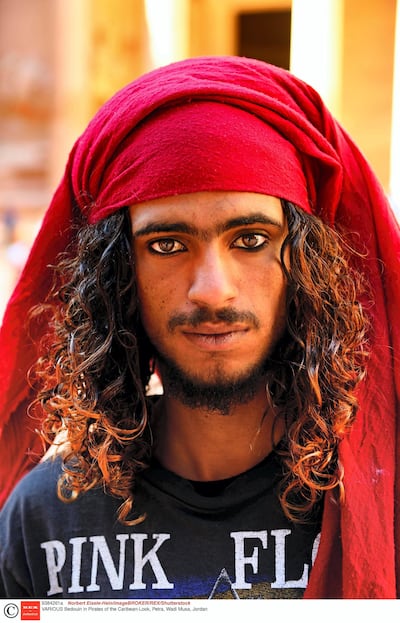

With his dark kohl-rimmed eyes, chiselled cheekbones and wild hair bound by a black headscarf, it’s easy to see why women fall for Ahmed Alfaqeer.

The look, which resembles Johnny Depp's character in Pirates of the Caribbean, is popular among young men in Petra, who tell tourists that the actor copied them.

But Mr Alfaqeer’s picture, featured on a Facebook group set up to avenge jilted lovers, comes with a warning to female tourists visiting Jordan’s most famous attraction: steer clear of this man and others like him out to seduce foreigners for financial gain.

“When a beautiful tourist girl walked by in Petra they were like tigers — who could lay her down fastest and who could get her fooled into believing their lines,” said Mary Smith, who runs a Facebook group called Stop the Petra Bedouin Women Scammers.

Tourists travel to Petra dreaming of adventure in the hidden desert city, which provided the backdrop for Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade. But for some women who believe they have found love in this magical setting, the mirage dissolves into a nightmare, leaving them broken-hearted or, at worst, victims of violence, blackmail and sexual assault.

Tales of heartbreak

Between five and 10 victims contact Ms Smith each week via Facebook, she says, which is one of several social media platforms set up to expose fraudulent love affairs in Petra, even before the #MeToo movement became an international phenomenon.

Story after story fills these feeds, cataloguing the hurt and humiliation of women who have handed over hundreds or even thousands of dollars, only to realise the romance was a sham.

“Girls have been trying for more than 10 years to warn others on tourist sites like TripAdvisor and Visit Jordan but every time they commented on the problems their posts were deleted,” said Ms Smith, who estimates that about 50 men operate around Petra and a further 10 in nearby Wadi Rum — another big stop on the Jordan tourist trail.

“The government, the Jordanian people, the tourist police, the travel companies — everyone knows about the scamming — but Petra is one of the new seven wonders of the world and that means tourists and money,” she said.

Romantic setting

Carved from rocks that glow burnt pink at sunset — the poet John William Burgon famously described it as a “rose-red city half as old as time” — Petra is a fairy tale setting and female tourists frequently find themselves wooed by unbridled flattery followed by invitations to dine in candlelit caves under star-studded desert skies.

Some decide to stay on, putting their lives at home on hold to spend more time with their Bedouin boyfriends.

Daily Skype calls maintain contact when they part and promises of marriage are often quick to follow. Only later do the sob stories of sick relatives and dead donkeys start, accompanied by requests to borrow money.

One woman was asked to lend her boyfriend’s acquaintance US $5,000 to fund his election campaign.

Maria, a European woman in her thirties, knew nothing of this when she visited Petra in July last year. Like many of the victims, she still fears repercussions from her lover and prefers to use a pseudonym.

Five days after arriving to start a new job in Jordan’s capital Amman, she took the three-hour bus down to Petra, eager to see the storied caves and carved temples, which date back to the fourth century BCE.

Winding through the narrow gorge that marks the spectacular entrance to the ancient site, she tried to sidestep the group of young men idling on a ledge calling out offers of free tours.

“I said no until I was so tired and they were so funny, that finally I allowed one of them to accompany me,” she said.

That was the first time she met Mr Alfaqeer, a Bedouin man in his twenties. The tour led to a coffee and then dinner, where he bought her “beer after beer.” They spent the night together and she stayed with him for the next two days, during which he was “sweet, lovely, generous and solicitous”.

He gave her a piece of kohl and entranced her with tales of his childhood in the desert.

She was drawn by the freedom he embodied and the warm welcome from his friends, who seemed to Maria like “authentic people from an ancient population”.

