has been completely erased,” he said.

Despite all these developments since the war in 2003 and the film’s release in 2015, Amirani considers We Are Many to be an evergreen film about protest and war.

He also cannot be, he thinks, the only protester for whom February 15, 2003, was a defining moment in their lives, mentioning activists who were subsequently inspired to campaign for causes such as peace, democracy and Black Lives Matter.

“It sticks in people’s memories because of the scale of it, because of what it represented politically at the time. For lots of young people, it was foundational,” he said.

“That protest, the size of it, was such a sea change. It had ripple effects, culturally, socially, politically, for lots and lots of people.”