For the next three weeks she visited every weekend and was introduced to Mr Alfaqeer’s family as his girlfriend, or sometimes his wife. “I found that really weird but thought it was due to his culture,” Maria said.

He pointed out other western women living in his village and told her about New Zealander Marguerite van Geldermalsen, who moved to Petra in the late 1970s and later wrote a book, Married to a Bedouin, which is still sold around the site.

When they weren’t together, Mr Alfaqeer bombarded her with calls, asking jealously about her male friends.

But he was also caring, showering her with affection and pulling her heartstrings with tales of family poverty, made worse by fewer tourists during the summer.

When he asked for JD1,000 (Dh5,173) she was dubious but eventually lent him JD400, followed by a further JD600 when her wages came through. Over the course of their relationship she says she lent him at least JD1,850.

“He kept insisting he would pay it back after he started working. I finally believed him because he was sweet and persistent and I had feelings for him,” she said.

Legal recourse

Lawyer Emad Hammudi has acted for four women seeking redress against men in Petra. Most of these cases are about retrieving the money they have lent, or in some instances sexual harassment.

“It’s all about manipulating your thoughts, your feelings,” he said, explaining that the men are practised seducers. “She becomes blind with his love, he treats her like a princess and after he gets her money, he disappears.”

Taking the men to court is difficult and women are often unwilling or afraid to remain in Jordan long enough to see the trial through, he said.

The seducers sometimes juggle several romances, cultivating continuing relationships overseas while targeting new women coming to the site, even reportedly keeping journals on their victims to better understand how to manipulate and exploit them.

Some women also cite more serious allegations against the men, including sexual assault and rape. However, these are difficult to substantiate and the charges are often dropped, or fail to result in conviction due to lack of evidence.

For Maria, the relationship quickly soured. After handing over the rest of the money, Mr Alfaqeer’s behaviour changed and he became increasingly possessive, hurling insults at her if she spoke to his male relatives or spent more than a few minutes out of his sight.

He forced her to share the passwords for her phone and social media accounts, copying her contact list and turned violent when she tried to refuse, she said.

Trapped and frightened, Maria called the police but the violence quickly led to blackmail. “It was then that he showed me the erotic photos I once sent him,” she said.

“Every moment after that he threatened to send them to my son and family.”

At this point, Maria says she went to the police.

Maria provided officers with Western Union receipts for money transfers as well as audio recordings and photo evidence of the blackmail she described.

“The police believed me,” she said, but the proof wasn’t enough to secure a conviction. Mr Alfaqeer spent a week in jail before being released.

__________

Read more:

Jordan warns of 'serious consequences' of revoking Palestinian refugee status

Jordan lobbying for Palestinian statehood as US finalises peace plan

General strike brings Jordan to a standstill

__________

The police in Petra are aware of the problem but insist incidents are rare. Tourists sometimes have “relationships with people who live inside but to take money from them no — they are not blackmailing them,” said Captain Talal of the Petra Tourism Police.

“If there's any problem we can deal with it but in general not many cases happen inside Petra.”

Local authorities say there are “severe consequences” for perpetrators if criminal activity can be proved. “We try our best to limit it,” said Mahmoud Freihat, area marketing manager at the Jordan Tourism Board. “But the implementation of the law can get quite tricky, how can you prove it?”

Many locals are critical of the practice, which threatens Petra’s ailing tourism industry and contradicts the Muslim values that bind the local conservative community.

"Nobody likes it, it's really not nice," said Eid Al Hasanat, who runs a guesthouse in Wadi Musa. "It reflects badly on the whole community."

Charlotte, a woman in her 40s who visited Jordan in 2015 to study Arabic, finds it painful to recall her encounter with Rashid, a “much younger” Bedouin man.

After moving into his house she was soon put under pressure to buy him a mobile phone and hand over money — $50 at first — followed by larger sums.

Western Union receipts show she transferred $567 in October 2016 and €215 a month later.

Both Mr Alfaqeer and Rashid denied taking part in the romance scams. Rashid told The National he'd had relationships with three foreign women but insisted he didn't ask for money.

Charlotte remembers watching him get ready to take another tourist — a younger Australian girl — on a private tour.

When he didn’t return that evening she left but he continued to hound her for money, sending messages that were insulting, pleading and affectionate in turn.

In an email to Rashid last October, Charlotte replied: “You hit me, spit on me, insulted me, lied to me, cheated on me. Now, finally, I know that you never had love for me.

“I admit I was a fool, but I was in love.”